Fruit growers had a lot to learn during day two of the 2019 Great Lakes Fruit, Vegetable & Farm Market EXPO in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

During an apple session, Norman Lalancette, an extension specialist with Rutgers University, discussed what he called the “big three” fruit rots: bitter rot, white rot, and black rot. Following are some of the points he made:

—The bitter rot pathogen overwinters in buds, mummies, cankers and dead wood.

—Fruit is susceptible all season; infection is most common mid- to late-season.

—White rot: Early fruit lesions are small, circular brown to tan spots.

—Most early lesions latent until two to four weeks before harvest. As lesions expand, rotted area expands to the core as a cylinder.

—If above 75 degrees Fahrenheit, rotted fruit is clear tan to light brown, soft and watery. If cooler, lesions are firm and deeper tan.

—Infections begin at lenticels or wounds; lesions sunken red-brown. Blisters form, rupture, exude liquid.

—Overwinters as mycelium, pycnidia and pseudothecia in cankers, bark and mummies.

—There are many pathogen hosts in forest and landscape trees.

—Fruit infection through lenticels, wounds or directly.

—Twig/limb infection through lenticels; associated with hot, dry summer weather; moisture stress following infection is necessary.

—Black rot: Causal organism is Botryosphaeria obtusa.

—Overwintering inoculum in cankers, mummies, dead wood and fire blight strikes. Foliar infection begins at bud break; fruit infected soon after petal fall; inoculum available all summer.

—Cultural controls: plant cultivars less susceptible to fruit rots; none are immune, so all need additional controls.

—Irrigate during hot, dry periods (especially for white rot).

—Fungicide controls: Manzate works well against bitter rot and white rot; Captan works well against black rot.

—Merivon works well against bitter rot.

Hemant Gohil, an agricultural agent with Rutgers University, discussed new peach and nectarine varieties from the Rutgers Tree Fruit Breeding program.

The germplasm used for developing these New Jersey varieties was sourced from different parts of the world. Plants were selected for vigor, tolerance to environmental stress, and fruit characteristics, with the potential to increase consumer demand, according to Gohil.

Five varieties were released in 2017, after multiyear evaluations and research at locations throughout New Jersey, each representing a different microclimate. Gohil shared some of their characteristics:

Evelynn (NJ 357) – A yellow-fleshed peach with semifree stone and firm flesh. A low-acid peach that ripens with Redhaven.

Selena (NJ 358) – A late-season yellow peach with excellent firmness. Large-fruited, with attractive 50- to 80-percent red-on-yellow background.

Tiana (NJ 359) – A late-season yellow peach with free stone and very firm flesh. Large fruits have an excellent balance of acidity and sweetness.

Brigantine (NJN 102) – A yellow-fleshed nectarine with semifree stone. It has a solid scarlet coloring and a nice acidic flavor and firm melting flesh.

Silverglo (NJN 103) – A white-fleshed nectarine with a cling stone/semifree stone. It has a nice acidic flavor, attractive color and very few skin blemishes.

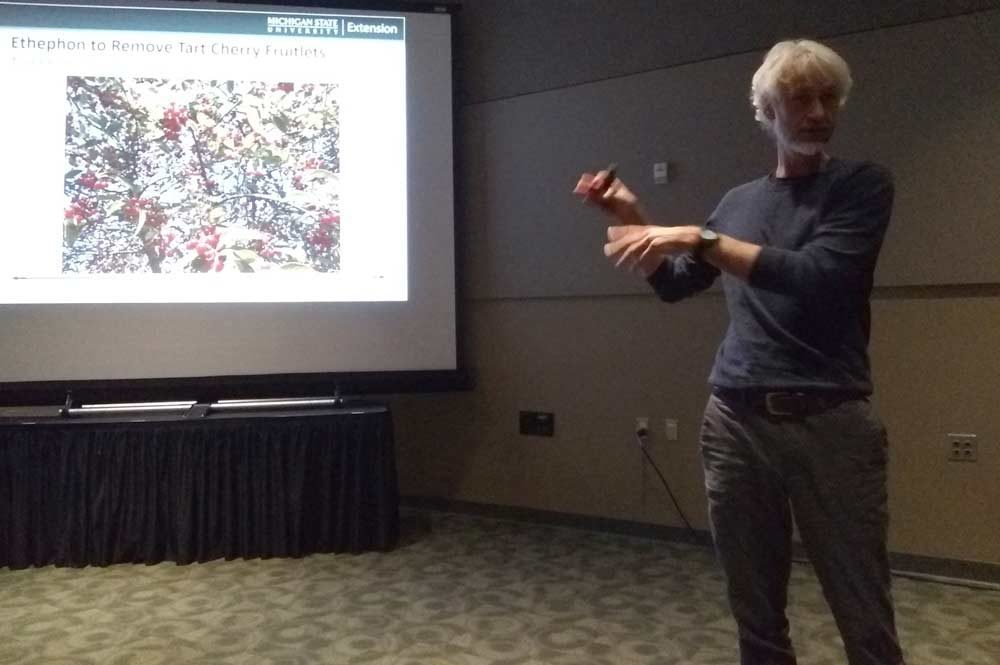

During a tart cherry session, Todd Einhorn, an associate professor at Michigan State University, discussed using the plant growth regulator Ethephon for fruit removal.

Einhorn and his team applied Ethephon to whole trees at MSU research stations in Traverse City and Clarksville, and also at commercial farms. Here’s a couple of his findings:

—Preliminary findings in 2017 found that Ethephon reduced fruit set by 65 percent at full bloom, but not at shuck split. Einhorn wondered if there was a developmental period at which cherry is more susceptible to Ethephon applications.

—If temperatures are below 80 degrees, you need high rates of Ethephon to stimulate abscission. Ethylene production is very dependent on rate and timing.

—by Matt Milkovich

Leave A Comment