—by Nataliya Shcherbatyuk, Pierre Davadant and Melissa Hansen

Vineyard nutrient management often focuses on nutrient inputs that fertilizers, compost and cover crops add to a vineyard. But a recent discovery by Washington State University scientists puts new light on nutrient outputs.

Research found that nutrient outputs lost from harvested grapes and senescent leaves may be more significant than previously thought and should be considered in vineyard nutrition plans.

On average, more than 70 pounds in total of nitrogen, potassium, phosphorus and magnesium per acre were lost annually between harvest and leaf fall during the course of a four-year study. Of particular interest to Washington wine grape growers, who often experience frost events before harvest is over, is the discovery that the loss of nutrients from leaf fall was even more pronounced when leaves were killed quickly by early frost rather than through normal senescence.

Vineyard nutrition is about balance. Nutrients have specific roles for different physiological processes, and vineyard managers must regulate the supply of macro- and micro-nutrients for optimal growth, fruit development and overall vine health. Both nutrient inputs and outputs must be considered to avoid development of nutrient deficiencies. If nutrients aren’t adequately replaced, the resulting imbalances can lead to reduced yield, delayed fruit maturity and compromised fruit quality.

Nutrient inputs come from fertilizer applications, nitrogen fixation by legume cover crops and some deposition from rainfall. Nutrient outputs are the losses of nutrients through harvest and leaf fall, as well as leaching and denitrification. Growers commonly use lab analysis of grapevine tissue (leaf blades and petioles) and soil samples to help them assess the nutrient status of their vineyard and guide the development of a nutrition plan. A key step in creating a vineyard nutrition plan is to consider not only the nutrients that were added but also those that were removed at the end of the growing season.

Nutrient output study

Research to assess nutrient loss at the end of the growing season from harvested fruit and leaf fall was conducted by a team of WSU scientists led by Markus Keller, Chateau Ste. Michelle Distinguished Professor in Viticulture. Although nutrient inputs have been well studied, there is little information about nutrient loss from harvested wine grapes — and even less on nutrient loss from leaf fall. The study was funded through state and federal specialty crop research grants, with support from the Washington wine industry and the Washington State Wine Commission.

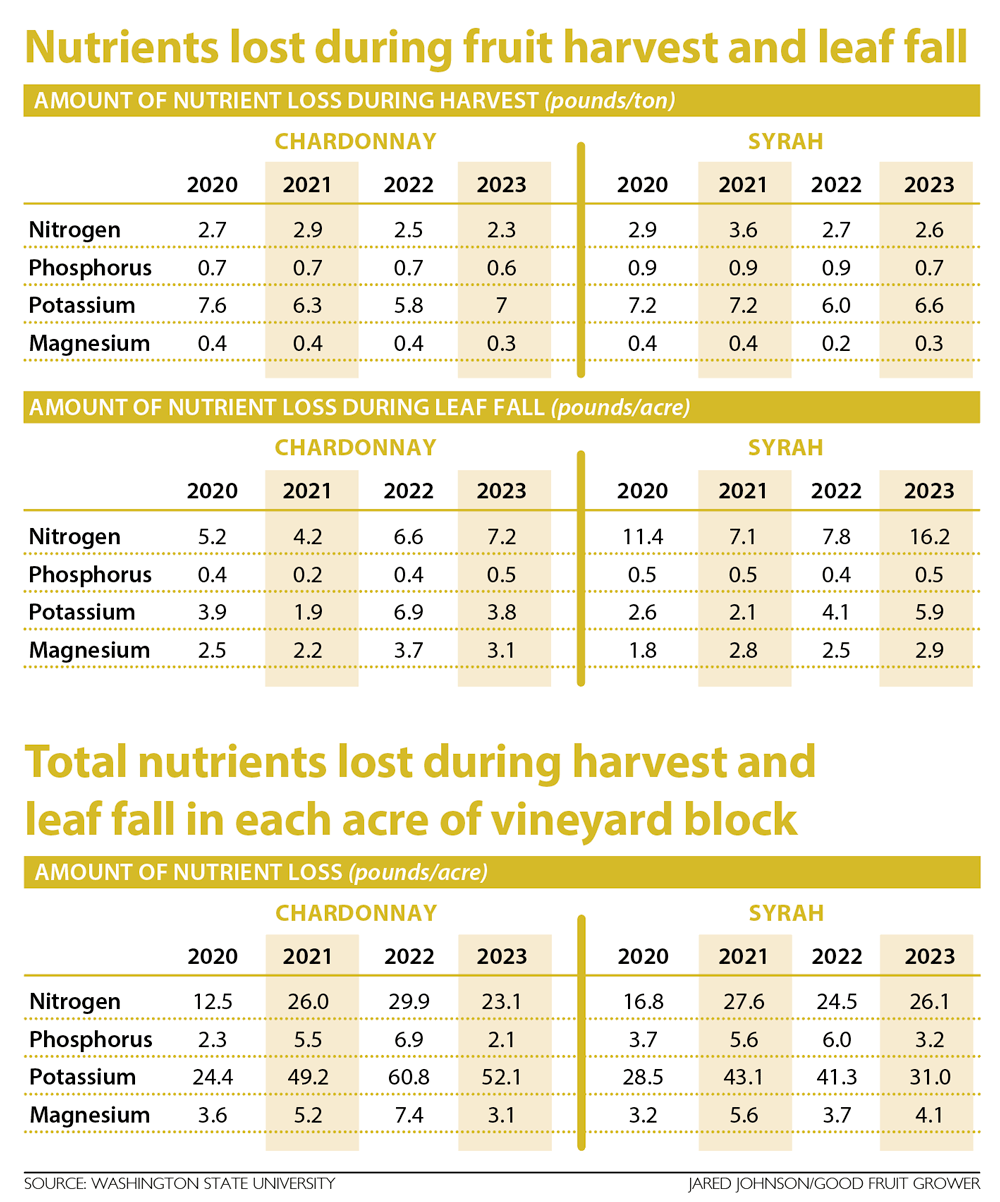

The vineyard trial took place in a commercial vineyard located in the Horse Heaven Hills American Viticultural Area in Paterson, Washington. Harvested fruit and leaves of own-rooted Chardonnay (planted in 2010) and Syrah (planted in 1998) grapevines were analyzed for four years, from 2020 through 2023. Samples were tested for nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium and magnesium. Random samples of fruit from a 1-acre block within the large commercial vineyard were collected, dried, ground and sent to a commercial laboratory for nutrient analysis. Random vines within the block were also netted after harvest to capture leaves. After the first killing frost, which is below 28 degrees Fahrenheit, the leaves were analyzed for the same four macronutrients as was the harvested fruit.

Growing conditions and yield varied among cultivars and years in the trial. Yield, on average, was 6.6 tons per acre for Chardonnay and 4.8 tons per acre for Syrah. The average growing degree-day (GDD) accumulation for the four years was 3,433, with the lowest GDD occurring in 2022.

Losses from harvest and leaves

Nitrogen removed during harvest averaged 2.8 pounds per ton for the four seasons. While that amount sounds small when considering the volume of grapes, when calculated on a per-acre basis this equaled an average of 23.3 pounds of nitrogen per acre that was removed annually. Per-acre losses from other nutrients included an average of 4.4 pounds of phosphorus, 41.3 pounds of potassium and 4.5 pounds of magnesium.

A key focus of the research was to better understand nutrient loss from leaf fall. Senescence, the final stage of plant development, when leaves age and fall off, is crucial to future growth. As the leaves age, key nutrients are remobilized to storage organs for use in the next growing season. The WSU research team sought to assess the nutrient loss from leaves and to determine if there is an impact when leaves are killed by an early frost. The vintages of 2020, 2022 and 2023 were marked by fall frosts occurring on Oct. 23, Nov. 10 and Nov. 9, respectively. In 2021, the first frost occurred on Dec. 9.

The nutrient losses from leaves showed more seasonal and cultural variation than the losses from harvested fruit. Nutrient losses from grapevine leaves were generally higher in growing seasons when leaves were still green at the first killing frost. The exception was phosphorus, which showed no impact from the timing of frost. Chardonnay averaged a leaf-fall loss of 5.8 pounds of nitrogen per acre; Syrah averaged a nitrogen loss of 10.6 pounds per acre.

Leaf potassium was most responsive to seasonal differences and was much lower after the long fall of 2021 but was higher in Chardonnay in 2022 and Syrah in 2023 when frost killed green leaves.

Obviously, a grapevine that goes through an early killing frost — below 28 degrees, which kills leaves before their nutrients have had time to relocate to other parts of the grapevine — will potentially have lower stored nutrients available to support growth in the spring. Additionally, if the senescent leaves are blown out of the vineyard by wind, nutrient recycling in the soil is prevented and a significant amount of nutrients could be lost.

Key findings

Key findings from this study include:

—Nutrient losses from harvest and leaf fall were significant and should be accounted for when developing a vineyard nutrition plan for the coming season.

—Nutrient losses from leaves were greater when the vineyard experienced an early killing frost while leaves were still green.

Growers can use this new information as a reference to balance their vineyard nutrient inputs and outputs, considering their specific vineyard characteristics, local weather and yields. An alternative or supplemental approach to sampling grapevine tissues at bloom or veraison could be sampling fruit at harvest and leaves at leaf fall.

Knowledge of the nutrient output information could help with estimation of vineyard nutrition needs for the coming season. Remember to consider both the nutrient inputs and outputs to maintain vineyard nutrition balance and keep your vineyard healthy. This is especially important in dry regions, such as Eastern Washington, where soils have low organic matter, the natural nutrient content of soil is relatively low, and vine growth and productivity rely on irrigation and nutrient inputs. •

Nataliya Shcherbatyuk is a postdoctoral scientist and Pierre Davadant is a graduate student, both working under the direction of Markus Keller, a professor in the Washington State University Department of Viticulture and Enology. Shcherbatyuk also serves as the project manager for the High-Resolution Vineyard Nutrient Management grant funded by the USDA-National Institute of Food and Agriculture’s Specialty Crop Research Initiative. Melissa Hansen is the research program director for the Washington State Wine Commission.

Leave A Comment