—by Michelle Cook and Evan Esch of the the Okanagan-Kootenay Sterile Insect Release Board

The Okanagan-Kootenay Sterile Insect Release (OKSIR) Board gets a lot of questions about the unique Canadian program for codling moth control taking place just north of the Washington border. Growers, scientists and governments from around the world often want to know how the program works and if sterile codling moth releases could be used effectively in their apple regions. Here are some answers to the questions we are most frequently asked.

What is the Okanagan-Kootenay Sterile Insect Release Board?

The OKSIR Board is a local government agricultural program that works toward reducing wild codling moth populations in the Southern Interior of British Columbia, Canada. The OKSIR Program provides a number of codling moth services to apple and pear growers, including sterile insect releases (SIR), monitoring, crop consulting, and even enforcing the removal of abandoned orchards or infested backyard trees. The board is funded partly by local growers, who pay a tax based on the number of acres of apples and pears they grow, and partly by local area residents through their municipal property taxes.

How does sterile insect release work?

SIR works by intercepting the mating of wild codling moths. The trick is to rear and release moths that are “sterile, but still sexy,” Michelle likes to say. Codling moths are produced in a state-of-the-art mass-rearing facility in Osoyoos, British Columbia. Moths are sterilized with a precise dose of gamma radiation before being released into orchards. When sterile moths mate with wild moths, they break the life cycle of the pest and prevent crop losses.

In the end, it becomes a numbers game. The more sterile insects we release, the less likely a wild male and wild female will successfully mate amongst the flood of our sterile moths. On the other hand, if the wild population is very large, it is hard to outnumber the wild moths with sterile moths, and the chance of wild moths successfully mating increases.

How do Canadian growers use SIR in their integrated pest management (IPM) practices?

In British Columbia, SIR is the foundation of codling moth IPM. All orchards receive a base number of sterile moths per acre delivered by OKSIR staff. The base rate is 800 insects per acre, released weekly throughout the 22-week season. Orchards with higher wild codling moth populations get higher release rates of sterile moths, which are two to four times the base rate. OKSIR staff estimate that 70 to 80 percent of British Columbia growers do not spray at all to specifically control codling moth. Here, SIR alone can keep damage below commercially acceptable levels (0.2 percent infested fruit, or less) in 90 percent of the region’s orchards.

Mating disruption, sprays and orchard sanitation are additional IPM tools that Canadian growers use on top of sterile codling moths to bring down wild codling moth populations when damage is seen. When orchards are battling codling moth infestations, they do use all of the other tools at their disposal. It can take two to three years of using sprays, SIR and mating disruption to bring high codling moth damage back down to the levels we want them, and even longer for organic orchards.

If the sterile insect program is 30 years old, why is it that it is only recently appearing in the Pacific Northwest?

Over the past 30 years, many orchards in British Columbia have transitioned from apples to cherries and grapes. This has recently created surplus production capacity at the OKSIR rearing facility and, with the help of M3 Agriculture, we are now able to supply moths to a portion of the Pacific Northwest’s orchards.

Are SIR and mating disruption compatible?

Peer-reviewed research has shown that SIR and mating disruption are compatible and complementary. Both tools prevent wild moth mating, but in different ways. Both of these tools are very effective at suppressing low to moderate populations, and they both need to be supported with sprays, sanitation and good horticultural practices to control more serious infestations, Evan said. Like programs based on mating disruption, SIR-treated blocks are vulnerable to mated female moths moving in from the outside. Damage can occur on orchard perimeters, even if these tools are working as expected.

Does SIR need to be applied areawide to work?

No, because mating disruption is essentially applied areawide in Washington orchards, SIR can be applied as an additional tool on top of the existing IPM tools already being used.

Many growers in British Columbia don’t spray for codling moth. Is SIR the silver bullet?

No, SIR is not a silver bullet!

Managing grower expectations has been a major challenge since we started providing sterile insects to Washington through M3 Agriculture. We try to steer people away from the mindset of “DoesSIR work or not?” We’ve been using SIR for 30 years in Canada. We know the insects are sterile. We know the technique works. The question for growers in the Pacific Northwest is: “Where will SIR fit best into my existing IPM plan?”

Since outnumbering the wild population with sterile moths is key for SIR to work, you cannot add SIR to a very badly infested orchard and expect to see the problem clean up immediately. SIR will help drive down the wild population with each generation, becoming more effective as the population declines. In reality, it’s going to take two to three years of SIR to get a bad infestation under control, when combined with other tools like sprays, mating disruption and sanitation. We see this happen all the time for our growers as well.

We hear from some Washington growers who have had success targeting “medium” infestations with SIR, and they are getting really good results. We’ve all been in a badly infested block before and understand that it takes lots of time and money to get those blocks back to being profitable again. SIR is a good tool to use before things get that bad.

Do I need to change any other farming practices while using SIR?

During release, some sterile moths will end up on the orchard floor. Avoid watering and mowing on moth release days. This will give the sterile moths the best chance of surviving before they “wake up” and move into the canopy.

Pheromone traps will collect sterile and wild moths alike. Sterile moths are fed an internal, red marker at the rearing facility. Squishing the moths on the trap card will reveal the red marker in the sterile moths. It is easy to tell sterile from wild moth guts with just a little practice.

The sterile females also produce pheromone, which can reduce the efficiency of your traps. Think of the sterile females as an additional 400 “little, mobile mating disruptors” per acre. This means that wild captures will drop immediately after SIR is introduced to an orchard, even before the sterile moths have had a chance to interfere with the wild mating. Be prepared to keep up with first generation sprays, and then review your wild captures and damage to determine how SIR will impact your traps moving forward.

The impact of sprays on sterile moths is not well studied. Most insecticides target larvae and eggs, not adult moths. There may be nonlethal effects of some conventional sprays on sterile moths, while organic sprays likely have no impact on sterile moths. In British Columbia, we do not see reductions in sterile recapture rates if/when sprays are used, and when growers need to spray, the majority of growers combine SIR with conventional insecticides.

How exactly would I apply SIR?

Because Washington and Oregon growers are using SIR within a different context of codling moth management than are British Columbia growers, it is hard for OKSIR staff to make prescriptions for its optimal use south of the border. Coming up with a regionally specific, trap-based moth threshold would be very useful. For now, growers will have to examine their wild captures and damage surveys year over year and consider where SIR can fit best.

As growers become more familiar with SIR, they will become more confident with how it works for them. It is not going to be the right fit for every orchard, but it can be an important tool to reduce codling moth populations and slow the development of pesticide and virus resistance.

Michelle Cook is the general manager at the Okanagan-Kootenay Sterile Insect Release Board, and Evan Esch is the entomologist for the program. They can be reached by email at mcook@oksir.org and eesch@oksir.org, respectively.

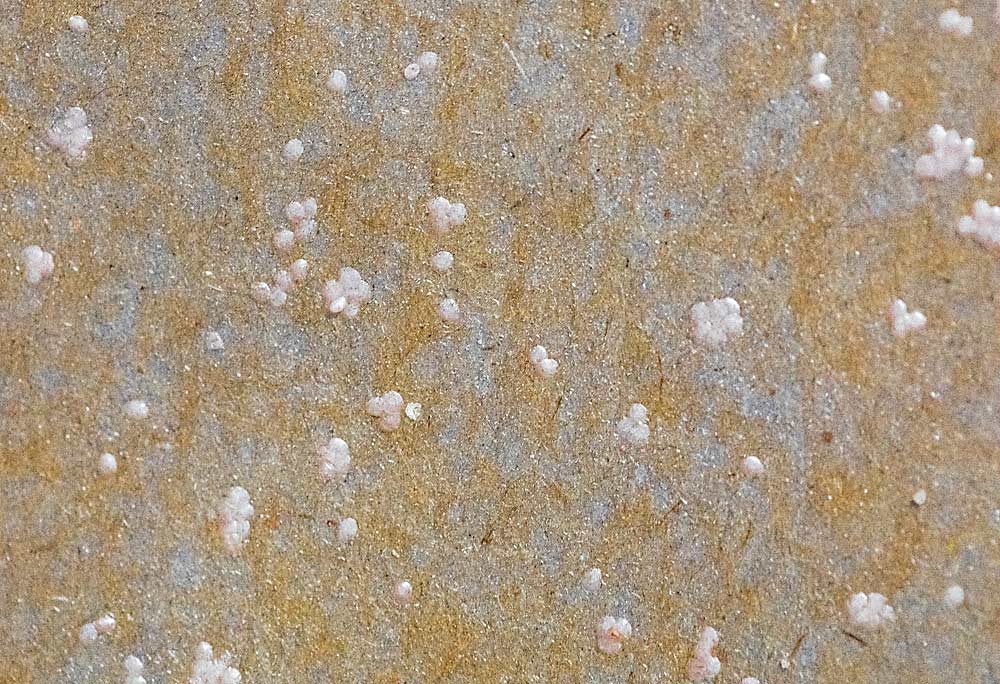

An inside look

The Okanagan-Kootenay Sterile Insect Release Program has been in operation in Osoyoos, British Columbia, since 1993. The $7.4 million facility rears millions of codling moths to control the population of wild codling moth in the Okanagan Valley. As apple and pear acreage in the region has been replanted to cherry orchards and wine grape vineyards over the past decade, the facility has excess capacity and has begun to supply interested growers in Washington and Oregon through a partnership with M3 Agriculture. The photos here provide an inside look at a few of the steps in the sterile moth rearing process, from Good Fruit Grower’s visit in 2018.

Leave A Comment