It is important to quickly prune out fire-blight-infected materials soon after an infection occurs, to reduce the bacterial ooze that insects and wind can spread through the orchard, causing new infections, and to reduce the spread of the pathogen through the tree, which can kill the tree. This article summarizes information from a new study.

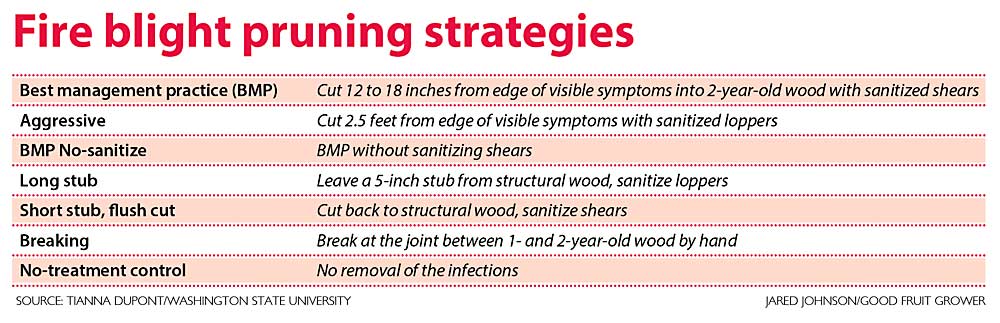

We conducted 10 experiments looking at the success of fire blight removal strategies in Washington, Oregon, Pennsylvania and New York. Experiments had different scions, rootstocks, vigor and training systems. We compared six therapeutic fire blight removal practices: cutting 12 to 18 inches from the edge of noticeable symptoms, with and without sanitized shears; cutting 30 inches; leaving a 5-inch stub on structural wood; cutting flush on structural wood; breaking the joint between 1- and 2-year-old wood; and a no-treatment control. Each treatment was replicated six to 15 times.

Which fire blight removal treatments save trees?

Timely summer cutting of fire blight infections can significantly reduce the number of trees that die from fire blight. In five of our experiments, trees died due to fire blight infections. In those experiments, all the pruning strategies reduced the number of trees that died. For example, in all four New York experiments, 100 percent of the trees receiving no pruning treatment died, while zero trees receiving a removal treatment died.

Which fire blight removal strategies reduce new symptoms after pruning?

When pruning blight, we are trying to cut far enough below noticeable symptoms so that the bacterial cells that remain in the plant are not sufficient to cause cankers to re-occur at the cutting point. We also want to prevent the bacteria from moving systemically through the vascular tissue and intercellular spaces in infected trees and causing new symptoms in young, tender shoot tips.

The standard best management practice (BMP) of cutting 12 to 18 inches from the edge of blight symptoms into 2-year-old wood, using sanitized loppers, generally reduced new symptoms from canker re-formation or the systemic movement of fire blight bacteria through the tree. BMP reduced new symptoms in seven of nine experiments, with significant differences in five of nine experiments. The exceptions were some experiments where no new symptoms occurred or where trees were very young and vigorous.

For example, in the 2020 Washington trial, the Cripps Pink trees were 14 years old and had low vigor, and no new symptoms were recorded. Similarly, in the 2020 Pennsylvania trial, the spring was very cool and was followed by hot temperatures and terminal bud set. In contrast, in the New York 2021 trial, trees were young (3 years old), vigorous NY 2 (the cultivar marketed as RubyFrost) and none of the treatments significantly reduced the number of new symptoms and cankers that re-formed after initial pruning.

Can aggressive cutting reduce new symptoms after pruning?

We hypothesized that aggressive removal, cutting 2.5 feet below blight symptoms, would remove more bacterial cells in symptomless wood and, consequently, reduce the number of new symptoms caused by systemic movement of bacteria to new, young, susceptible shoots. Generally, the aggressive treatment did not improve on BMP, where fire blight was removed 12 to 18 inches below noticeable blight symptoms, using sanitized loppers.

The exception was a Washington trial in 2019 with Yarlington Mill grafts. Even with aggressive removal in vigorous trees, multiple passes can be necessary to remove symptoms. For example, in the New York 2019 MAIA-1 (EverCrisp) trial with vigorous 4-year-old trees, both BMP and aggressive treatments reduced new blight symptoms threefold when compared to the no-treatment control but still resulted in four to five cankers per tree that re-formed after initial pruning.

Can a stub cut keep fire blight cankers from reaching structural wood?

When cankers caused by fire blight infections reach central leaders and main structural branches, growers face a difficult decision. Prune out the canker, and growers lose large parts of the tree and its productive capacity. Leave cankers in place, and those can become the source of new fire blight infections the following spring.

Some recommendations suggest an “ugly stub cut,” where growers make cuts leaving a 5-inch stub. While small cankers will form on many of these cuts, these cankers can be removed during winter pruning. In two of five experiments where long-stub (5-inch) and short-stub (zero to 2-inch) treatments were compared, a long stub reduced the number of cankers on structural wood. We saw significant reductions in the 2020 Washington trial on Cripps Pink. In trials where leaving a long stub was not helpful, no cankers formed on structural wood due to low susceptibility (e.g., old Red Delicious interstems) or terminal bud set right after infections occurred (2020 Pennsylvania).

Is breaking by hand as effective as removal with loppers?

In some orchards, managers employ the technique of breaking current-season growth rather than cutting to remove fire-blight-infected wood. This practice is designed to be quick and avoid the use of loppers. With this strategy, workers break branches at the joint between 1- and 2-year-old wood.

Breaking off diseased branches by hand provided a rapid removal method, but it can result in a greater number of cankers in the orchard at the end of the season, with more cankers on structural wood. In the Washington 2021 Cripps Pink experiment, where 4-year-old trees were trained to the wire, breaking resulted in significantly more re-formed cankers and new symptoms than other removal treatments, and it was similar to the no-treatment control. In three of 10 experiments, breaking resulted in significantly more canker tissue left in the tree at the end of the season, compared to BMP. A larger number of remaining cankers provide a greater source of inoculum in the following year.

Is it necessary to sanitize loppers when removing fire blight?

Sanitizing pruning shears has been long considered important to prevent dissemination of fire blight infections. However, in multiple prior studies, sanitizing shears made no difference in preventing new or re-formed canker development as long as cuts were made at the recommended distance below canker margins. This is likely because fire blight bacteria can quickly migrate — up to several meters — beyond the visible symptoms and, therefore, it makes little difference if a few bacteria are left on the cutting blade.

In our study, skipping sanitization when making the BMP cuts 12 to 18 inches beyond visible symptoms did not result in a significantly greater number of re-formed symptoms after initial cutting, when compared to BMP with sanitization, in nine of nine experiments. The quantity of canker left in the tree at the end of the season was also not different between BMP and BMP without sanitization. In one of seven experiments, BMP without sanitization had a greater (but not significantly different) number of trees develop rootstock blight.

Sanitizing pruning loppers may reduce transfer of bacteria if managers cut through active ooze. However, in situations where there are many infections throughout the block, the speed at which crews can remove blight is critical to reduce the number of trees that die due to systemic infections. Therefore, the risk of not sanitizing loppers may be less than the risk of going slower. For example, a 2008 research paper by researchers from Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada found that pruning as soon as disease was detected greatly reduced fire blight damage compared to pruning out symptoms starting in August. In Bartlett pear, WSU researchers reported in a 1990 trial that a two-week delay in removal resulted in a sixfold increase in the amount of plant material that had to be removed.

First- to third-leaf trees

In very young trees, fire blight infections move quickly through the tree. When infected, removal and destruction of the whole tree is recommended. After removal, a concentrated application of Actigard (acibenzolar-S-methyl) to adjoining trees can increase the plant’s defense system and reduce the likelihood that adjoining trees are also infected.

Actigard

Applying a concentrated solution of Actigard as part of pruning therapies can reduce the severity of re-occurring fire blight cankers. Oregon State University studies over five years found that applying Actigard when removing fire blight infection can reduce both the proportion of trees in which fire blight reoccurred and the rate of canker expansion. Apply concentrated Actigard with an up-and-down motion to a 2-foot section of the central leader or major scaffold near where the fire blight infection was removed. Use the labeled rate of 1 ounce per 1 quart of water with 1 percent silicone-based penetrant.

Conclusions

—Timely removal of fire blight cankers can reduce rootstock blight and tree death.

—Pruning 12 to 18 inches below the visibly diseased (cankered) tissue into 2-year-old wood generally reduces canker re-formation caused by systemic movement of fire blight bacteria through the plant.

—Aggressive removal 2.5 feet below cankers was generally not better than removal at 12 to 18 inches.

—Breaking can leave many active infections in the orchard.

—Leaving a stub can reduce canker re-formation on structural wood.

LEARN MORE ONLINE: To learn more about the latest research and recommendations on fire blight management, head to Washington State University’s website: bit.ly/wsu-fire-blight-management.

—by Tianna DuPont, Aina Baro, Ken Johnson, Kerik Cox and Kari Peter

Tianna DuPont is an extension specialist at Washington State University; Aina Baro is a postdoctoral researcher at WSU; Ken Johnson is a pathologist at Oregon State University; Kerik Cox is a pathologist at Cornell University; and Kari Peter is a pathologist at Penn State University. This work was supported by the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission and the United States Department of Agriculture Specialty Crop Research Initiative.

Leave A Comment