Grapevine trunk diseases lurk pretty much everywhere grapes are grown, but best management practices are not well understood in younger wine regions.

For Minnesota wine grape growers, the prevalence of these wood-decay pathogens came as a surprise in 2018; when visiting viticulturist Richard Smart raised the issue of wood cankers, it put a previously unknown problem on the top of the industry’s priority list.

Two years later, thanks to a rapid response grant from the University of Minnesota, researchers are beginning to understand which pathogens are most common in Minnesota vineyards, said Davy DeKrey, a graduate student working with forest pathologist Robert Blanchette to study grapevine trunk disease.

Actually, diseases, DeKrey said. Grapevine trunk disease is a complex that encompasses dozens of different fungal pathogens that have been identified in grapevines so far. “The naming is very confusing,” he said.

The complex includes pathogens commonly known as esca, eutypa, phomopsis dead arm, and botryosphaeria canker, said Annie Klodd, fruit extension specialist at the University of Minnesota. At this point, it’s more important that growers understand they have a wood-decaying pathogen than which one they have, she said, but more research will illustrate if some of the pathogens pose a more serious threat than others in Minnesota climate conditions.

Survey

Generally speaking, grapevine trunk diseases (GTD) are rarely found in young vineyards. But as vines, and wine regions, mature, the slow-moving decays can become more prevalent and reduce vine vigor and yield.

“Our industry is a lot younger than California,” where management of trunk diseases has been more extensively studied, DeKrey said. When his survey started, “the bulk of the vineyards were starting to come to about 10 years old; that’s when you’ll start to see the vines decline from GTD.”

Symptoms may have been overlooked in the past because trunk diseases may be confused with winter injury when dieback in the cordon occurs, Klodd said. But the polar vortex of 2019 was actually to blame for significant vine loss last year, which some panicked growers mistakenly attributed to the newly discovered trunk diseases.

“I was visiting vineyards with sections that were all dead to the ground. That’s not something trunk disease can do,” Klodd said. “It’s much more of a gradual loss.”

For his first survey in 2019, DeKrey took samples from 34 vineyards in Minnesota and Wisconsin, looking at samples from trunks, cordons, roots and shoots of 18 different cold-hardy cultivars. The next research question, for which he is currently collecting data: Are the pathogens hitching a ride on plant material from nurseries?

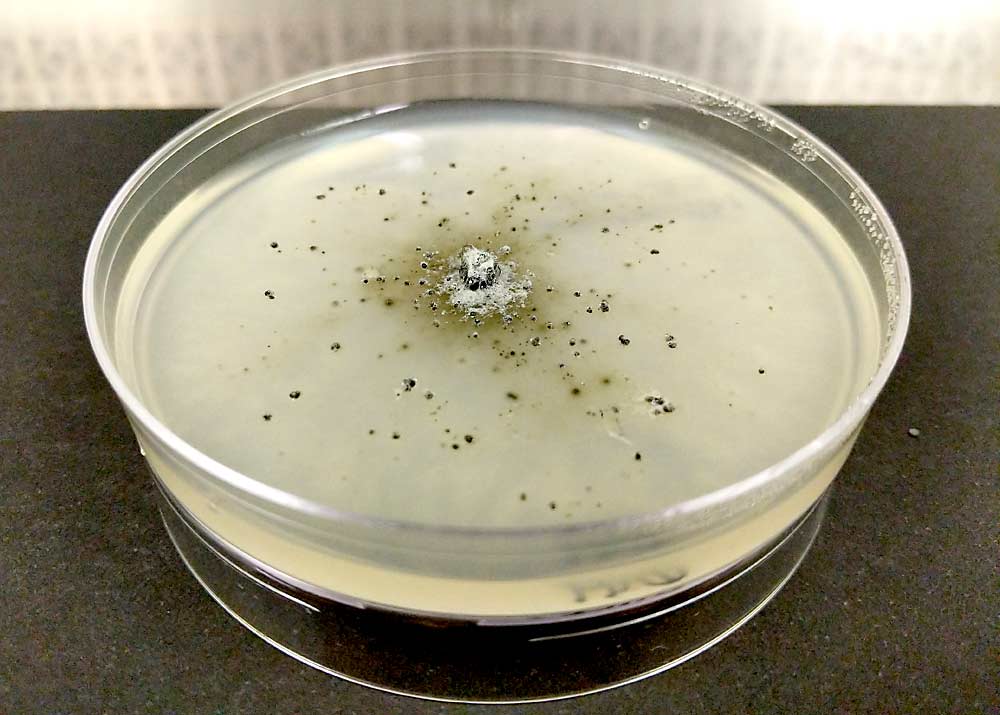

“The baseline of the project is to establish who are these fungi,” he said. He is still crunching some data, but the most prevalent pathogens seem to be Cytospora viticola and Diaporthe ampelina, relatively fast-growing canker-causing fungi, he said. Sometimes rot fungi follow these canker infections, layering the decay.

Growers were most concerned about bot canker, which Smart referenced during his visit, referring to fungi in the Botryosphaeria family, but Botryosphaeria species themselves have been relatively rare, DeKrey said. At this point, researchers don’t know enough to say which pathogens may be more of a concern, so he and Klodd both cautioned that the presence of any trunk disease pathogen should prompt growers to think about pruning precautions and vineyard sanitation.

Management

Once growers find wood rot in their cordons, which looks like a wedge of discoloration, they should cut back until the wood is clear, to remove it all. Wetting the wood can make it easier to see the discoloration, DeKrey said.

Pruning wounds give these pathogens an entry point, so growers should prune at less risky times and sanitize pruning tools as best management strategies, DeKrey said. Research out of British Columbia suggests that for grape growing regions with cold winters, the winter months are the best time to prune to protect the pruning wounds from fungal infection.

But there’s winter, and then there’s Minnesota winter. Convincing someone to prune in January, when it’s 5 degrees Fahrenheit and there’s 3 feet of snow in the vineyard, is tough, Klodd said.

A few growers did shift to winter pruning last season, but it’s far from the norm, she said. Klodd and DeKrey will be working with one grower who has kept detailed records, to see if they can correlate pruning dates with trunk disease infection and, they hope, provide Minnesota-specific data that might help make the case that winter pruning is worth the hassle for disease prevention.

“If there’s a demonstrated benefit, I think that will help us provide more information to growers,” Klodd said.

Klodd also recommends, based on research from other regions, that growers try latex paint to protect wounds, especially if they are renewing a trunk. But again, it’s a practice she wants to test to make sure the paint is sufficiently protective in really cold, damp conditions.

“It’s not going to hurt, so they might as well try it,” she said. •

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment