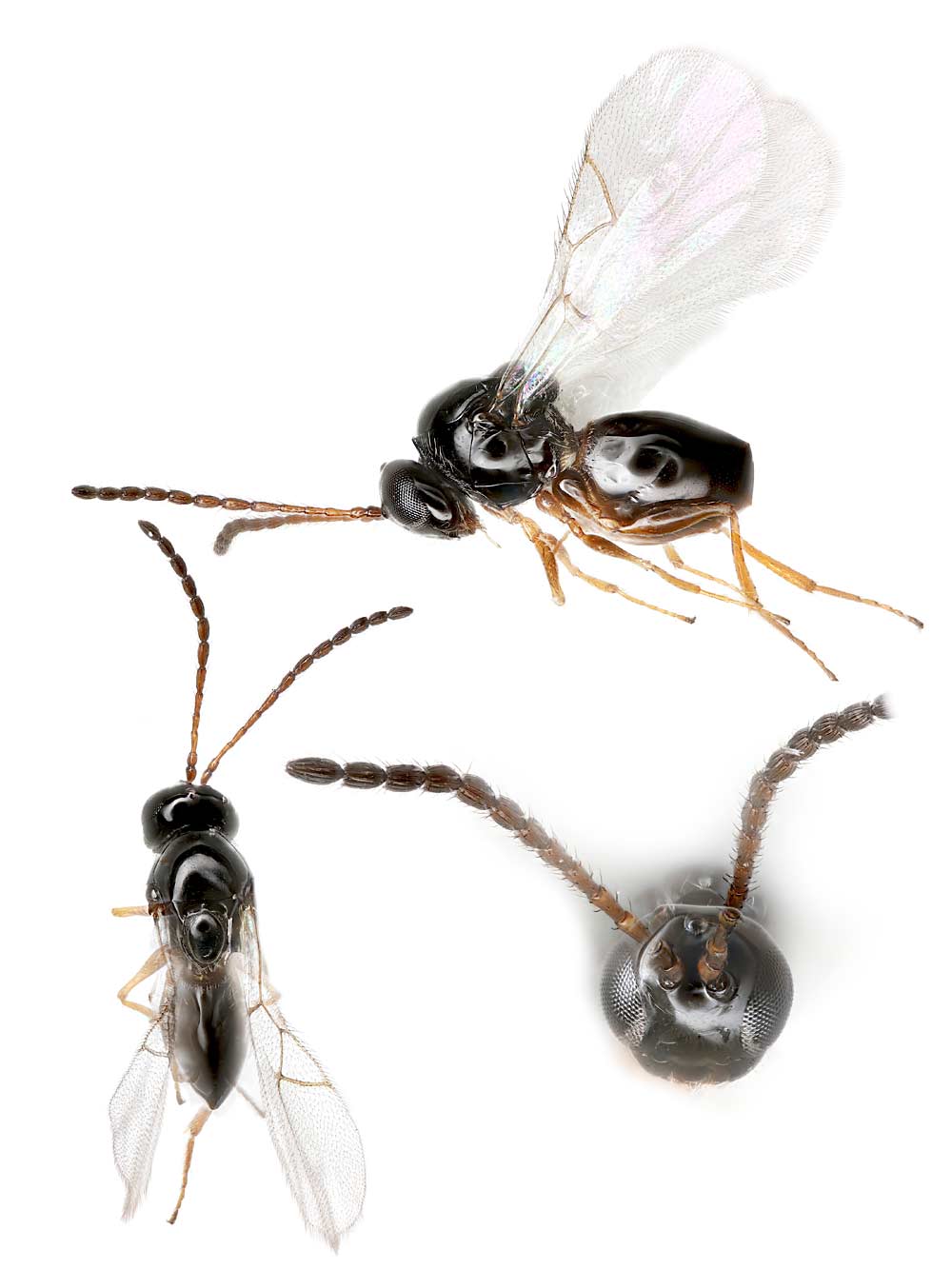

The integrated pest management toolbox for spotted wing drosophila may be getting a major boost. After years of study, federal regulators authorized the release of Ganaspis brasiliensis, a tiny wasp discovered in SWD’s home range and with a strong preference for the pest.

“We’re all extremely excited about it,” said Vaughn Walton, an Oregon State University entomologist who has spent a decade researching SWD control. “We’ve been waiting such a long time for this.”

The wasps are now being sent from quarantine facilities to multiple federal and university labs that will rear large quantities of Ganaspis for release, said Jana Lee, an entomologist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Research Service in Corvallis, Oregon. Ramping up such efforts is complicated, and it’s unclear how many wasps will be available for release trials this year, she said in January.

But Ganaspis, it turns out, is already in the Pacific Northwest.

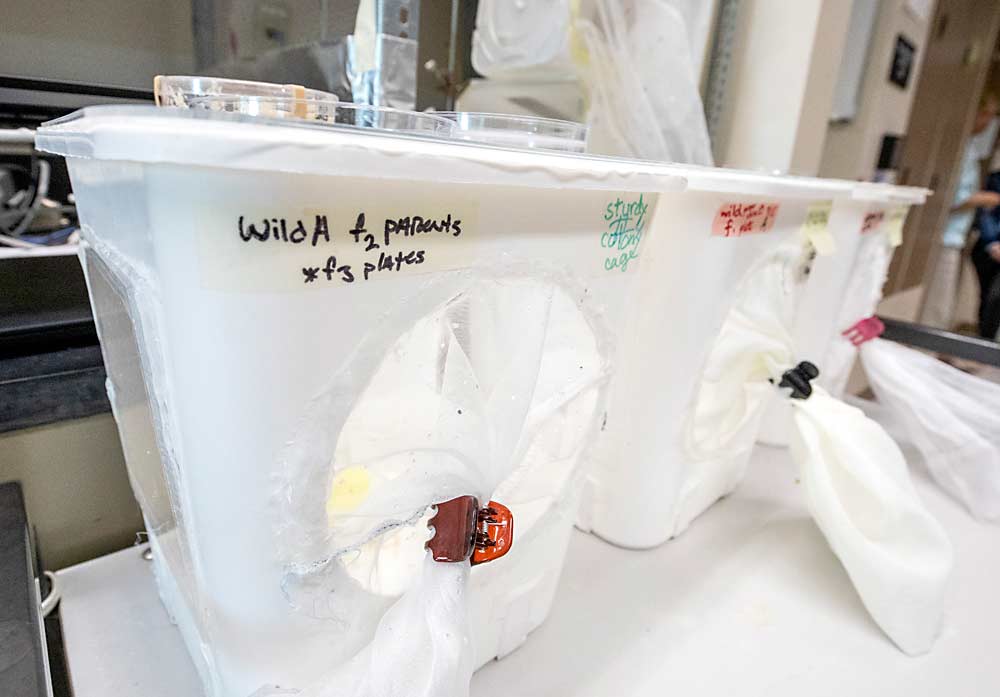

Last fall, Washington State University entomologist Betsy Beers found the parasitoid in a patch of wild blackberries in Western Washington near the Canadian border. Scientists in British Columbia first detected it in 2019. She was able to collect some infected fruit with parasitized larvae in them to start a small colony in her Wenatchee laboratory.

“I want them alive and well,” she said.

Beers also collected another SWD-targeting parasitoid wasp, known as Leptopilina japonica, last summer, thanks to a tip from another entomologist who found one in an Asian giant hornet trap in northwest Washington’s Whatcom County in 2020. Leptopilina was another candidate from Asia which the USDA regulators reviewed, but it was not approved for release because it has a slightly wider host range than Ganaspis, Beers said.

“It’s great to have an inventive population that just showed up,” she said. Building up colonies to supply releases can take time, and things can go wrong. “But we have a giant backup for our colony — it’s called Whatcom County,” she said.

Areawide efforts

Up and down the West Coast, scientists will study Ganaspis releases as part of a USDA-funded Spotted Wing Drosophila Areawide Project led by Lee. The field-scale project will build on lab studies of the parasitoid led by University of California, Berkeley entomologist Kent Daane, Lee said.

The project will look at four pairs of commercial fruit production sites — cherries in Washington, cherries and blueberries in Oregon, and caneberries in California — to see how growers’ standard management techniques compare to new approaches, including biocontrol releases and other alternative management strategies that growers feel comfortable using, she said. (See “IPM ambitions.”)

Growers should remember that the wasps need hosts, she said, so they shouldn’t expect to have strong biocontrol populations in blueberry fields or cherry orchards where they have aggressive control programs minimizing SWD damage to fruit.

The areawide approach uses large sites, encompassing hundreds of acres. Last year, the project started with just collecting baseline data, looking for areas with lots of SWD, Lee said. This year, researchers will release the biocontrols in native vegetation surrounding farmland, as the wasps are very susceptible to insecticides. The hope is that they will reduce the overall pest pressure by reducing SWD populations in the landscape.

Monitoring for Ganaspis this year across that large area should help scientists learn how to release them in the future, she said.

“We monitor for them by collecting fruit with SWD and hold it and see if the parasitoids emerge,” she said. “That works well in wild Himalayan blackberry, those border hosts that aren’t sprayed.”

Growers’ fruit, on the other hand, is usually devoid of SWD larvae, which is the goal.

“So, it wouldn’t be fruitful to monitor their fruit,” she said. Instead, researchers use “sentinel traps.” They place infected blueberries from their lab colonies inside a container, protected by mesh that the parasitoid wasps can get through but which blocks other fruit flies from contaminating the samples.

In Oregon’s Willamette Valley, as in much of the Eastern U.S., the natural landscape surrounding crop production has plenty of hosts for SWD. In arid Central Washington, the surrounding sagebrush may pose more of a challenge for the parasitoids to establish.

Still, Beers is optimistic. “It’s likely the parasitoid can establish everywhere the pest is, but we don’t know yet,” she said. “That’s the great adventure we are embarking on right now, as we are on the threshold of releasing them.”

Bonus biocontrols

Discovering populations of both Ganaspis and Leptopilina in Western Washington gives Beers and her colleagues a chance to rear and release them throughout the state, but only the USDA-approved strain of Ganaspis can be released in other states.

“It’s a very, very conservative permitted process,” Beers said. “It has to have a very restricted host range, otherwise they are not going to give you a permit to release it.”

But Leptopilina, with a wider host range, might be better able to survive in a variety of habitats, Beers said. It also seems easier to rear, so far.

With two parasitoids, there is the promise of complementary biocontrol, she said.

She also shared samples from her small colonies with the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service laboratory in Wapato, in the Yakima Valley, which has more capacity for rearing. This year, her main priority is to learn how to rear them before beginning releases.

Several years ago, Oregon researchers found another parasitoid wasp that attacks the pupae of SWD and other fruit flies, known as Pachycrepoideus vindemmiae. Lab trials at OSU determined that it was very effective at parasitizing SWD, but in the field, it’s a generalist, Walton said.

“We have done some augmentation studies where we release Pachycrepoideus; there’s not restrictions on releasing them since they are present,” Lee said. “The question is how much they contribute.”

The more biocontrol options on the landscape, the better, Beers and Lee agreed, although there is still much to learn about how they might function in U.S. landscapes.

“It’s an attempt to relevel the playing field and restore the balance of nature as the pest is suppressed to the same level as in its country of origin,” Beers said.

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment