With help from elevated slopes and a climate tempered by the Atlantic Ocean, Nova Scotia, Canada, has grown apples for 400 years, ever since Europeans first settled there.

It took Honeycrisp, however, to bring the Nova Scotia industry into the 21st century.

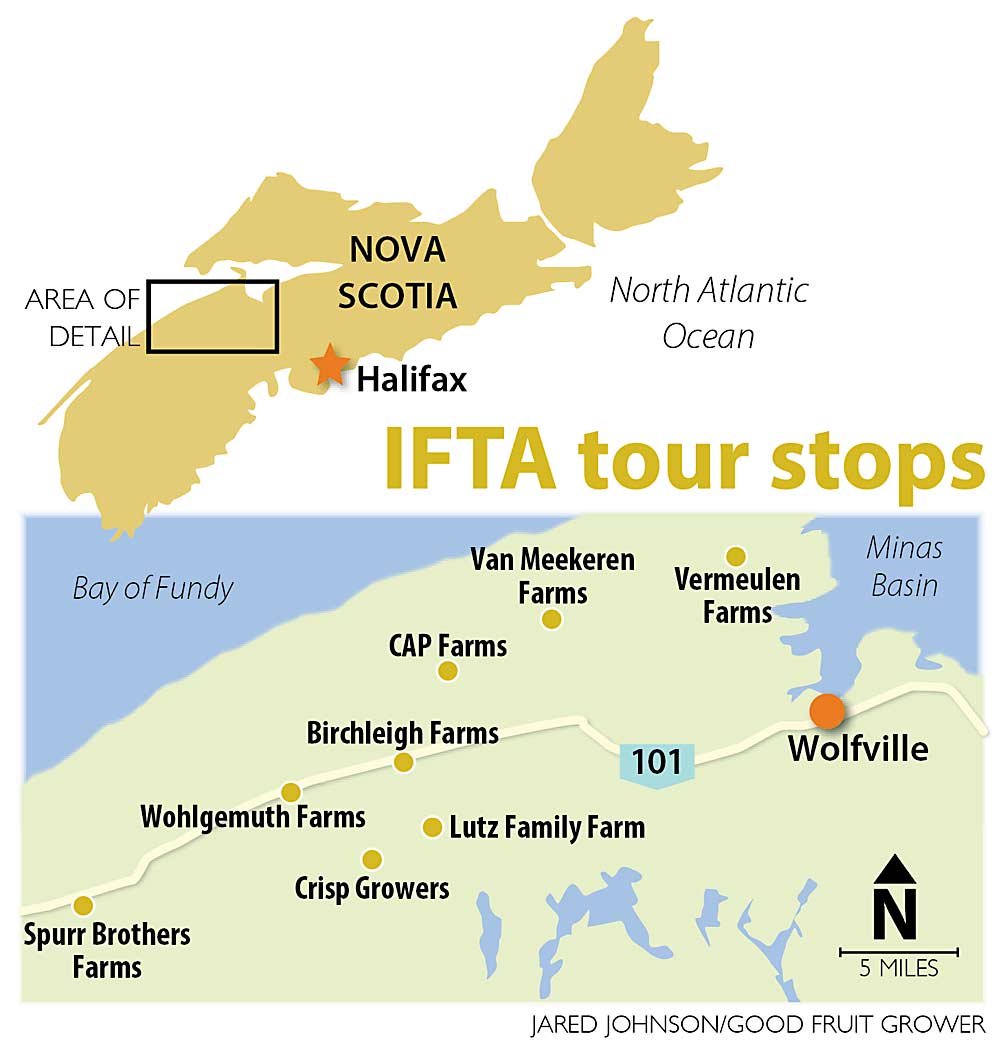

The International Fruit Tree Association witnessed the evolution firsthand in late July when it spent two days touring orchards on the slopes of the Annapolis Valley, where most of the province’s 5,000 acres of apples grow. The IFTA tour saw modern varieties growing in high-density blocks, cutting-edge technology and a fruit industry that, like others, is adjusting to an increasingly unpredictable climate.

Case in point: Massive rains and historic flooding washed out many of the province’s roads in the days leading up to the tour, making it difficult for some IFTA members to get to the Annapolis Valley. Fortunately, the orchard blocks were above the flooding and the roads were dry by the time the tour started.

Nova Scotia orchards receive about 50 inches of rain annually, and daily summer temperatures average 68 degrees Fahrenheit. The province’s commercial apple industry thrived from the late 1800s to the mid-1900s, shipping most of its apples to European markets. But those markets dried up during and after World War II, and many growers were left with older varieties like Ben Davis and Baldwin, often destined for processing markets.

The introduction of Honeycrisp in 1996 “completely changed the dynamics” of the Nova Scotia industry, said grower and IFTA tour guide Larry Lutz. The variety fit the provincial climate like a glove, coloring well during the cool evenings, and its high returns encouraged growers to reinvest in their orchards, also giving younger generations a reason to return to the family farm, he said.

The tour

The IFTA tour stopped at eight farms in the Annapolis Valley. Most were similar in size, with a little more or little less than 100 acres of apples. Honeycrisp is now the most profitable and widely planted variety, but growers also have a lot of Ambrosia, Gala and club varieties such as Minneiska (marketed as SweeTango) and Pazazz. Most new plantings are spaced 3 feet by 12 feet on Malling or Geneva rootstocks.

IFTA tour stops included Birchleigh Farms, where attendees learned about the farm’s replant trials and innovative management practices for tackling climate change. The tour discussed apple storage and postharvest challenges at vertically integrated Van Meekeren Farms.

At Vermeulen Farms, a 450-acre fresh fruit and vegetable farm run by Andy and Ben Vermeulen, IFTA members saw raised-bed strawberries covered by plastic tunnels and learned about Canada’s farm labor challenges and Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program, which is similar to the U.S. H-2A program. Lutz also discussed labor at Lutz Family Farm. Specialty crop growers like him rely on the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program to stay in business, he said.

Another stop was Crisp Growers, a 250-acre orchard owned by 14 apple-growing families and Scotian Gold, the cooperative that packs 60 percent of the province’s apples. When they collectively acquired Crisp Growers in 2013, the new owners aggressively modernized and replaced older trees with high-density plantings.

Other tour stops included Spurr Bros. Farms (see “Growers grin and pear it in eastern Canada”), CAP Farms — where the visitors saw a high-density block of Ambrosia and a homemade over-the-row sprayer — and Wohlgemuth Farms, where speakers discussed results from an NC-140 Gala rootstock trial and a pneumatic defoliation trial. New technologies — including an autonomous tractor and sprayer and a digital crop load management tool — were displayed at some of the stops.

Read future issues of Good Fruit Grower for more reporting from IFTA’s Nova Scotia tour, including a deep dive into Ambrosia horticulture and more technology highlights in our October issue.

—by Matt Milkovich

Leave A Comment