Phil Tregunno’s Tregunno Fruit Farms Inc. near Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario, Canada, has 700 acres of stone fruits and grapes. The grapes now account for a quarter of the farm’s production. Peter Mitham for Good Fruit Grower)

Ontario’s stone fruit industry is renewing its focus on local markets following a lengthy battle with plum pox virus (PPV) and the closure of key processing plants.

Niagara remains the only region in Canada harboring the virus, also known as sharka.

The disease was declared eradicated in neighboring Pennsylvania following an intensive battle—though it remains a presence in New York—but with no known occurrences in commercial orchards since 2010, 15 years of monitoring will come to an end in 2016.

Regulatory controls will replace disease management to “mitigate the spread of PPV outside of the regulated area,” says the Canadian Food Inspection Agency.

Meanwhile, growers have been rebuilding their orchards. Control measures have cost industry and private homeowners 377,402 trees since 2000 (equivalent to a fifth of the province’s commercial stone fruit plantings in 1999), compounding the impact of the Cangro plant closure at the end of June 2008. The plant, which was the region’s last fruit processor, closed after 112 years of operation.

The losses in trees and processing capacity have spurred growers to seek alternatives; some have turned to wine grapes, while others have reinvested in fresh-market varieties that cater to consumers with an increased appetite for local produce.

“There’s been quite a demand in the past for some extra wine grape acreage, and that’s where we’ve seen the shift,” said Phil Tregunno, chair of the Ontario Tender Fruit Growers and owner of Tregunno Fruit Farms Inc. near Niagara-on-the-Lake, which has 700 acres of stone fruits and grapes. “A lot of it was replanted with better (stone fruit) varieties, too.”

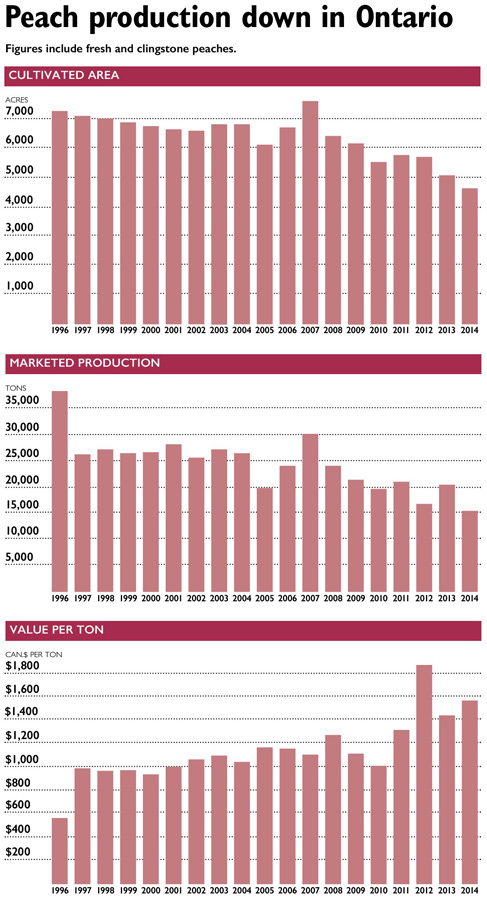

A look at the numbers is telling.

Between 1999 (the year before the discovery of plum pox virus) and 2012, the number of processing peach trees in Ontario fell by 70 percent. The overall stone fruit tree count fell by 7 percent..

However, fresh market peach plantings have increased 18 percent over the same period, and plantings of sour cherries and plums have also increased. Since 2009, plantings of apricots, nectarines, and prune plums have all increased.

The plantings, however, are on smaller acreages.

Figures from Statistics Canada indicate the area planted to stone fruits has dropped from 10,122 acres in 2007 to 7,533 acres in 2014 (data are not available prior to 2007; data since have depended on an industry-wide GPS mapping initiative).

The shift in acreage points to a much-needed renewal of the Ontario stone fruit industry driven as much by disease as the loss of local processing capacity.

While production is down about 25 percent from a decade ago, it has stabilized at about 30,000 tons a year. However, orchards are more productive, making more efficient use of the land base. A single acre now yields fruit that sells for twice as much as it did a decade ago.

Source: Statistics Canada. (Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower illustration)

Tregunno said the shift, whether to wine grapes or new varieties of stone fruit, has helped stabilize production and created exciting opportunities for the years ahead.

“There are quite a few growers who have diversified their operations by growing some wine grapes, then there are some who have completely switched over,” he said, noting that while his farm primarily has tree fruits, grapes account for a quarter of its production. “We grow wine grapes also, but we’ve actually purchased some farms and shifted them into tender fruit, too.”

Yet without complete eradication, ongoing vigilance is required to ensure plum pox virus doesn’t lead to another massive pull-out of trees.

“We were disappointed they didn’t follow through. They got 90 percent through on the program, then they stopped,” Tregunno said.

Canada spent $193 million on eradication and control efforts through March 2011, the point by which it initially expected to eradicate the disease.

However, the concentration of orchards in the Niagara region made it impossible—without imposing a cure worse than the disease—to establish the wide buffers that helped Pennsylvania declare the virus’s eradication.

“We would eradicate the disease but at the detriment to the industry, which we don’t want,” federal plant protection specialist Eric Wieringa told Good Fruit Grower in 2010.

Instead, controlling the disease became the focus. The industry developed a Prunus certification program to test propagative material for PPV and other viruses, and new peach varieties such as Veeblush and Virtue (both developed by the University of Guelph) were sought for replanting orchards.

Since 2011, an additional Can.$17 million has been budgeted to develop regulations and best management practices to control the disease.

Beginning in 2016, these regulations will complement monitoring and management to prevent the spread of the virus.

Activities will include sampling PPV-susceptible trees both inside and outside the perimeter of the Niagara region to determine if the disease is spreading; monitoring the Niagara quarantine area to ensure that no susceptible trees or plants are being propagated; and monitoring the quarantine area to ensure that susceptible trees or plants are not moved from the area (PPV is associated primarily with the sharing of infected plant material, so the movement of fresh fruit isn’t restricted).

While no commercial growers have reported the disease, Tregunno suspects some of the fresh market varieties that growers have embraced may not exhibit symptoms.

However, the disease remains a risk, given the number of trees in residential areas (where the only infected tree has been found since 2011) as well as its presence in neighboring New York state, where a nine-year control effort remains ongoing.

Michael Kauzlaric, a researcher with the Vineland Research and Innovation Centre engaged in outreach to stone fruit growers, agrees that the disease remains a risk, but he’s also confident that the new protocols will protect growers.

“I have not noticed any of the newly planted varieties to be less susceptible to PPV,” he said. But “the CFIA and Ontario tender fruit industry have taken great steps to ensure propagating budwood has been virus tested in an attempt to plant virus-free acres.”

All dollar amounts are in Canadian dollars; a Canadian dollar is worth approximately 77 U.S. cents as of November 2015. •

Leave A Comment