In early March, Steve DaValle’s crews used a repurposed trailer as a poor-man’s platform to string wire for V-trellises throughout his Lodi, California, apple orchard.

The manager for Grupe Operating Co. has been switching from vertical to V-trellises and grafting to new Gala strains to not only survive but improve in an industry that has been shrinking in California for decades.

“We’re battling,” DaValle said. “Let’s put it that way.”

California apples are not what they were and will never be again. The once hotbed of apple production, home of John Steinbeck’s orchard tales, hardly makes a speck on the U.S. production charts anymore.

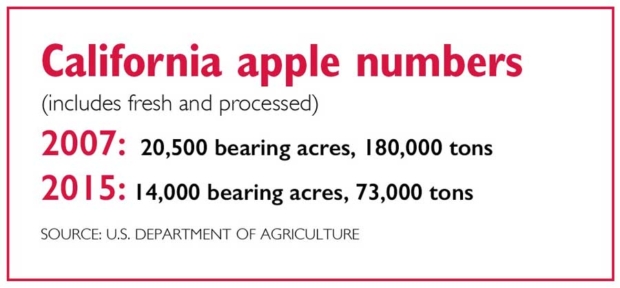

Growers harvest roughly 17 percent of the fresh apples they did 20 years ago, while acreage has dropped by a third in the Golden State in the past 10 years or so.

However, California growers are not only hanging in there, they’re growing and innovating in places, hoping to capitalize on the seasonal excitement of fresh apples.

“We’re the first fresh apples to be harvested in America,” said Jeff Colombini, another Lodi area grower. “We’re a niche market.”

Washington’s massive acreage, controlled-atmosphere rooms and cold storage allow Northwest packers to stretch the apple season throughout the year, selling out one crop just as the new one comes off the trees.

California does little of that, instead marketing apples much like cherries, as a get-it-while-it’s-fresh crop.

“That’s what gets consumers excited,” said Kevin Ott, president of the California Apple Commission. “We pick ’em, we pack ’em, we ship ’em.”

History of decline

Apples came to the Golden State following the mid-1800s Gold Rush, when transplants from the East Coast and other nations stayed to plant fruit trees in areas such as Watsonville, which is near the Bay Area, and Placerville in the Sierra foothills.

Codling moth in the 1930s took a toll, but even in the 1980s, Granny Smiths grew up and down the Central Valley on thousands of acres, mostly in the southern, warmer areas, Colombini said.

The story goes that in about 1985, a chance visit by a Taiwanese buyer to a California apple packer led him to Fujis, previously used primarily as a pollinizer for Grannies.

The variety became a hit for the export market within a few years and expanded through the 1990s.

California grew a sweet Fuji but struggled to get color. In fact, Taiwanese buyers nicknamed the Fuji the Green Dragon, Colombini said.

In 1998 or so, supply caught up with demand and overseas customers grew more particular about color. Orchardists began removing orchards over the next four or five years.

Meanwhile, crops like walnuts, almonds and pistachios began replacing apples due to their low labor costs with mechanical harvest. Employers in California are ramping up for a $15 minimum wage by 2020.

“It’s difficult to make money growing any crop that can be grown equally successfully in any other state … the caveat is unless you’re harvesting it when no one else is harvesting it and selling it when no one else is selling it,” Colombini said. “And that’s really the bottom line.”

Colombini estimates his apples cost between $4,000 to $5,000 per acre in labor. He hires about 200 seasonal workers to pick his 500-plus acres of apples. He could harvest the same acreage of walnuts with six people. He diversifies in walnuts and oil olives.

Innovation, investment and the future

Growers are experimenting and spending money on new plantings, grafts and technology when they can.

Colombini has a test plot of Honeycrisp, not widely grown in California, that he will put under shade cloth when mature.

He otherwise grows mostly Gala and Fuji, but also has Granny and Pink Lady, an apple that he believes performs well in California.

Galas are probably California’s most common variety now, as growers hope to capitalize on the early season, which runs about four weeks ahead of Washington.

“We’ve had a little marketing window in the Gala business” DaValle said.

Over the past 10 years, he and his assistant Kevin Baroni have been grafting Fujis and Cripps Pink over to high-color trademarked strains of Gala such as Buckeye, Gale and Ultima.

They have one more block of Imperial, an older Gala strain, but plan to convert it this coming winter. Of their 100 acres of apples, only half are currently in production due to all their changes.

They still have 16 acres of Fujis and will leave those for a few years at least, Baroni said.

They also are converting from vertical trellises to V-trellises to help fill the space and boost yields from 40 to 75 bins per acre in their 14-foot rows, something they consider crucial to survival.

“You go to the super high-density V-trellis or you’re done,” Baroni said.

They call their trellis projects minor, reusing the same anchors, posts and overhead cooling sprinklers and spending about one-third of what it would typically cost to start from scratch.

They have eight full-time employees and do as much of their own in-house construction and training, bending the limbs to the brink of breaking to keep them horizontal.

“We’re cheap,” DaValle said with a laugh.

They hire up to 100 extra workers during the apple season for picking. Besides apples, they grow walnuts, cherries and oil olives.

With growers such as Colombini and DaValle, nobody suspects the apple industry will disappear. The California Apple Commission estimates it will plod along between 1.5 million and 3 million boxes.

“I don’t think it’s going to get smaller, but I don’t think it’s going to get much bigger,” Colombini said.

Leave A Comment