Nearly 10 hours into the first day of a new research trial on wine grapes, Washington State University Assistant Professor Tom Collins writes harvest notes on a Riesling grape sample collected from a smoke-filled row at the WSU Prosser, Washington, research vineyard in July. Collins, with the assistance of research technicians Chris Sorenson, left, and John Ferguson, center, is studying how wildfire smoke may impact wine grape flavors. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

The catastrophic wildfires of recent years raise obvious, immediate concerns for growers to protect people, equipment and orchards and vineyards from damage.

In premier grape-growing regions, wildfires can have a longer lasting effect: the possibility of a wine vintage being tainted by smoke.

Researchers have already established that grape cultivars can take in contaminants from wildfire smoke, resulting in undesirable sensory expressions in the wine — smoky, ashy, burnt.

It’s known as “smoke taint.”

However, researchers don’t yet know exactly how much smoke must be present in the vineyard, or for how long, to experience perceptible taint in the resulting wines.

More also needs to be known about how to alleviate severe taint in wine to salvage it.

It’s a tricky study question, because wine is also a function of how the winemaker produces it, says Tom Collins, assistant professor in Washington State University’s Wine Science Center in Richland, Washington.

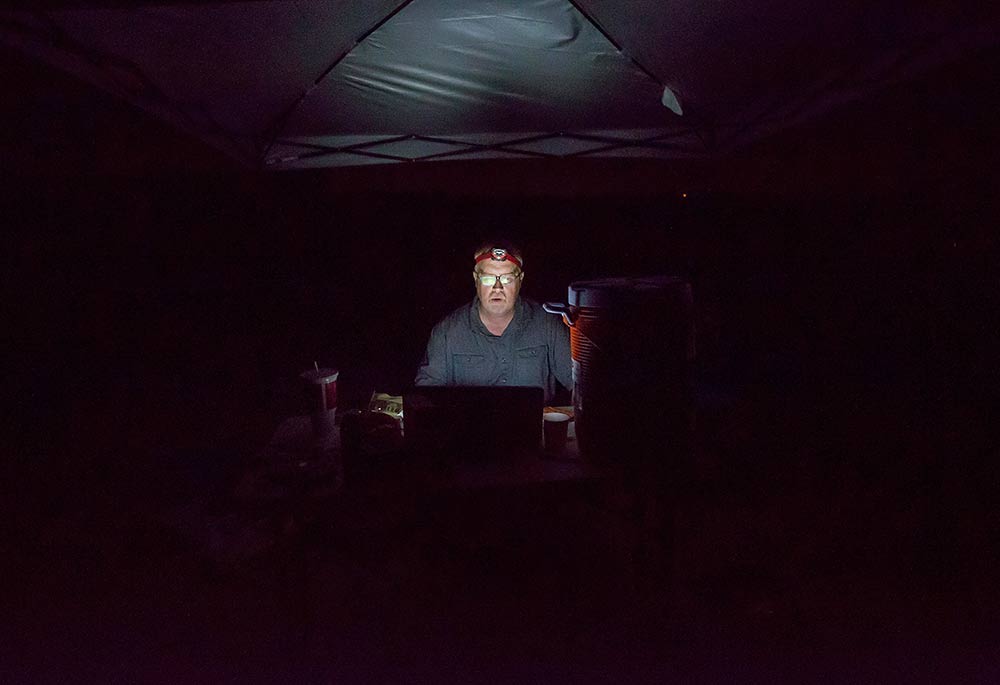

Collins closely monitors frequently changing smoke levels within his trial enclosure about 10:30 p.m. July 28, 2016. Sensors set up throughout the enclosure, in the smoker and outside of the enclosure provided a minute-by-minute appraisal of air quality conditions. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

Collins is researching the issue of smoke taint — both in the vineyard and in the winery — with funding from the Washington Wine Commission.

“I don’t think we’re going to see the issue of wildfires going away any time soon,” he said. “And as we continue to plant more vineyards in the state and elsewhere, the likelihood that we’re going to have this intersection of vineyard and wildfire smoke is only going to get greater.”

Smoke in the air

In his research project, Collins is using a customized smoker and exhaust hoses with attached fans to evenly distribute smoke and a one-of-a-kind vine enclosure to help mimic smoke levels common in wildfires. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

In 2008, a severe lack of rainfall and windy conditions made for a tough summer wildfire season in California.

At that time, Collins had just assumed a position in research and development for Treasury Wine Estates, a role that ended up requiring him to assess the resulting wines from that vintage for taint.

Cabernet Sauvignon was most affected and, to a lesser extent, Merlot and Cabernet Franc, he said.

It was clear there was an impact to the grapes. In the years since, researchers in Australia and the U.S. have been examining the issue of smoke taint, leading to development of some tests for smoke taint in wine.

the researchers smoked post-veraison Riesling grapes the first night of the trial. They carefully selected clusters at different time intervals through the 18-hour marathon, wrapped them in aluminum foil, then bagged them in coolers before taking them to the university winery the next day. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

What is less clear is the relationship between the smoke intensity and time, or as Collins puts it, “at what point do you say this fruit is not going to be salvageable.”

Better understanding that relationship will help growers who find themselves in that situation, because taint is invisible on the leaves or fruit and only appears when the wine is produced.

The other goal of the project is to better understand all the markers, the compounds, that should be measured to establish the severity of the smoke taint in a wine.

Smoke taint is created by smoke compounds that bind with sugar molecules to form glycosides.

These glycosides break down in the acidic wine, releasing the smoke compounds and creating a smoky aroma or taste.

“It’s clear from all the previous research, both what we did in California and what has come out of Australia, is that it’s not sufficient to just measure the free smoke compounds,” Collins said. “We also need to know something about the pool of sugar-bound compounds as well.”

Collins’ wildfire smoke system consisted of a customized smoker, exhaust hoses with attached fans to evenly distribute smoke, and a one of a kind vine enclosure to help mimic smoke levels common in wildfires. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

For this study, Collins and his team constructed hoop houses to cover some 60 vines each of Cabernet Sauvignon and Riesling grapes in research orchards at WSU’s Irrigated Agriculture Research and Extension Center in Prosser, Washington.

Using a smoker, he pumped fumes into the house, monitoring the results with particle counters. His team will analyze leaves, fruit and wine to determine the impacts of the smoke.

“We covered a significant piece of real estate with these hoop houses so that we have enough grapes to make enough wine for us to do follow-up work to understand how these compounds are extracted from the fruit, and to start to do trials looking at how we might be able to remove these compounds or diminish the effects in the resulting wines,” he said.

The goal of the first year of the three-year study was to establish methodologies for the research.

Collins is still conducting a preliminary analysis of the fruit, leaves and resulting wine and hasn’t gotten through enough samples to draw any conclusions yet. He expects to have some initial results to present at the Washington Association of Wine Grape Growers annual meeting in February.

In a long-exposure photo at right, Collins is seen in three areas because when smoke levels dipped, Collins would move from his monitoring station, right, to the smoker, left, to add cut lumber to the smoker, then back again to watch the smoke levels increase inside the enclosure. The research team would continue this work for nearly 18 hours. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

Where’s there’s smoke…

As part of a study on the effects of wildfire smoke on wine grapes Collins also needs to examine grapes from control blocks of Riesling and Cabernet Sauvignon that have not been exposed to smoke. But, as always, Mother Nature is the one in control.

Collins had just finished smoking the Riesling block on a Friday afternoon. The next day, two wildfires started to the south and east of the vineyard, and Collins awoke Sunday to the smell of smoke at his home some 30 miles east.

“We still had the smoke monitoring system in our trial, so I had those set up in our vineyard so I could monitor whether we were getting any wild wildfire smoke, if you will, as opposed to the domestic stuff,”

Collins said with a chuckle. Fortunately, the vineyard didn’t get much “wild” smoke. “As it turned out, it didn’t compromise our trial, but it certainly got everyone’s attention,” he said.

However, Collins collected wines from nearby vineyards that were affected by the wildfires.

He intends to analyze those wines, along with the wines from the control vineyards and the intentionally smoke-tainted wines from the study, to compare the results.

– by Shannon Dininny / photos by TJ Mullinax

Hello and thank you for this information. Have you done or do you know of any studies on the effect of exhaust fumes on vineyards located next to highways and interstates?