A few extra hands at harvest is not cutting it anymore.

America’s farmers this year will likely hire H-2A guest workers in greater numbers, for longer periods and for a wider array of chores than ever before.

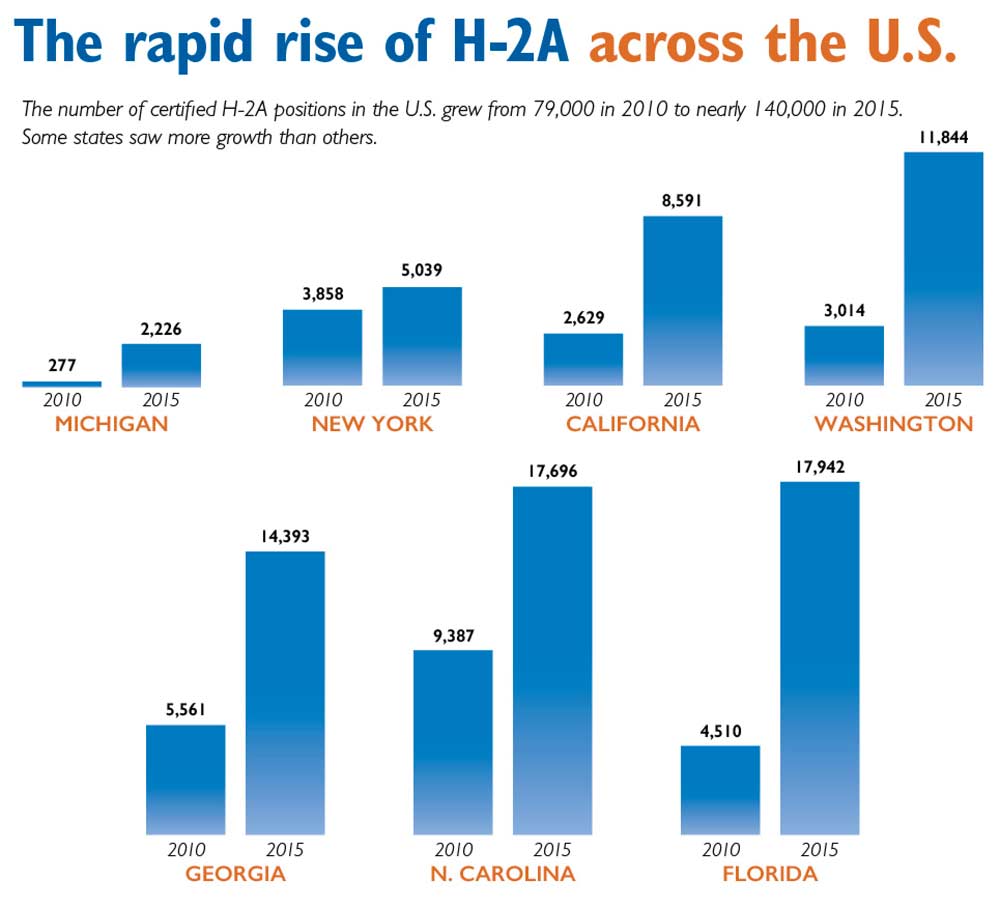

Nationwide, the number of H-2A workers is expected to top 200,000 this year for the first time, following years of steady growth in the program.

The surge continues despite the complexities, cost, risk and political question marks hovering over immigration issues.

On one hand, President Donald Trump’s administration has promised more aggressive enforcement of illegal immigration, but he has publicly supported the H-2A program. His family uses it to bring in workers at its vineyards and winery in Virginia.

The program may hit its limit someday, said Mike Gempler, executive director of the Washington Growers League, a labor services nonprofit in Yakima, Washington.

Even with the increased use of the program, H-2A workers still make up less than 15 percent of the state’s agricultural workforce and less than 10 percent of the nation’s.

Dan Fazio, CEO of Wafla, a Lacey, Washington, seasonal farm employment nonprofit, advocates reforms to the H-2A program that would bring down the costs and streamline the paperwork through numerous state and federal agencies.

“It’s absolutely too hard to do for small growers,” he said.

The group, which started as a spin-off the Washington Farm Bureau, brings about three-fourths of the H-2A workers to Washington under contract for growers.

The agency has begun flying small groups of workers from Mexico and El Salvador to Washington orchards this year, though most still take a bus.

In Washington, labor consultants and officials expect more than 15,000 H-2A workers this year.

Earlier start dates, more chores

In spite of the imperfections, not only are growers bringing more foreign guest-workers across the border, they’re hiring earlier.

Washington state’s employment agency received more than 140 applications for nearly 13,000 workers by the end of March.

H-2A laws generally limit contracts to 10 months, with a few exceptions.

That means H-2A workers are doing a broader diversity of duties than just seasonal picking.

Pruning, planting, thinning, sprayer maintenance, tractor driving and even supervising are on some federal work orders this year.

Second-year H-2A employee Omar Campos, 32, is working as a spray application tractor driver at a Stemilt Growers ranch near Quincy, Washington, on a nine-month contract.

He sends most of his money home to support his family in the central Mexican city of Guanajuato, but he also is learning new skills, he said.

The variety of tasks are allowed under H-2A rules, as long as those job duties are listed on the contract with the state Department of Labor, something attorneys and labor consultants urgently and frequently remind their clients.

Ric Valicoff, a Wapato, Washington, grower who hires H-2A workers, plans to start in the winter in the future. He would have liked 30 to 50 more workers this year for pruning, planting and tending his nursery, but his new, 92-bed facility wasn’t ready in time.

He will have to rent from an apartment complex in nearby Yakima for one more year.

A total of 85 countries are eligible to send H-2A workers to the United States, but the vast majority come from Mexico.

Guatemala is second, while Jamaica — which sends most of its workers to the East Coast — is third.

Growers who use H-2A year after year typically swear by the results and sing the praises of their visiting employees’ work ethic. Some of the H-2A workers at Mt. Adams Orchards in Bingen, Washington, have been coming back for 11 straight years. Managers even store the workers’ gear for them.

“H-2A is very doable,” said Troy Frostad, who manages the company’s visa program, started in 2006 after the company left about 1,100 bins of fruit on the trees due to a severe shortage of labor. Today, they have 200 H-2A workers spread out over three different contracts.

First step is the hardest

H-2A is neither cheap nor easy.

John Teeple, a Wolcott, New York, apple grower, estimates he pays close to $1,200 per person for transportation and fees alone to hire between 30 and 40 H-2A workers to help harvest his 350-acres for the past six to eight years.

“People think we get H-2A labor because it’s cheap labor,” Teeple said. “It’s very expensive labor.”

In Royal City, Washington, orchardist Dain Craver estimates his production costs have doubled, from $5,000 to $10,000 per acre, since turning to H-2A labor.

Housing is one of the biggest, most expensive hurdles. Growers are required to provide housing for no cost, either renting rooms or building their own dormitories at a cost of more than $10,000 per worker.

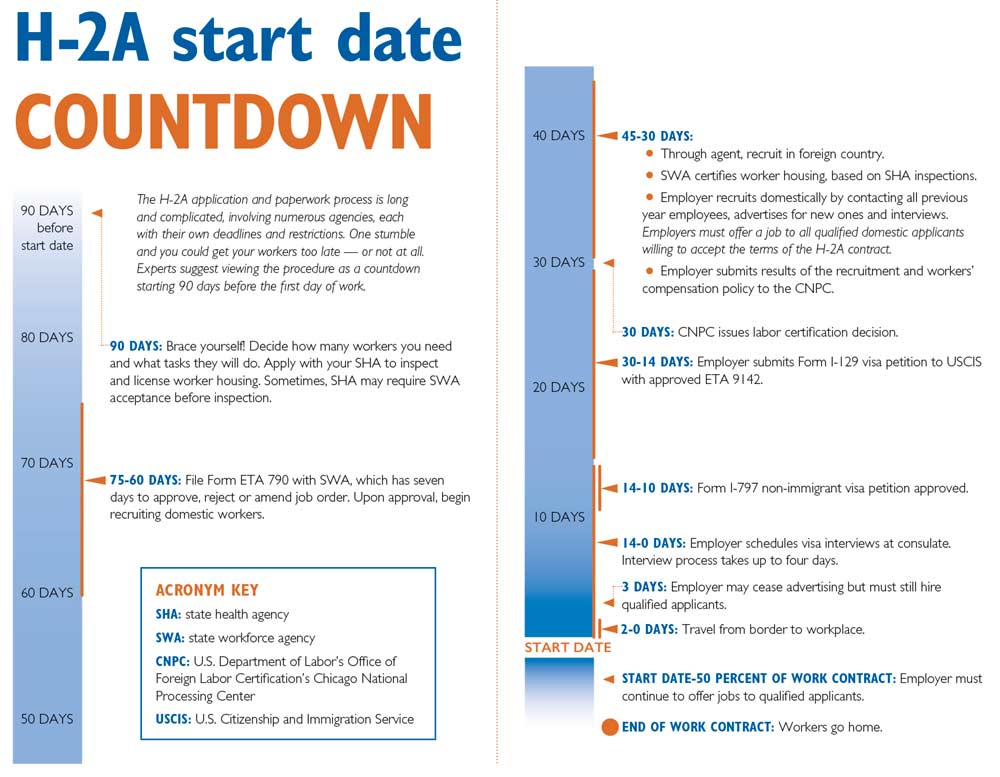

The paperwork alone is arduous. The application involves a 75-day administrative process with tight deadlines and a host of restrictions from both state and federal agencies.

Tripping over any of them could result in delays getting worker visas, rejection of the application or lawsuits.

In February, Mercer Canyons of Alderdale, Washington, settled a lawsuit for $1.2 million after two resident workers alleged they were not told about job opportunities filled by H-2A workers in 2013.

The primary and central condition for hiring H-2A workers is to demonstrate — “prove” in Gempler’s terms — a lack of available domestic employees. “The premise of this program is that Americans get first shot at these jobs,” Gempler said.

He and other consultants recommend making sure everybody in a farming company, not just those who handle human resources, know that. All it takes for an expensive legal challenge is for one local to idly ask about work from say, a foreman on a tractor, who gives an answer such as, “Nope. We have workers from Mexico this year.”

Frustrations

New York grower Chip Bailey is in his second round of H-2A labor after throwing up his hands in frustration a few years ago.

For about five years, Bailey contracted H-2A workers from Jamaica to help harvest his 200 acres of apples in Williamson. “It went very smooth the first five years we were in it,” he said.

However, in 2013, the Department of Labor implemented some changes that restricted how much experience he was allowed to require on job applications.

The dispute went to a Washington, D.C., arbitration judge, and he called his U.S. congressman for assistance before the opposing lawyer dropped the case. By then, it was too late in August, so he cancelled his order and scraped by with domestic workers.

Last year, driven by an even greater labor crunch, Bailey started up again. His contract was approved, but he hobbled along with domestic workers and never needed to fill it.

This year, he plans to go all the way. One supervisor arrived in March. A crew of 20 more, all from Mexico this time, will arrive in August to join his 10 domestic employees for harvest.

“The program is imperfect, but I don’t see another option,” he said. “I don’t a see politician moving on a better option. This is the hand we’re dealt. We better learn how to play it.”

Another risk is the potential psychological toll on domestic workers, some of whom may have been loyal to their employers for decades. Many H-2A employers take extra measures to reassure their local employees that the guest workers don’t pose a threat to their jobs. After all, replacing them would be against the law.

“There was fear on their part,” said Tim Welsh of Columbia Fruit Packers, who said he has a pool of loyal employees from the Mattawa, Washington, area. He found himself visiting the company’s shops personally to assuage their concerns, something he doesn’t often do.

“They do look for the leadership to step in and give them assurance,” he said. “So I probably stepped in a little bit more than I want to do.”

A wild card

One wrinkle may slow H-2A growth: the allure of mechanization.

A few growers using H-2A were tempted to expand this year but are holding off to see the automated harvesters in development will ease their seasonal labor crunch in the next two or three years.

Guest workers comprise between 30 percent and 40 percent of Columbia Fruit’s workforce in certain orchards, representing a steady increase over the company’s five years in the program.

Welsh considered increasing again this year, but held off because the company would have had to expand its housing facilities.

Jim Doornink, a Wapato, Washington, grower, would like more employees, he said, but always manages to squeak by with enough domestic workers for his 250 acres, spreading out his chores to keep his 15 year-round employees as busy as possible.

However, he has been preparing his staff for H-2A if the need gets great enough, knowing the first year is the hardest.

“We go to the H-2A seminars every year …” he said. “We try to be educated, so that if we have to do it we’re not completely cold on the spin up.” •

H-2A tips

Tips and advice for growers using H-2A labor could fill a book, but here are a few highlights discussed during workshops and conferences this year:

—Put a variety of farm tasks on the DOL contract and stick to them. Don’t allow H-2A workers to stray from that list.

—Leave some beds empty. If domestic workers from outside the area show up and join your crew, they may be entitled to housing.

—Document every interaction related to employment, even seemingly informal ones. Steer all applicants or those inquiring about jobs to a central office where staff members can document their inquiries.

—Think 90 days ahead. The administrative paperwork between state employment agencies and the DOL takes time and requires numerous deadlines.

—Establish communication with local banks and grocery stores where you plan to take those workers once they arrive. Part of the requirements is providing them transportation to stores.

—Forbid anyone in the pipeline from charging fees to the incoming workers. Check with them when they arrive.

—Talk to an insurance company about coverage during the trip and in their housing facilities.

The housing question

If you are considering contract guest workers under the H-2A visa program, “you need to ask yourself where they all will live,” said Kerry Scott of Mas Labor, the nation’s largest H-2A placement agency.

Federal law requires growers to offer free housing to their guest workers either by renting apartments, hotel rooms or building on-site dormitories. What’s more, whatever you offer H-2A workers, you have to offer domestic workers who travel a long distance to work. That exact distance is nebulous.

Building on-farm housing for H-2A workers typically runs between $10,000 and $15,000 per worker.

Growers are allowed some creativity, but the facilities must be inspected and licensed by a state health agency before the federal Department of Labor will approve the H-2A contract application. That review itself can add to an already lengthy process.

Styles vary. Some are low-slung apartments arranged around a grass courtyard. Other growers use trailers. Scott knows of farmers using surplus FEMA trailers in Louisiana. Orchardist René Garcia in Tieton, Washington, renovated two old farmhouses, one with a capacity of 40 beds, the other 30.

Tents are not allowed.

Smaller growers, or those not using many H-2A workers, sometimes rent apartments or hotel rooms in nearby cities. Or, they contract with an agricultural labor nonprofit such as the Washington Growers League or Wafla.

The Growers League, based in Yakima, Washington, has ag workforce housing dormitories in Cashmere and Malaga and will begin construction on a new one in June in Mattawa. Wafla, based in Lacey, owns a housing facility in Mesa and is building a new one in Okanagan.

Scott has heard of smaller growers teaming up on an H-2A contract, largely to spread out the housing costs. His company has represented up to six or seven growers on one contract. It works well when the harvest of a specific crop typically progresses over time across a geographic area, such as following a river valley uphill.

“You need to trust your neighbor,” Scott said.

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment