Planting with certified, “clean” plant material is the first line of defense against grapevine viruses. But research funded by the Washington wine industry shows that growers need more than just “clean” for vineyard health, longevity and profitability.

Washington wine industry’s rapid expansion during the past 15 years, combined with a shortage of certified grape plant material and limited diagnostic technology, has resulted in disease creep throughout the state.

Grapevine leafroll disease, the most prevalent of grapevine viruses in the world, is also the most prevalent viral disease in Washington.

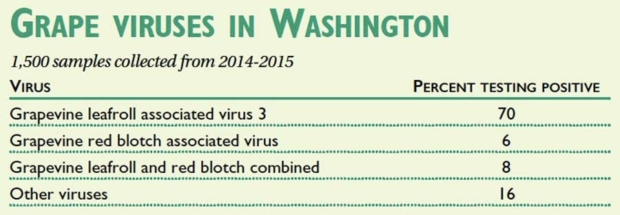

Of nearly 1,500 samples collected throughout the state during the last two years from red and white wine grape varieties, around 70 percent tested positive for grapevine leafroll associated virus 3. (Read “Grape viruses in Washington,” May 14, 2014, Good Fruit Grower).

Close to 6 percent were positive for grapevine red blotch associated virus, 8 percent had a combination of leafroll and red blotch viruses and 16 percent were negative for leafroll and red blotch, but positive for other viruses.

Samples were taken based on visual virus symptoms for red varieties, but random samples were taken for whites because whites don’t show symptoms.

Grapevine viral diseases are especially challenging. Visual symptoms that show in the leaves can be confused with other factors (mechanical injury, nutritional imbalance, heat or environment stress), and different vectors are involved in virus spread.

Mealybug insects and scale are known vectors of leafroll disease, while the three cornered alfalfa treehopper was recently identified as another possible vector of red blotch disease. Viruses can also be spread through propagation.

A universal issue among grape viruses is that there’s no existing cure for what can result in significantly reduced yields, fruit quality and vineyard longevity.

A published Washington State University study on the impacts of leafroll disease on fruit yield and grape and wine chemistry found that wines from leafroll-affected, own-rooted Merlot grapes had significantly lower alcohol, tannins and anthocyanins compared with unaffected, own-rooted Merlot grapes made into wine from the same vineyard.

It was previously reported in Good Fruit Grower (March 15, 2015) that a grower can lose up to $20,000 per acre over a 20-year period depending on the extent of crop loss and level of decline in fruit quality, according to a WSU economic study.

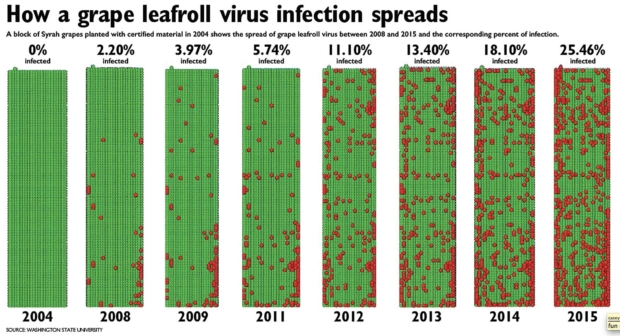

Recent research funded by the Washington State Wine Commission shows how quickly a young, clean vineyard can become infected from nearby diseased vines. Further, the study highlights the importance — especially in the early years of a vineyard — of constant vigilance and rapid response.

High priority

For more than a decade, Washington’s wine industry has supported the work of Naidu Rayapati, Ph.D., WSU plant pathologist and interim director of the Clean Plant Center-Northwest.

Rayapati has worked with growers and state agricultural officials to survey vineyards and grape nurseries in the state for diseases that include leafroll, the recently discovered red blotch and others, and to develop strategies to strengthen the state’s certified grape plant program.

As a result, mother blocks are now inspected three times per year by the Washington State Agriculture Department. Also, because visual inspection is not always reliable, diagnostic testing of mother blocks has been adopted as an assurance for maintaining clean plants in nurseries.

Rayapati’s team of six WSU graduate students and post-doctorates are working to reduce the costs of diagnostic testing by developing a single test that detects both leafroll and red blotch and develop post management strategies to help growers manage viral diseases.

Rayapati’s research is primarily funded by the Washington wine industry, but his program has been greatly leveraged with supplemental funding from a variety of resources, including the Washington State Commission on Pesticide Registration, the Northwest Center for Small Fruits Research, and state and federal specialty crop grants.

This leverage allows Washington’s wine industry to receive the greatest bang for its research investment.

Of late, Rayapati is studying the pathways of virus spread into newly planted, clean vineyards as well as cultivar and site-specific impacts of viruses on vine performance.

Spread in young vineyards

The industry mantra is still to use certified plant material or to test bud wood before planting, Rayapati said. “But this strategy alone is not good enough because there is always the risk of viruses spreading into young vineyards from infected neighboring vineyards,” he said.

Rayapati’s team has compiled a detailed picture of how leafroll disease spreads in young vineyards planted with clean plant material.

They studied three vineyards in different locations that were planted with certified plant material of Cabernet Sauvignon, Syrah and Petite Syrah in 2004, 2007 and 2009, respectively.

All three blocks were in close proximity to old blocks that were heavily infected with leafroll disease.

Vines in the new vineyards were monitored for disease up to the 2015 season. Symptomatic vines of the three vineyards were tested for leafroll disease, along with immediately adjacent vines, even those not showing symptoms.

The locations of infected vines were plotted on a matrix and a map of the spatial data was evaluated for disease spread.

Not surprisingly, vines showing symptoms in the early years of the three vineyards initially occurred in rows closest to the heavily infected blocks and declined as distance from the infected blocks increased.

This “edge effect” indicates that leafroll spread is occurring from the infected blocks into the newly planted vineyards, explained Rayapati.

“But in subsequent years, the spatial distribution of symptomatic vines showed aggregation or clustering,” he said. “This clustering indicates a secondary spread of virus between adjacent vines within a row and across adjacent rows as a consequence of vine-to-vine movement of vectors around the primary site of infection established in young blocks.”

Rayapati also found site-specific factors are involved in spread of disease. In one location, wind led to an increased dispersal of vectors and an increase in the rate of disease spread in the young vineyard.

Management strategies

“Planting clean material is only the beginning step in managing diseases,” he said.

“Never assume that cuttings used in propagation are clean from disease — unless they are from a certified source,” said Rayapati, who added that more than 25 percent of cuttings and bud wood samples brought to his lab by growers for testing were infected with viral diseases.

Once vines are planted, it’s critical to monitor them closely the first few years.

“And, if symptomatic vines are noticed, quick action is needed,” he said.

That includes testing symptomatic and nearby asymptomatic vines, and if virus is present, removing (rogueing) the infected vines quickly to prevent further, secondary spread. Growers can bring samples for testing to Rayapati’s lab at WSU’s Irrigated Agriculture Research and Extension Center in Prosser, Washington.

ONLINE

Rayapati’s recently published research on the impacts of leafroll disease on fruit yield and grape and wine chemistry is archived on the Washington State Wine Commission’s website at washingtonwine.org/research/reports.

– by Melissa Hansen, a research program manager for the Washington State Wine Commission.

Soil-borne viruses in WA vineyards

Samples include red and white wine grape varieties collected from throughout eastern Washington. Samples for red varieties were taken based on visual virus symptoms but were randomly collected for white varieties. Source: Washington State University

Two soil-borne viruses affecting grapevines were recently confirmed in Washington wine grape vineyards, reported Naidu Rayapati, Washington State University plant pathologist.

Tobacco ringspot virus has been confirmed in Grenache and Tempranillo vineyards in Washington’s Yakima Valley, and grapevine fanleaf virus was found in Cabernet Franc, Chardonnay and Pinot Noir blocks in Yakima Valley and in Cabernet Franc blocks in Walla Walla Valley.

Fortunately, the dagger nematode species (Xiphinema index) that transmits grapevine fanleaf virus is not currently present in Washington soils, therefore, removing infected vines would eliminate the risk of fanleaf, according to Rayapati.

However, Tobacco ringspot, another soil-borne virus, is spread by the dagger nematode species found in Washington soils, and management of tobacco ringspot will involve clean plants and nematode suppression strategies.

The symptomatic Grenache vines showed severe stunting and decline symptoms and poor fruit set, he said.

The pathogen resides in the soil and can be a problem when grapes follow tree fruit crops like apples and pears.

In this case, the virus did not have any impact on pears that were planted before the vineyard, but caused devastation in the wine grapes.

Sampling of soil near the symptomatic Grenache vines showed dagger nematode (Xiphinema rivesi) was the predominant nematode species.

Further experiments using virus-free Cabernet Franc vines and cucumber seedlings planted near the symptomatic Grenache vines as bait showed that the dagger nematode can transmit tobacco ringspot virus.

“This is a classic example of a virus “jumping” from one crop to another and serves as a learning experience for growers to keep in mind the crop history before planting wine grapes because some viruses may be a more serious problem to grapevines than to other crops,” Rayapati said.

Leave A Comment