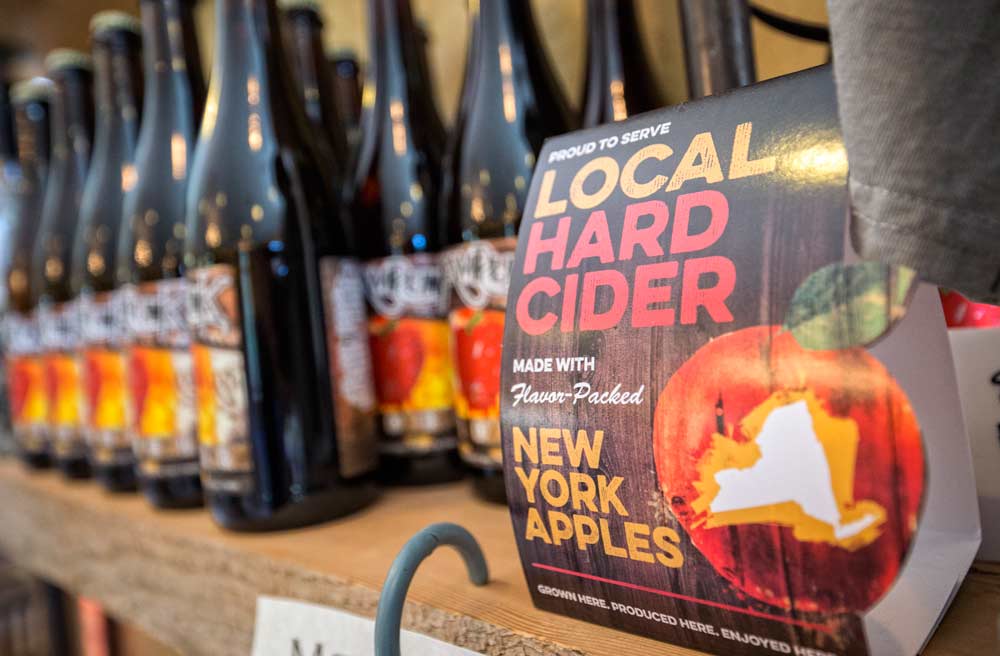

Bottles of cider are displayed at Leonard Oakes Estate Winery in Lyndonville, New York, along with an ad marketing a sense of regional flavor. Experts suggest apple growers embrace their regional differences to capitalize on the surging growth of the market the same way grape growers market wines tied to the complex terroir of different regions in the wine industry. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

Google the phrase “The Napa Valley of Hard Cider.”

Turns out, a lot of places, including southwest Michigan, New York’s Hudson Valley and various locales in New England, are gunning for the title.

However, experts advise growers interested in producing apples to fuel the hard cider market’s rapid growth to look beyond the hype and do homework before investing.

“The important thing is to talk to the cideries,” said Greg Peck, a Cornell University horticulturist and one of the nation’s few researchers specializing in hard apple cider.

Ask them what varieties they want and then make sure they will grow in your area.

Regionalization

About that phrase: “The Napa Valley of Hard Cider.”

It’s been tossed around in general news magazines and a few grower conferences to describe efforts to make hard cider a calling card for tourism and sales.

But in reality, the surging cider trade is showing more nuanced signs of regionalization with each area developing its own flavor, much like the varied terroir of the wine industry.

“And that’s a good thing,” said Dale Brown, managing partner of the Cyder Market, an Alexandria, Virginia, firm that operates a cider industry news and information web portal.

New England is becoming known for sharp-tasting ciders, while some Michigan cider makers use the Midwest staple McIntosh, in spite of naysayers who insist on cider-specific, high-tannin varieties. “But they do it and they do it very well,” Brown said.

Then again, some companies are experimenting with infusing cider with everything from habañero peppers to cherry juice.

There’s room in the cider race for all apple-growing areas, he said.

While the cider market growth overall has slowed recently, the craft segment — much like craft beer — is still surging. New cidery starts in the United States have averaged 129 per year over the past three years.

If growers plant the right apples, they will be able to sell them for $15, $20, $25 a box and higher, rivaling the prices of fresh-packed dessert apples, even in three of four more years, he predicted. “There’s room for growth, if you will.”

Growing the apples

Greg Peck

In the cider world, Peck is best known for his work analyzing cider-specific varieties — apples high in tannins that create the complex flavors of cider but make you gag if you bit one raw.

Peck encourages growers to embrace regionalism while he and fellow researchers continue to seek more information about varieties, rootstocks and growing techniques. He admits there’s still a lot for everyone to learn.

“There’s been a void of data … to make recommendations for growers,” Peck said.

In the meantime, he suggests working with land grant universities to seek local tips. Several have websites dedicated to local cider resources and information.

As for growing techniques, opinions vary.

Steve Wood, who owns Farnum Hill Ciders in Lebanon, New Hampshire, recommends growers back off the density and return to larger trees, letting cider apples ripen until they fall to a grassy ground cover on their own, the way it’s done by traditional growers in England. If growers use a weed-free strip to start their trees, cover it once production starts, he said.

“The advice point is suck it up and pick them up off the ground and get rid of your weed-free strip,” said Wood, one of the better-known cider producers in the country.

Some traditionalists, pointing to America’s colonial history, subscribe to his ideas, while others are planting cider-specific varieties in high-density orchards with narrow canopies , ready for mechanical harvest in a few years.

“There’s a real Old World versus New World debate,” said Alan Leonard of Cummins Nursery in Ithaca, New York.

Leonard and Peck suggested growers stick with the orchard management system they already know. If they are more familiar with two-dimensional fruiting walls or trellises, there’s no reason to change.

Peck’s research team has current projects exploring how orchard structure and harvest relates to cider apple quality but suspects they will find similar results to those of culinary apples that thrive on the even sunlight exposure of modern orchard systems.

Also, grafting speeds up production, Peck said. Cider-specific variety trees are in short supply with growers ordering two years out.

Dave Rosenberger, one of Peck’s retired Cornell colleagues, writes that growers may top-work cider-specific varieties onto existing roots, though Peck warns growers to use virus-resistant rootstocks if they come across suspect scion wood.

“It can be quite polarizing,” Peck said. “There’s a lot of different ways to grow this kind of fruit.” •

ONLINE

Find links to university websites with information about cider for growers at goodfruit.com/resources

– by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment