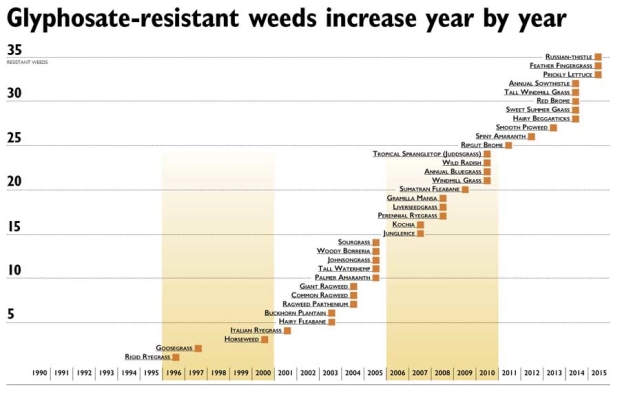

CLICK TO ENLARGE (PDF) The longer a herbicide is on the market, the longer the list of resistant species. There are 35 known Roundup-resistant weed species in the world. Source: Ian Heap, WeedScience.org (Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower illustration)

Grape growers tend to base weed control choices on what they used successfully in the year of their best yields.

They may vary those choices somewhat to account for specific problems their scouts turn up, but usually there are two or three compounds they use year after year.

Instead of finding continued success and high yields, those “tried-and-true” weed control compounds are bringing two other things to vineyards: herbicide-resistant and herbicide-tolerant weeds.

When weeds are suppressed but not controlled — plants are partially wilted, for example — it usually means the weeds are naturally less sensitive to a control measure or herbicide-tolerant.

Herbicide resistance, meanwhile, is a plant’s inherited ability to survive following exposure; resistance may be naturally occurring or a result of genetic engineering. Over time, the few resistant plants can multiply into a much larger population.

It’s a natural process, virtually the same as drug resistance. The longer a herbicide is on the market, the longer the list of resistant weeds.

For example, according to the International Survey of Herbicide Resistant Weeds, there are 35 known weeds resistant to Roundup (glyphosate). The site also reports 11 herbicide-resistant weeds found specifically in vineyards.

Tolerant and resistant species can develop in a vineyard in one region of the country and find their way to others hundreds of miles away.

“Some seed, like horseweed/marestail, can fly very far,” Dr. Andy Senesac, Cornell University/Long Island Extension weed specialist, said at the Mid-Atlantic Fruit and Vegetable Convention in Hershey, Pennsylvania, this winter.

The best protection against resistance is to monitor vineyards after treatment. “If a post-emergent was used, look for a single, slightly injured or uninjured weed species,” Senesac said. “With pre-emergents, watch for a single species appearing soon after application.”

Late summer is prime time for spotting resistant species, Senesac said. Growers should look for the sudden appearance of a weed that has been controlled for years; annuals with a high level of seed production should top the list.

Horseweed/marestail

Mother Nature designed horseweed, also known as marestail, to take to the air and fly long distances.

It’s this ability that makes horseweed a distinctive threat. The other reason: This annual broadleaf is Roundup-resistant.

Roundup-resistant horseweed biotypes developed in no-till, Roundup-ready corn 15 years ago. Seed spread is so widely dispersed, Senesac said, they are now scattered throughout the Midwest and Northeast. Each horseweed plant can produce 10,000 to 250,000 seeds.

Roundup cannot control the weed’s fall-emerging seed rosettes. There isn’t a good pre-emergence option — even though there are several effective control products — because the main germination flush does not begin until late summer, making these products impractical or unpermitted, Senesac said.

In the Pacific Northwest, growers looking to control horseweed in new vineyard plantings are limited to Trellis (isoxaben) or Goal (oxyfluorfen) as treatments before horseweed emerges and to glyphosate after the weed begins to show, according to Dr. Drew Lyon of Washington State University’s Department of Crop and Soil Sciences.

In established plantings, Northwest growers have a list of compounds they can try pre-emergence: Karmex (diuron) and similar brands, Alion (indaziflam), Solicam (norflurazon) and Princep (simazine).

Post-emergent applications include Aim EC (carfentrazone), Rely (glufosinate), Roundup, Venue (pyraflufen) and Gramoxone Inteon (paraquat), Lyon said.

Several other products provide pre- and post-emergent control of horseweed in established plantings.

These include Chateau (flumioxazin), Goal and Matrix (rimsulfuron). Alion and Matrix can be tank-mixed to provide pre- and post-emergence control as well.

Northeast growers looking to control seed spread should try a post-emergent application of Rely or Aim EC, Senesac said. Contact herbicides like Gramoxone are also an option.

But Senesac said he’s found that the best means to control horseweed is Alion, the relatively new herbicide introduced to the market in 2013. It can be used on grapevines established five or more years.

Alion inhibits cellulose biosynthesis, preventing cell walls from forming in plants, disrupting seedling development. It has very low volatility and low leaching potential.

“It can be applied anytime of the year on unfrozen soil,” he said. “Its plant-harvest interval is 14 days.”

Senesac said there are two reasons growers should consider using the compound.

One is the environmental load necessary to achieve control is very low; its application rate is 3.5 to 5 ounces per acre or .045 to .065 pounds per acre-inch. “That’s the equivalent weight of four to six nickels,” he said.

The second reason is its staying power. “It has the potential to remain active with a spring application long enough to inhibit horseweed seed germination into late summer and beyond,” Senesac said.

Organic growers, meanwhile, can use Scythe (pelargonic acid) or Suppress (caprylic and capric acids), which is labeled for most food crops, including grapes. Senesac plans to run trials on Suppress this summer.

Field trial

In response to grower concern about Alion’s effect on between-row cover crops, Senesac conducted a field trial.

He seeded several field-grown ornamental plots with buckwheat 13 months after an Alion and Chateau (flumioxazin) application.

At 2.8 fluid ounces, a rate just below the labeled grape rate, and six weeks after seeding, 58 percent of the cover remained. At 8 ounces per acre, Chateau left 54 percent of the cover crop.

“Neither prevented adequate establishment of buckwheat,” Senesac said.

At lower rates, growers should not experience problems planting cover crops the following year, he said, though applying the compound at higher rates may prove otherwise. •

– by Dave Weinstock

Leave A Comment