An apple orchard grows on a terraced hillside in northern India’s Himachal Pradesh state, where individual growers, governments and the World Bank are investing to modernize the fruit industry with high-density plantings and sophisticated postharvest tools. (Courtesy Kunaal Chauhan)

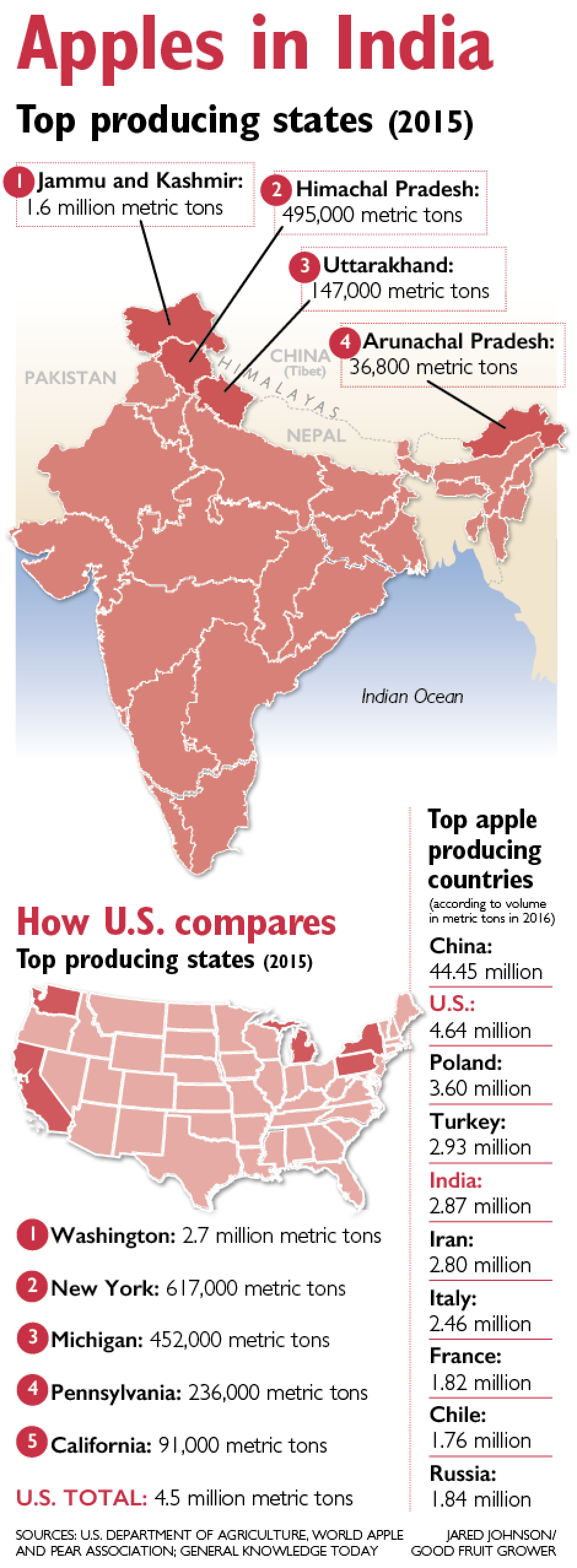

A tree fruit renaissance is underway in India, the world’s fifth-largest apple producer.

Long a region of traditional Red Delicious orchards high in the eaves of the Himalayan Mountains, the nation’s growers are moving toward Italian varieties with high-density plantings on dwarfing rootstocks.

Funded by individual growers, provincial governments and no-less than the World Bank, the work is driven by India’s growing economy and climate change pushing quality production uphill.

Funded by individual growers, provincial governments and no-less than the World Bank, the work is driven by India’s growing economy and climate change pushing quality production uphill.

“If we don’t change ourselves with new varieties, the lower regions will not have any apples,” said Dixit Chauhan, whose family grows 20 acres of apples in Himachal Pradesh, India’s second-largest producing state.

Highlighting the investment in India is a 2016 $135 million loan from the World Bank to modernize the tree fruit industry in Himachal Pradesh.

The money will pay for a host of items, including new trees, rootstocks, hydrocoolers, trellis structures, packing house machinery, storage facilities and even landscaping flowers surrounding a new research center in Shimla, a rural community near the center of the growing region.

Apples are the most prominent fruit, but the money also will fund development for pears, stone fruits and berries.

Growers will receive the bulk of the new plants this winter when 800,000 to 900,000 trees are scheduled to be distributed, said Kunaal Chauhan, an apple orchardist in Shimla. Up until now, growers have been receiving 10 to 20 trees each, not nearly enough to boost high-density acreage.

“The project is proposed to revamp the horticultural practices and in short the whole industry here,” said Kunaal Chauhan, who is a friend of Dixit’s but no relation.

In neighboring Jammu and Kashmir, the top-producing state, the provincial government began offering subsidies last year for replanting new varieties in higher densities, attempting to boost yields by three or four times, according to reports in Indian newspapers.

History

In recent years, India has fluctuated between the fifth- and sixth-largest apple producing country in the world, according to statistics from the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the World Apple and Pear Association, with the northern states of Kashmir and Himachal accounting for nearly the entire market share.

Apples have a long history there.

Texts of ancient travelers about Kashmir mention apples and other temperate tree fruits, while writings of emperors in the 1400s discuss grafting apples with imported bud wood. British military officers tried starting orchards of sour English imports in the late 1800s.

Apple cultivation as a commercial crop started in India in the early 20th century when a Philadelphian named Samuel Evan Strokes joined a leprosy mission and began importing Red Delicious and Golden Delicious saplings in Thaneder, a small mountain trail town in Himachal Pradesh where he settled with his Indian wife.

In both states, apples are grown on steep terraced slopes of the Himalayan foothills, ranging in elevation from 4,500 feet to 12,000 feet, and irrigated with rainfall or glacier runoff.

Orchards are typically small; Himachal’s average is 3 acres. Most growers pack by hand in small on-farm packing sheds and truck their boxes to local auction yards.

It all paints a quaint, rural picture.

But India’s middle class is growing and demanding more fresh fruit, more than the domestic growers can supply with traditional orchard designs, limited controlled-atmosphere storage facilities and poor roads.

Thus, stores in the south find it more economical to import apples than ship them across the country, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Apples are India’s most imported fruit.

For 10 years or so, Indian energy companies Adani and Reliance have started their own produce brands and stores and have been purchasing directly from farms.

Meanwhile, researchers have been planting apple trees in the tropical state of Karnataka where they believe they can coax two crops a year from the trees.

Growers aren’t waiting

In many places, growers are not waiting for World Bank funds to begin planting trellised, high-density orchards on dwarfing rootstocks, like this orchard in Himachal Pradesh. (Courtesy Kunaal Chauhan)

Growers in Himchal or Kashmir haven’t been waiting for the World Bank money. Some have been boosting their densities for more than a decade, converting Malling rootstocks with smaller trees sometimes covered with hail nets. Many of them send notes to the Good Fruit Grower asking for rootstock advice.

Dixit Chauhan and his extended family are among the early adopters. With their own money, they have been converting their acreage to new varieties with high-density plantings, using roots such as Malling 7, 9, 106, 111 and 116. “It’s outdated to you in the U.S.”

After two generations of Red Delicious and Golden Delicious, they now have between 5 and 10 acres of Red Chief, Scarlett, Oregon Spur, Red Block and Galas.

“Galas are also getting famous here now,” he said. (Galas are now the No. 1 apple by volume in Washington, America’s top-producing state.)

Many of his neighbors are slow to change though, fearing they will lose too much income over the short term by cutting down old trees. That’s especially true for older growers with smaller parcels.

“Only the new generation is doing this thing,” Dixit Chauhan said.

An apple orchard perches on the edge of a cliff above the Satluj River in Himachal Pradesh. (Courtesy Kunaal Chauhan)

In 2012, the mechanical engineer left a steady job at Dabur India, a company specializing in holistic Ayurvedic and natural medicinal products, to return to his family orchard, fearing it would have gone out of business otherwise. He is now 36 and married with two daughters.

Kunaal Chauhan, 30, has a similar story. He grew up on the orchard but left his Dell Computers job in 2010 to return to the farm and help care for his ailing parents.

He manages the family’s 13-acre orchard in Kotkhai, which he calls the “Wenatchee” of Himachal (referring to Wenatchee, Washington), with his father and grandfather, now 97 but still involved. He has visited orchards in the United States and Italy and has been trying to adopt some of the modern techniques at home.

“More and more growers are moving to high-density plantations, with high-colored strains of Delicious and Gala as popular plantation choices,” he said. “Our cost of production is much lower than other countries, and we have close to 70 percent profit on returns, so apple growing is a profitable business currently.”

Workers sort apples by hand in Lokinder Bisht’s on-farm packing line in Himachal Pradesh. About 90 percent of the fruit in the state is graded by hand, but basic mechanical grading is becoming more popular. (Courtesy Lokinder Bisht)

Lokinder Bisht is a third-generation farmer growing apples at two elevations. At his lower site — 5,072 feet, where harvest starts in July — he is gradually replacing spur types such as Red Chief and Scarlet with Galas, as well as Redvelox and King Roat, which are both high-color Italian strains of Red Delicious. At his 8,257-foot orchard, he has Red Delicious and Golden Delicious on traditional seedling stock but is converting to Granny Smith and Fuji.

He was one of the first people to use clonal rootstocks in 2003 and today has about 5,000 trees in medium-density plantings on 35 acres, he said.

Redvelox apples, a new Italian strain of Red Delicious, grow in an orchard in Himachal Pradesh, long a home to more traditional varieties and strains. (Courtesy Kunaal Chauhan)

He also is taking moderate steps toward some mechanization, though platforms are prohibitively expensive and nearly impossible to use on steep terrain. However, he and other growers have tried two-wheeled “mini-tractors,” brush cutters and mechanized grading on sorting lines.

Dixit Chauhan, Kunaal Chauhan and Bisht all are officers in the Progressive Grower’s Association cooperative, formed in 2014. Most of its 171 members have taken strides to modernize.

The group stages educational workshops and tours for growers and hosts visiting apple experts from the West. The change will continue step by step in the future, borrowing ideas from Europe and North America.

“In the future, we intend to move completely to high- and ultra-high-density plantations, focusing on high-color strains and quality, to be able to sustain ourselves in the face of better quality imports of apples,” Bisht said. •

—by Ross Courtney

A 5-year-old medium-density block of Scarlet and Oregon spurs grow on Malling 111 rootstock, with plantings 5 feet between trees and 7 or 8 feet between rows on Bisht’s farm. (Courtesy Lokinder Bisht)

Very well written by the author.