In the pollination and crop load management session of the Washington State Tree Fruit Association’s Annual Meeting Tuesday afternoon, Washington State University’s Matt Whiting discussed the variability of cherry fruit set, year to year, site to site, tree to tree and even limb to limb.

His research data from Prosser experiment blocks showed fruit set variability between 0 percent and 100 percent in some cases.

“I’m going to predict that variability will increase over time,” Whiting said.

Whiting is working on a mechanical pollination system that uses an electrostatic sprayer that will establish more consistency than letting pollinators visit pollinizers, a method of fertilization that hasn’t changed since humans first domesticated fruit thousands of years ago.

Also in the session, WSU’s Stefano Musacchi idly suggested exploring compatibility of pollinizers for pears, much the same way he has for apples. It might be even more important, he said.

He has no serious proposals in the works, he said, but commercial pear cultivars and commonly used pollinizers share many of the same S-alleles, making them incompatible or partially incompatible with the target cultivars, he said. Meanwhile, bees are not attracted to all pear varieties and pollinizers equally.

After a fungal disease in Manchurian crab apples led to an apple quarantine by China in 2012, Musacchi researched dozens of alternative pollinizers and winnowed the list down to six Malus strains — Malus 2, Malus 3, Malus 15, Malus 17, Malus 18 and Malus 33 — that are most compatible in timing and pollen alleles with many of Washington’s common apple cultivars. An Oregon nursery is continuing to evaluate them.

Also, Musacchi recommended Snowdrift, Indian Summer and Mt. Evereste as pollinizers for the WA 38.

The session also included presentations on native pollinators, fruit set models and precision timing of fruit set and thinning.

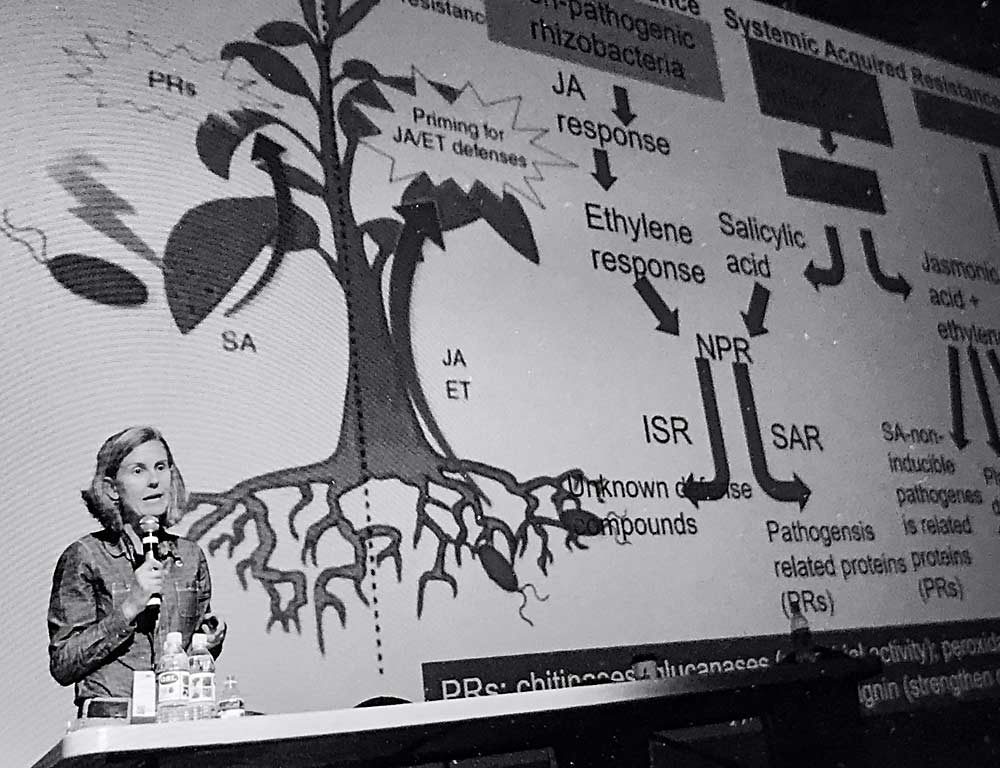

In the pathology session, there was good news and bad news. The good: 2019 saw much lower fire blight pressure throughout the Pacific Northwest than in 2017 and 2018. WSU Extension specialist Tianna DuPont joked that she knew this year was better for fire blight because attendance at the session wasn’t as packed as the standing-room-only presentation she gave last year.

But there is still at a lot of inoculum out in the environment, she said, encouraging everyone to continue to be aggressive in cutting out strikes and cankers to reduce pressure for next year.

To improve control, DuPont recommended that both conventional and organic management programs extend coverage past petal fall, since those typically warmer days can pose a risk even though only straggling blooms remain. She also recommended that conventional growers consider using Blossom Protect at bloom as a preventative.

“It’s going to be out there, doing its job, before the risk window,” she said. She also shared results of ongoing research into using Apogee (prohexidione calcium) to reduce fire blight, which has shown great promise in New York. The timing appears to need adjusting in the Northwest, since flowers progress from pink to bloom much faster than in the East.

The bad news: Little cherry symptoms have spread significantly across the Pacific Northwest. Last year, WSU pathologist Scott Harper warned the industry that the pathogens responsible for the unmarketable fruit were heading toward epidemic growth.

“Unfortunately, I was right,” Harper said. About half the samples sent to his lab this year have tested positive for the X phytoplasma — one of the pathogens —up from 24 percent last year. “I don’t want to take a guess at next year, but it’s not going to be pretty,” he said.

Leafhoppers act as a vector for the X phytoplasma, especially later in the season after harvest, so growers should adopt vector control programs from harvest until late fall, said WSU entomologist Tobin Northfield.

But insect management alone can’t solve the problem: The imperative is to remove infected trees as soon as possible so there is less disease for the insects to spread.

—by Ross Courtney and Kate Prengaman

Related:

—X disease devastation strikes Pacific Northwest

—Managing fire blight for the conventional grower

—A better bee? Blue orchard bees show promise as pollinators

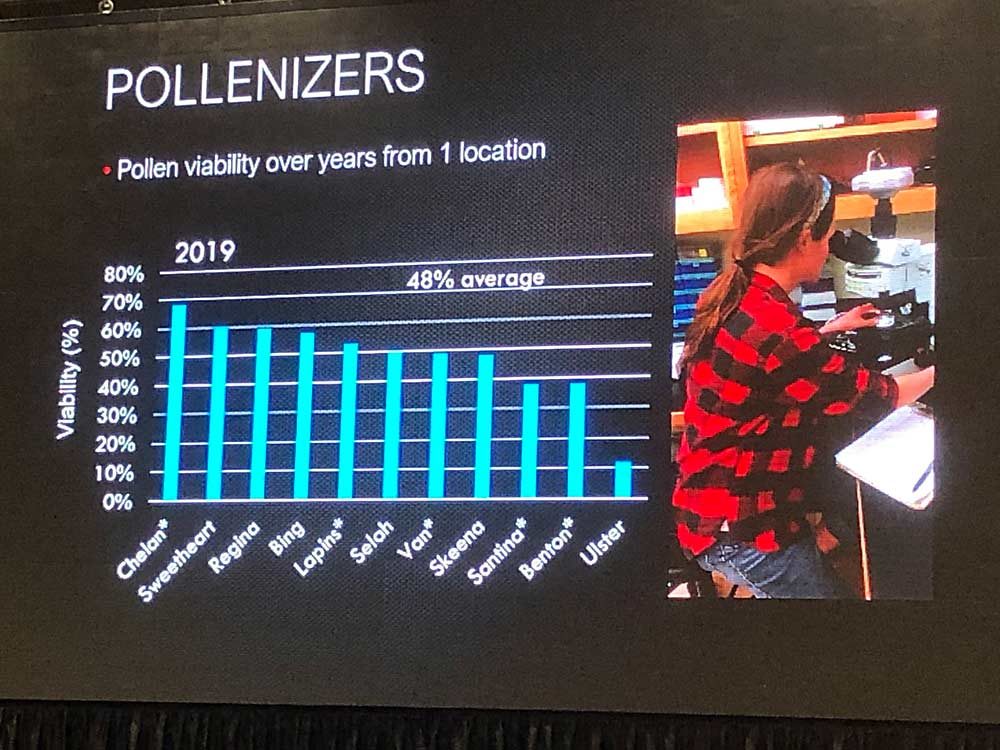

—Pollinizer research reveals patterns

Leave A Comment