Yesteryear, when nurseries introduced a new variety to growers, volumes grew from the ground up — from growers, to packing companies and then to sales teams.

Today, the trend is toward the reverse, as branded varieties have made the process more controlled and more global. Variety owners now look first at potential markets and distribution, then work to find shippers, packing facilities and growers.

“It’s become almost an industry in itself for the protection of varieties globally,” said Gavin Porter of the Australian Nurserymen’s Fruit Improvement Co. and CEO of the Associated International Group of Nurseries, or AIGN.

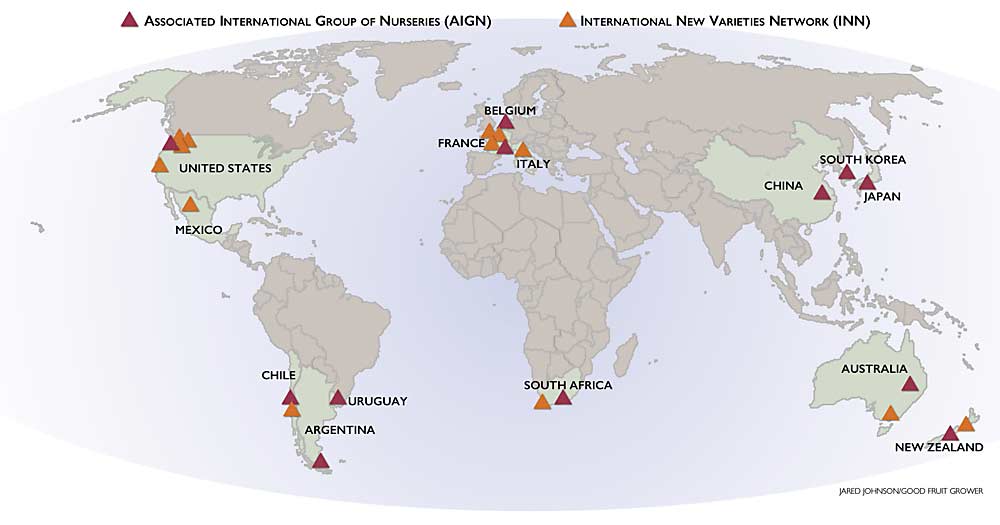

To both react to and drive the brave new world of branded fruit, AIGN and the International New Varieties Network (INN), the two most globally entrenched nursery networks, are reorganizing to take a more visible, aggressive role in variety management.

In May, some 20-plus members of AIGN gathered in Yakima, Washington, for an annual meeting to discuss everything from the quarantine process in different nations to changes in U.S. laws that extend plant variety protections to grafted plants, which fall more in line with the rest of the world. Good Fruit Grower had a chance to chat with the group’s leaders about priorities.

“The global village we live in is becoming smaller,” Porter said.

AIGN also has been revamping its website and centralizing variety performance information in a database named Hertha, which all members can access.

For its part, INN recently contracted a new general manager with a long history of branded variety management, is revamping its website and is actively pursuing new varieties instead of relying on members to bring them forward.

Behind all these changes is the world’s fruit market, shifting from open commodities that anyone can grow and sell to brands for which fruit standards, supply and sales are all controlled in an increasingly sophisticated world of intellectual property rights, international plant treaties, quarantines, global performance evaluations and politics.

“Now, it’s just about completely backwards,” said Jack Snyder of C&O Nursery, one of the members of INN.

History

The trend started with ENZA, the New Zealand marketing “monopoly” that released the Gala, Braeburn and Fuji, all public commodity apples, said Desmond O’Rourke, a tree fruit market analyst in Pullman, Washington. Soon, it became clear that open varieties, even good ones, would eventually oversupply the same way Red Delicious oversupplied.

That’s when the New Zealanders switched and the breeding program HortResearch worked with ENZA to commercialize the Pacific series, including Pacific Rose, to select production companies and limit supply — the model the industry now calls clubs. A successor private company, called ENZA Ltd., inherited the rights to the Pacific series, as well as to Jazz and Envy. HortResearch has since been absorbed into a larger New Zealand national organization called Plant & Food Research.

New Zealand remains a hotbed of innovation in apple and pear varieties, O’Rourke said. The commercialization work is now dominated by Prevar, which is partly owned by New Zealand Apples & Pears Inc., Apple and Pear Australia Ltd. and AIGN.

Nursery groups such as AIGN and INN have positioned themselves to be first in line for information. As new varieties roll out, developers look to nurseries to sell them. With global members, the two partnerships can steer those varieties through the quarantines and breeders’ rights deadlines around the world and learn how they perform in different regions before anyone plants them commercially.

However, only those two groups and the breeders have access to the intel; that information is proprietary. Independent growers looking to diversify plantings are left out.

“The big question, really, in all this is will these investments pay off?” O’Rourke said. Most likely, some will and some won’t. “Ultimately, consumers and retailers will determine winners and losers,” he said.

Competing with volume through brands

Branding is the only way for Western companies to compete with producers of commodity apples that grow and pack them for lower production costs in China, Poland and other Eastern European nations, said Florent Geerdens, vice president of AIGN and a nursery executive from Belgium. Of the varieties propagated by Geerdens’ Belgian nursery, 85 percent are proprietary brands.

Brands for which AIGN has played a role in global propagation rights include: Rockit, Smitten and Lemonade apples; Reddy Robin pears; and a few unnamed cherry varieties.

Geerdens expects Eastern Europe — Poland, Romania and Ukraine — will eventually follow the same business model of brands and intellectual property to generate more profit and higher grower returns.

The global market is proving that consumers will pay for brands if they believe it means consistent quality and production. For example, Pink Lady, a brand of the Cripps Pink variety, does more sales in Africa than continental Europe, said South Africa’s Rob Meihuizen, executive director of AIGN. “That just shows the value that the consumer, a very poor consumer, can see in a brand,” he said.

That’s because apples don’t feed the world, said Garry Langford, general manager of INN, from his office in Tasmania. Grains and proteins do that. Yes, apples are healthy, but people around the globe buy apples because they want them, not because they are starving.

There’s a lot of room for growth in this new world of brands, he said. Commodity apples still comprise most of the world’s production. INN represents 60 new branded apple varieties that make up only 3 percent of its volume.

For growers to keep up with these complex changes, Langford makes many of the same recommendations frequently preached at annual meetings and conferences. Stay abreast of changes in the industry. Attend trade shows. Ask what larger, neighboring companies are planting, and why. Seek alliances with packers and sales groups known for introducing new products.

“The new variety is not going to come down the road and knock on the door,” he said. •

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment