Wooded pines and cherries fit unexpectedly well in Coldstream, British Columbia, where on a south facing ridge several verities thrive in one of Coral Beach’s higher altitude, and late season, blocks grow. 2018 International Fruit Tree Association summer tour attendees listened to Coral Beach orchard manager, Gayle Krahn, on July 24, talk about how the company has taken risks going higher and later with BC cherries and the horticultural obstacles they’ve overcome. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

On a breezy hillside outside Coldstream, British Columbia, Canada, 65 acres of Staccato, Suite Note and other cherries grow where farmers once assumed they would not.

The slope was a cattle ranch until 2014, and the valley just upstream from the northern shores of Kalamalka Lake has a history of apples.

But cherries? Too cold, they said.

(Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower)

That was before the rush of late-season varieties that allowed Okanagan Valley orchardists to push cherries farther north and higher uphill than ever before, capitalizing on a market unfilled by their neighbors to the south in Washington state.

Already, cherries in the British Columbia interior come off trees in early September, while Coral Beach is trying to push harvest back to as late as mid-September.

“It’s worth the risk … to target that late season,” said Gayle Krahn, an orchard manager for Coral Beach’s Vernon-area properties, as she showed a fourth-leaf block to participants of the International Fruit Tree Association’s summer tour, this year held in British Columbia in late July.

Others must agree.

Sweet cherry acreage in British Columbia has jumped from 1,700 to 4,800 acres over the past 20 years, with a farm gate value skyrocketing from $5.5 million Canadian to $84.7 million.

Meanwhile, apple acreage has decreased, while farm gate value of apples remained relatively steady in the same period.

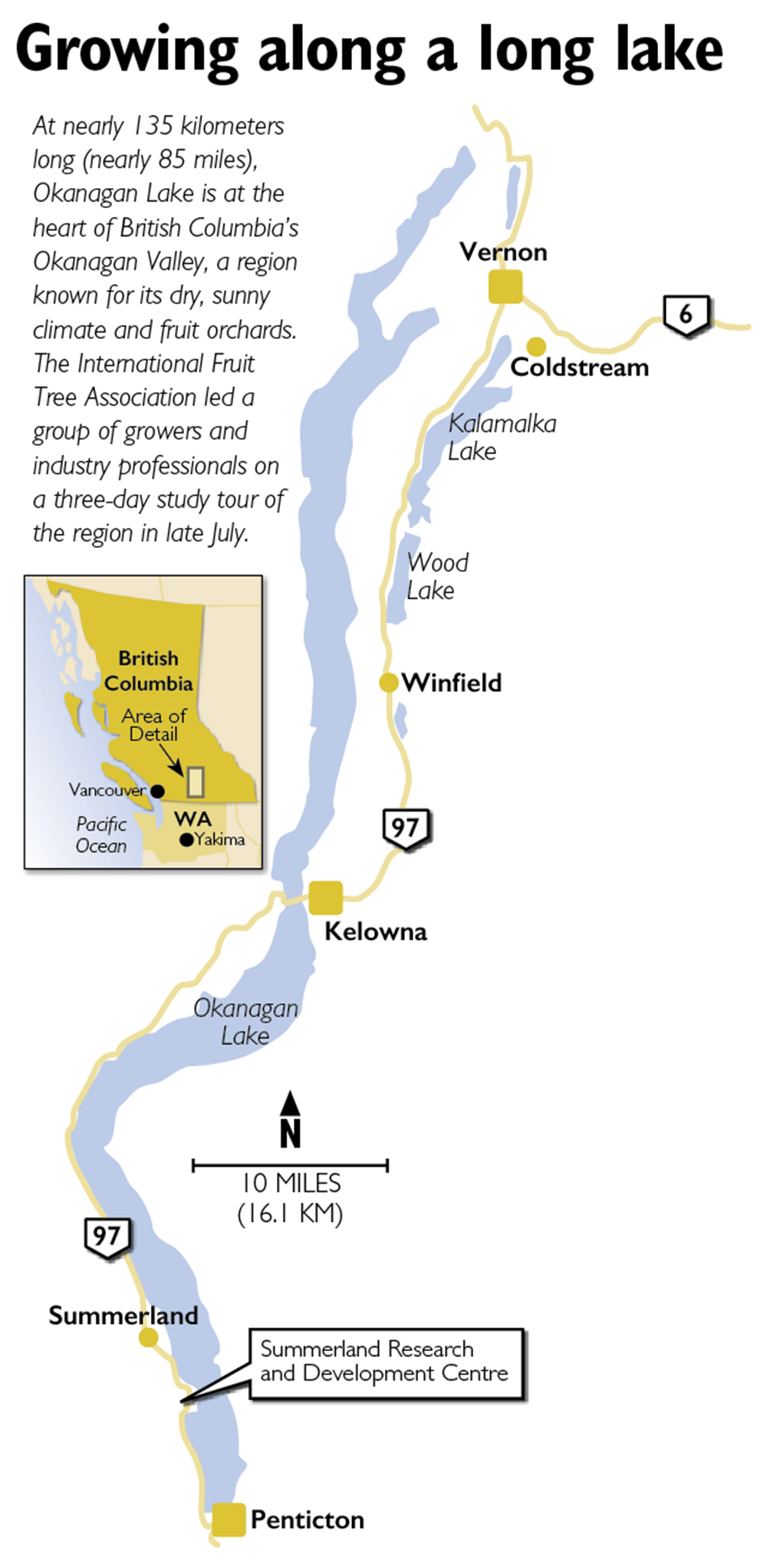

Coral Beach is one of the largest sweet cherry growers in Canada with 900 acres or so overall in the Okanagan Valley, a sliver of a growing region amid a string of lakes in southcentral British Columbia stretching from the arid climate at the Washington border roughly 150 miles north to more verdant Salmon Arm.

The area’s farmers can’t compete with the sheer volume of Washington, home to 40,000 bearing acres and 263,000 tons of cherries, but they can hit the market’s sweet spot timing wise.

“Our goal has always been to be the last guy on the market,” said Hank Markgraf, horticulturist for BC Tree Fruits, an apple, cherry, pear and stone fruit packing cooperative with 430 grower-members.

Summerland varieties

Enabling the cherry surge has been decades of work at Agri-Food Canada’s Summerland Research and Development Centre, where fruit breeders have developed the late-season varieties.

Lapins were the first big hit and today are the No. 1 variety by volume in British Columbia, but the work has expanded to Suite Note, Sandra Rose and Sentennial to name just a few.

Staccato has been the top planted variety for the past five years, said Nick Ibuki, business development manager for Summerland Varieties Corp., a private company that works with the center to commercialize the new cultivars. (The center names most new cherry varieties with words starting with S after Summerland.)

“We really need to distinguish ourselves with quality and timing,” Ibuki said.

The research station was one of the IFTA tour stops, where Ibuki described yet-unnamed varieties under development, some that may harvest in mid-September. It’s been a long process; some of the crosses were first made 20 years ago.

Suite Note hit the sweet spot with International Fruit Tree Association summer tour attendees on the July 23, 2018, stop at the Agri-Food Canada’s Summerland Research and Development Centre. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

The company plans to release most of the new varieties as a club program, with specially licensed growers around the globe, to protect the security of royalties to keep funding the program, he said.

Breeding is part of the answer for the northward push, but so is global warming, said Carl Withler, an industry specialist for the Canadian Ministry of Agriculture. “Whether you agree or disagree, there has been some change in climate in this part of the world,” Withler told part of the tour group on one of the buses.

The Summerland researchers have tracked climate data as it relates to cherries since 1961, when growers only produced cherries on small acreage plots at the very south end of the Okanagan Valley in Oliver and Osoyoos near the Washington border.

His own family near Osoyoos had only 1 acre that picked within a three-week July window every year. That has gradually shifted north over the years, while growers now focus on cherries, planting in blocks of 200-acre blocks.

“For us, in this part of the world, the cherry industry has been a real success story,” he said. “… It’s a nice contributor to the economy of this valley and it does it year after year after year.”

Coral Beach

Gayle Krahn, Coral Beach orchard manager, says the Coldstream ranch’s rich soil helped their trees, planted in 2015, take off. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

Besides Coldstream, Coral Beach Farms has new cherry plantings in other northern, late stretches of the Okanagan Valley. One is nearby Winfield. Yet another is the Eldorado orchard, 98 acres at 2,600 feet.

The company won’t start picking that one until early or even mid-September, said Craig Dalgliesh, another of the company’s orchard managers.

El Dorado is so high and late that snow makes getting equipment into the orchard before April a challenge and shutting the trees down in time for winter is tricky, he said.

“I don’t think we’re brave enough to go much higher just yet,” he told the IFTA group, but admitted the company likes to push the envelope.

The company is moving farther north, though.

This year, Coral Beach is scoping out a potential site for 250 new acres of cherries so far north near Pritchard — where it’s even a little warmer than the main farm near Winfield — that it falls into the Thompson River system, which drains westward toward Vancouver.

The Okanagan Valley waters flow south and ultimately feed the Columbia River, which empties into the Pacific between Oregon and Washington.

The farm, owned by fourth-generation growers David and Laura Geen, is doubling down on cherries, expecting to cross the 1,000-acre threshold by 2021 and currently building a new packing facility at the Winfield location.

The farm’s most common variety is Staccato, but its website lists 10 cherry varieties by name, harvested from mid-July through September, and has several trial plots of yet-to-be released Summerland varieties.

The company sells its products under the trade name Jealous Fruits.

Coral Beach is not the only one gambling on cherries.

Staccato nursery cherry trees growing at one of Joel Carter’s cherry blocks in Summerland, British Columbia, on July 26, 2018. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

By next year, Joel Carter will have added 8 acres of cherries to his 21 acres at his Summerland apple and cherry farm, simply because the money seems to be in cherries these days. Three years ago, 1 acre of Staccato cherries fetched him $60,000 — in U.S. money, he added.

“The returns on Staccato and Sentennial are so good, that even if you only get money every two years or something, it’s still great,” Carter said. •

—story by Ross Courtney / photos by TJ Mullinax

Watch: Training young cherry trees with strings at Coral Beach Farms (VR/360 Video)

The original version of this story printed in the September 2018 issue misspelled the name of Carl Withler, an industry specialist for the Canadian Ministry of Agriculture. Good Fruit Grower regrets the error.

Leave A Comment