It wouldn’t be an International Fruit Tree Association tour in Washington without V-trellis plantings of Honeycrisp.

But unlike 2017, the last time the association gathered in the Columbia Basin, when growers were optimistically investing in big new plantings, excited about using new rootstocks, new varieties and new systems, the 2022 tour found growers grappling with the challenges they discovered as those plantings came into production, such as vigor and labor costs. Pragmatism has replaced 2017’s optimism, with growers facing rising labor and input costs, stagnant prices, stalled exports and climate challenges.

Still, growers welcomed the tour to share what they are learning about systems, rootstocks and technology.

“Our industry is facing some headwinds right now,” said grower and nursery owner Dale Goldy. The planting boom five years ago has subsided, as growers face tight budgets and an uncertain outlook. That’s quite a change from 2017, when new varieties like WA 38 and hot rootstocks like Geneva 41 were in such demand that nurseries couldn’t keep up. (In July, the tour Cameron Nursery gave the IFTA included beds of G.41 and WA 38 being removed for lack of demand.)

Take Monument Hill Orchards, near the central Columbia Basin town of Quincy, as an example of those late twenty-teens plantings now in full production. The 125-acre orchard, a mix of Premier, Firestorm and Royal Red Honeycrisp, was planted on V-trellis in 2016, when Geneva rootstocks were in short supply. Now, the managers contend with managing a mix of roots in different blocks, said Tom Gausman of AgriMACS, the management company farming the orchard for International Farming, an institutional investor.

“The G.890s won the race to the top wire, but the M.9-337s are now outproducing them,” Gausman said. “I love 890s for replant sites but wouldn’t do that here again on this vigorous soil.”

Gausman and colleague Jeff Pheasant talked with the tour about the challenges of vigor and training and their approach to crop load management. The block was covered mostly by 20 percent shade netting, but it was hit with a “really devastating hailstorm” in early June, before all the nets were installed, Gausman said.

The uncovered blocks will be harvested only for processing.

That’s just one of many rare-for-the-region weather challenges that have struck recently, including unprecedented heat stress last summer and a cold, wet spring that combined to leave growers with low fruit set in many regions, for a variety of reasons.

“We just did not come back with a bloom after last year. It just got so hot during floral bud development. We can’t blame the bees,” said Scott McDougall, co-owner of McDougall and Sons, in a Quincy-area Honeycrisp block. “The only good news is we hope it (a short crop) will get the f.o.b. up.”

V-trellis orchards

McDougall hosted the tour at a sixth-leaf block of Premier Honeycrisp, planted on M.9-337 roots and trained in a V-trellis. The orchard was covered in an innovative retractable shade netting system to balance sun protection with color development, which was an expensive retrofit, according to area manager Dave Chism. (Read more on netting when our IFTA coverage continues in the October issue.)

The Quincy-area orchard is transitioning to organic, which revealed a new dilemma, McDougall said. Premier is a new variety for them, and last year they lost an estimated 20 bins an acre to preharvest drop. In conventional blocks, ReTain (aminoethoxyvinylglycine, or AVG) solves that problem, but without an organic version available on the market, they may have to abandon organic production for this variety if the problem continues, he said.

The company recently made a similar switch in a struggling block of WA 38, the apple marketed as Cosmic Crisp, and after conventional fertigation, the block looks great, McDougall said. There’s not enough of an organic premium anymore to accept lower production, he added.

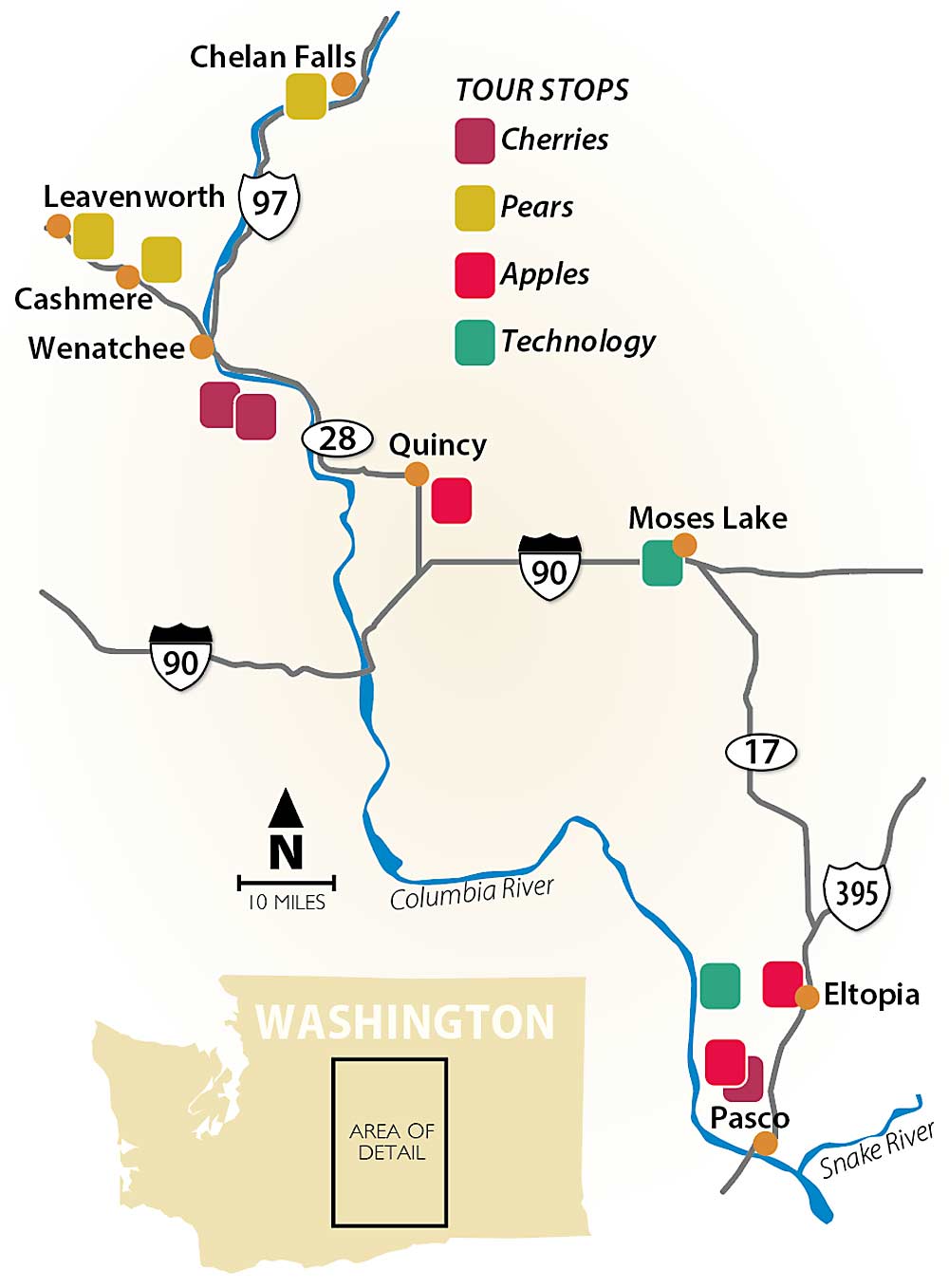

The tour also visited a WA 38 block owned by Douglas Fruit, located just north of Pasco in the southern Columbia Basin, where manager Garrett Henry shared some of the early challenges the company had with its first plantings in 2018.

“We like classically trained trees here,” he said of the trees, which were planted as sleeping eyes on G.11, Bud.9 and Bud.10 at 2.5 feet by 13 feet and trained to a V-trellis. “Due to labor constraints, we didn’t get them trained right away.”

The trees still haven’t reached the top wire — but Henry credits that to the tree training, not rootstock selection. “I think if we execute correctly, we can fill the space in three to four years,” he said, adding that starting with a nice nursery tree helps. His 2020 plantings, on G.11 and G.41, which the tour didn’t visit, have filled their space better, he said. After planting, they headed all the branches back to 3 or 4 inches and decided against cropping until the trees grew enough.

“Sometimes, we have to sacrifice some apples to thinning now to get these trees to fill space,” Henry said. “It’s the now versus the future.”

Vigor management

Managing vigor was a theme at several of the orchard stops, especially in Quincy, where new orchards have replaced potatoes in wide, flat farms with deep topsoil.

There, grower Kent Karstetter showed the tour a 10-year-old block of Honeycrisp, planted on M.9-337 at 2.5 feet by 10 feet, trained in a spindle. In recent years, the block has produced about 100 bins an acre, he said, which may have been too much.

“We were trying to suck the energy out of the tree,” he said. “But we had to leave some fruit because they didn’t finish. I don’t recommend that.”

When he was pruning the trees into a very narrow canopy that produced apples close to the trunk, he found that the fruit ended up enormous and prone to bitter pit. Now, he’s leaving longer branches bearing more apples, which reduces the fruit size. It takes a lot of labor to get the pruning and thinning right, but Karstetter said that when he started to consider those costs on a per-bin basis, rather than per acre, the value became clear.

The Karstetters have also turned to automated irrigation to apply just enough water stress to keep the vigor under control, Kent’s son, Mitchell, said.

At nearby G2 Orchards, grower Dale Goldy introduced his approach to vigor management: a pedestrian Minneiska orchard planted with 7-foot-tall nursery trees (custom produced on G.935 at Goldy’s Gold Crown Nursery) already touching the top wire. The block was inspired by the observation that Minneiska, the apple marketed as SweeTango, produced the best quality fruit in the narrow tops of older plantings. “So, we came up with this system to imitate those tops,” Goldy said.

But to get enough production off just the “tops of the trees” meant squeezing a lot more trees in — which he did by using 6-foot rows. Because he planted the trees at full height, he didn’t need to fertilize to push growth, Goldy said, which can have consequences for fruit quality in the first years of production. Now in its fourth leaf, he expects 75 to 80 bins an acre this year, but the block was producing enough to break even in its second leaf.

Eventually, he hopes to manage the trees with hedging, but he hasn’t quite figured that out yet, Goldy said. He did show the tour group a custom-built bin train that workers ride on as they pick and a custom over-the-row sprayer. Both were built by Automated Ag of Moses Lake, which hosted the tour for a dinner of pizzas baked in the enormous oven that cures the signature orange powder coat on its equipment.

Technology

At many stops, the IFTA hosts asked growers about technology making a difference for their farms. While some growers mentioned platforms, most of the technology talk was focused on sensors for precision agriculture, rather than mechanization.

It’s a trend exemplified by the Smart Orchard project, a collaboration between Washington State University, the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission, tech company innov8.ag, and two commercial orchards to create a proving ground for the value of deploying different sensor technologies in apple orchards.

“We want companies to come in here and try,” said Steve Mantle, founder of innov8.ag and coordinator of the Smart Orchard project hosted at a Chiawana Orchards’ Gala block north of Pasco. That includes everything for soil mapping, irrigation sensing, weather stations and drone imagery.

One technology showing promise is an ATV-mounted crop load imaging system known as the Cartographer, developed by Australian tech company Green Atlas.

Chiawana area manager Chris Hammond said the data from the Cartographer helps them be more efficient with their hand thinning for size-sensitive varieties such as Gala and Honeycrisp. The maps of crop load variability help them “send thinning crews to the most needed areas,” and skip others when demand for labor is at a premium, he said.

Precision irrigation technology was another theme. At the Smart Orchard, WSU physiologist Lee Kalcsits talked about how plant-based sensors can track tree stress and fruit growth to control vigor and optimize fruit size.

For example, at Monument Hill, they use dendrometers to track tree and fruit growth to assess water stress and provide just enough deficit irrigation in Honeycrisp to control fruit size, Gausman said.

Gausman was one of several growers who mentioned that their more recent plantings are moving away from the intensively trained V systems, toward simpler vertical systems that should be ready for future mechanization.

“We’re leaning more into vertical — 2.5 by 10 or 2.5 by 11 is now our preferred,” he said. “Vertical just seems simpler and we think, fingers crossed, robotic systems will be able to do that.” •

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment