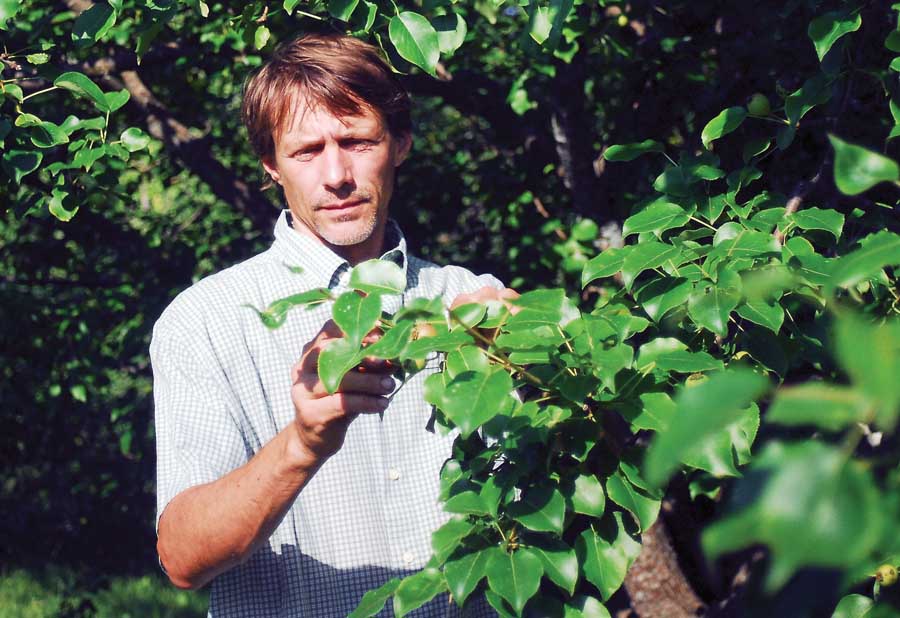

Todd Parlo, a Walden, Vermont, organic grower is evaluating 84 pear varieties as cold-hardy rootstock candidates. These David pears are one of the varieties he’s earmarked as a good possibility. (Courtesy Lori Parlo)

Todd Parlo has been growing organic fruit and operating a nursery at his Vermont farm for the past 20 years.

At 1,750-plus feet above sea level, his farm lies in a region where the average annual extreme low temperature reaches between minus 30 and minus 35 degrees Fahrenheit.

However, the majority of fruit tree rootstocks — pears included — are only cold-hardy above zero, which falls short of requirements for growers like Parlo.

“The Achilles’ heel of growing pears in northern climates is parent rootstock,” Parlo said. “Most people tend to put scions on European rootstock, but there is a limit to their cold-hardiness.”

Four years ago, he applied for and received a $14,000 U.S. Department of Agriculture Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education grant to evaluate the cold-

hardiness of 600 apple varieties and almost 85 pear varieties within organic systems. “We had an opportunity, with the SARE grant, to get a large pot of cultivars and to do a little more rigorous recordkeeping,” Parlo said.

He did his own grafting, but nearly all his test varieties came from commercial nurseries, many of which are located in the northern United States and Canada. “What I couldn’t find commercially, I was able to get from the national germplasm collections,” he said.

His research is ongoing, but so far Parlo has identified eight possible pear candidates that could serve as rootstock in colder regions.

Cold’s advantages

There are some positives associated with growing in colder regions, including an absence of fire blight, virtually no plant diseases and fewer pests. In Parlo’s region, growers deal with only two pests: blister mites and tarnished plant bugs.

Another advantage is the region’s snow cover, which acts like an insulating blanket during frigid weather.

In Parlo’s case, temperatures periodically fall to 40 degrees below zero, but Parlo doesn’t fear a severe low temperature as much as a rapid change in temperature that shocks the tree, leaving it no time to gradually adjust.

In either case, roots are the critical concern because they are the least hardy part of the tree. “While trees can be cold-hardy up top, the roots are not because they are insulated by the soil throughout the year,” he said.

The cold-hardiness of most temperate fruit roots is actually above zero. There are rootstock selections compatible with cold-hardy European varieties and available for growers located in regions with negative temperatures, but not extreme cold like Parlo’s region.

Seedling rootstock tends to come from Bartlett seeds, which Parlo said, “are not terribly cold-hardy.”

Clonal rootstock isn’t an answer, either, because its plant hardiness seems to be closer to minus 30 degrees than minus 40 degrees.

Parlo’s best rootstock options are Old Home by Farmingdale 97, 513 and 333. “OHxF.97 is the most vigorous one and it’s pretty hardy, but not that hardy,” he said.

OHxF.513 and 333 are slow growing, which is a separate problem. “A late ripening pear can still have leaves when we begin to see freezing weather,” he said. “If it freezes and it’s succulent, it’s done.”

He also uses Pyrus communis, the European pear or common pear, but generally uses his own seed. “It comes from hardier genetics than commercially available, cannery-generated strains,” he said.

P. ussuriensis is the most cold-hardy stock, but when European scions are put on top of them, pear decline becomes an issue. “Asian varieties are not very cold-hardy at all,” said Parlo.

Some growers use quince as rootstock, but it isn’t hardy enough for Parlo’s region.

Early picks

Most of Parlo’s varieties are bitter tasting and not suitable for use as a scion.

(Left) developed in 1933 by the South Dakota Experiment Station, the female parent of Krylov pears hails from eastern Siberia. The variety is fire blight resistant. (Center) The Stacey pear mother tree is believed to be nearly 300 years old and measured 108 inches in circumference in 2006. It produces a small, sweet fruit that should be picked in mid-August before it ripens and placed in cool storage. (Right) Summercrisp pears have good resistance to fire blight, ripen early and store for six weeks in refrigeration. Flesh is crisp, juicy and has a mild flavor, but browns internally when allowed to ripen before storage. (Courtesy of U.S. Department of Agriculture/Agricultural Research Service

and UMN Ag Experiment Station)

Parlo is quick to point out his trials are ongoing; still, he’s identified eight probable candidates for rootstock:

—Stacey is an early bearer with an acceptable form. Blister mite was less a problem with this variety than others in his test.

—Summercrisp displays good form and is vigorous without being excessive. It’s susceptible to blister mite

—Luscious has moderate vigor and good cold tolerance. It seems to have a pollen issue, requiring it to be grouped with other pears. Its foliage tends to be less lush than others.

—Hardy has a very vigorous tree that grows straight up like a poplar. It suffers from some cold damage. It has dieback issues on the new shoots, but they do grow back. “We’ve had no fire blight strikes on this one,” he said.

—A David pear tree shows good form, has spreading and well-angled branches. It also shows some resistance to blister mite.

—Krylov produces a vigorous and healthy tree with fair form. It shows no cold damage. No pear decline has been evident and it shows signs of blister mite resistance.

—Two of his own local varieties also show promise: Hill and Walden Large. They both exhibit excessive vigor with upright growth and form, making them hard to manage. They are moderately susceptible to blister mites.

Having reviewed Parlo’s list of varieties, Joseph Postman, curator of USDA’s National Clonal Germplasm Repository Collection in Corvallis, Oregon, agreed about the varieties’ astringency.

“But a number of these could make some good rootstocks,” he said. •

– by Dave Weinstock

[…] L’article de Good fruit growers: https://goodfruit.com/in-the-hunt-for-cold-hardy-pears/ […]

[…] Hunt for Cold Hardy Pears – Good Fruit Grower Magazine […]