It’s not your imagination — costs of production are rising even faster this year.

That’s why Washington State University economist Karina Gallardo took on a last-minute update to her sweet cherry cost-of-production budgets — which were set to be published with 2021 data — to reflect a few key 2022 cost increases.

Specifically, she upped the wage rate, the price of fuel and other petroleum products and the price of urea. For a 12-acre Sweetheart block in full production, fuel and lube cost $360 per acre this year, she found, compared to $180 in 2021. In 2022, she puts fertilizer inputs at $241 per acre, compared to $227 last season.

In Washington, the Adverse Effect Wage Rate is now $17.41 (up from $16.34 last year), but Gallardo calculates labor costs have risen an additional 25 percent to reflect the cost of H-2A administration and housing as well, bringing the rate used in her calculations to $21.76 for hand labor and $23.01 for tractor drivers and irrigators. (That’s up from $20.43 and $21.68, respectively, in 2021).

Gallardo works closely with growers, crop consultants and WSU Extension to gather the data and develop her approach to the budgets, which she completed for Chelan, Coral Champagne, Skeena and Sweetheart varieties to represent different harvest timings and market windows.

“The quality of this study depends on the quality of the data growers are able to provide,” she said.

The full reports are available online, including spreadsheets detailing the assumptions of her model orchard: a 12-acre cherry block that is part of a 300-acre farm planted to apples, cherries and pears. She breaks out establishment costs and full production costs, as well as interest costs, equipment depreciation and the opportunity cost of not investing money elsewhere. Growers can download and modify the spreadsheets with their own numbers in some places. Figures in orange text can be changed by the user; those changes then ripple through the calculations to the conclusions. (To find the budgets, head to: ses.wsu.edu/enterprise_budgets and search for “cherries.”)

In 2021, Gallardo set out to update the cost-of-production calculations she previously completed in 2016 with 2015 data, incorporating new costs such as testing for X disease and spraying for the leafhoppers that can spread it after harvest, as well as rising labor costs, chemical costs and land values.

The attention to detail on how cherry farms operate — for example, a late-harvesting Sweetheart block has higher need for preharvest chemical application than an early ripening Chelan — is what makes the study so valuable, said Denny Hayden, a Pasco-area grower.

The report is “driven by real grower information,” said Hayden, who reviewed the 2021 findings and pushed for the 2022 update. “It was pretty impressive, the amount of work that went into it.”

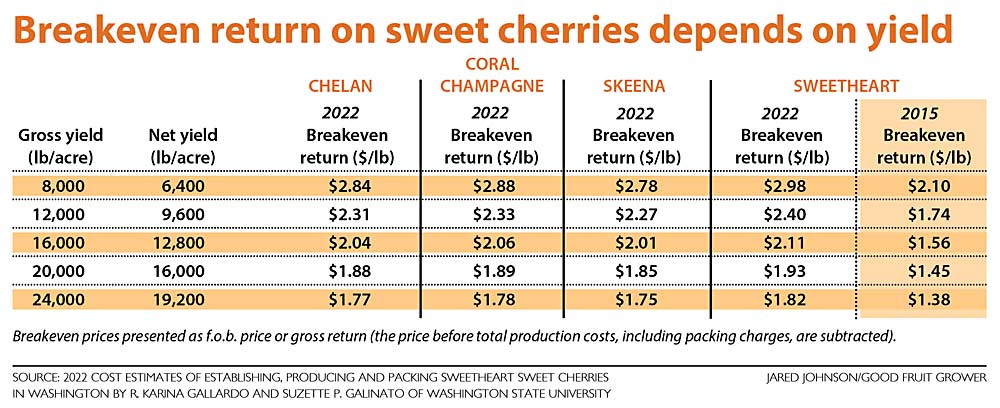

Hayden particularly praised the table of “breakeven prices” that shows the relationship between an orchard’s yield and price needed to keep the block in the black.

For Sweethearts picked at 12,000 pounds per acre (translating to 9,600 pounds of packable fruit), those cherries need to sell for $2.40 per pound for the grower to break even. A lighter crop of just 8,000 pounds per acre pencils out at $2.98.

In 2015, the breakeven prices were $1.74 and $2.10 in those same scenarios (with the caveat that Gallardo and her colleagues adjusted their approach from 2016 to 2022, so it’s a close but not perfect comparison.)

It’s also important to note that the prices the report presents are f.o.b. prices, not grower returns, Gallardo said. Her analysis includes the fact that packing charges (estimated at 0.60 cents per pound) would be subtracted.

That’s because the audience for these findings should be customers, who need to know how much costs of production have increased, Hayden said.

“I don’t think we’ve been good at keeping this information in front of the retail trade,” he said.

But how much influence can a report such as this have on prices?

“The market is going to be the market. It’s a living, breathing thing,” said B.J. Thurlby, the president of Northwest Cherries. Volume — not production costs — is the primary influence on prices.

A few years ago, the Northwest Cherries board of directors declined to fund a study like this, citing concerns that if a breakeven price estimate existed, it could be interpreted as a ceiling, rather than a floor, in price negotiations. Moreover, the actual breakeven price varies from grower to grower and orchard to orchard.

WSU’s work is supported by a large U.S. Department of Agriculture grant focused on integrated pest management of spotted wing drosophila, Gallardo said. A priority of that project is to understand the costs of cherry production, including control of new pests such as SWD and disease-vectoring leafhoppers.

But the data has value far beyond that.

Mike Preacher, marketing director for Domex Superfresh Growers, said the work by Gallardo and her colleagues is very valuable for the industry and will help with marketing the crop correctly.

“It’s crucial for us as cherry producers to understand what our cost of cherry production is, because if we aren’t profitable back to the land, the surety of supply diminishes,” he said. That’s a concern for growers and retailers alike, as cherries are a “crucial, sales-driving product.”

The report itself is unlikely to be part of conversations with customers. “It’s a tool to ourselves as industry marketers, so we start that negotiation from a good spot,” Preacher said. “That is particularly important in a season like this one in which cherries appear to be short of potential supply.” •

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment