—story and photos by Kate Prengaman

—photo by TJ Mullinax

Pears make up over 70 percent of orchard production in the Netherlands, so you would expect a visiting delegation of Dutch growers, ag consultants and ag tech developers to feel at home in the Wenatchee River Valley, where pears are the top crop.

But during their July trip, the visitors laughed off this suggestion. Pears in the Netherlands are a high-density affair. In contrast, most of the Wenatchee River Valley’s orchards are 40 to 50 years old and, up until recently, remained so productive that growers saw little incentive to change, said grower Shawn Cox, who hosted the group.

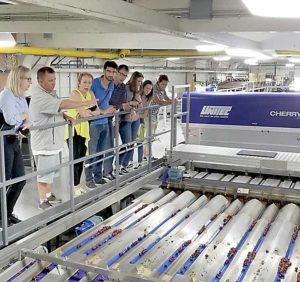

Training systems aside, the Dutch visitors found plenty of common ground with the Washington growers as they talked about rising labor costs and technology implementation. That was the goal of the weeklong tour, said Ines Hanrahan, director of the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission, which organized the July tour of Washington and a May trip to the Netherlands as part of the two industries’ Orchard of the Future collaboration.

“To move technologies forward, we need to have this relationship so growers can peek at each other and see what they are implementing and why,” she said.

The roots of the collaboration date back to 2020 and involve co-funding the development of orchard innovations by university scientists and tech companies in both regions, with grant support from the Dutch government, the Washington State Department of Agriculture, the research commission, and the pear research subcommittee. Going from research to implementation of new technologies now requires getting more growers involved, Hanrahan said.

While the farming system in the Netherlands is quite different, with smaller, family-run farms being the norm, the challenges driving technology adoption are very similar, said Jon Cox, vice president of research and development for Double Diamond Fruit. Cox was part of the group that visited the Netherlands in May.

One challenge facing agricultural innovation in both regions is the lack of incentive for growers to be the first to test a new technology. The first customer pays for the privilege of having to navigate all the bumps in the rollout road, while the tech company learns from that experience to improve future versions of the product to sell to other customers, said Niels Feder, a fruit growing advisor for research and consulting firm Delphy.

But without those first customers willing to be proving grounds, needed technologies won’t advance to where they need to be. In the Netherlands, the government supports the work needed to move new technology across that commercialization gap, and it supports growers who participate, said Matt Miles of Allan Bros., who also visited the Netherlands this spring.

“The Dutch government has, for years, taken a vested interest in helping to cultivate agricultural technologies,” he said. “The farmer mentality here is: ‘We can figure it out ourselves,’ but having that government help can kickstart things.”

Hanrahan said that’s one lesson the commission is taking from the collaboration, and she is looking at how programs such as tax credits for trying new farm tech could create support for early adopters in the U.S.

The tours also connected Northwest growers with new technologies. Miles said he was particularly intrigued with Agromanager, a Belgium-based company that developed a central data platform for orchardists.

“So, all the data will be in a single system,” he said. “In the tree fruit field, they are leveraging data and automation better than we are, hands down.”

The Agromanager platform acts as a hub, connecting one company’s sensor data to make task maps for another company’s smart sprayer or root pruner, said grower Andrew Sundquist, another tour participant. And it connects those emerging technologies with all the record-keeping growers need for audits, putting everything in one place.

“Every stop we went to, they were talking about Agromanager,” he said. “We have all the bolt-on stuff, too, but don’t have that center of the hub.”

Berdien Rosmuelen, a customer success manager at Agromanager, said the company was preparing to expand into the U.S. That involves both technical updates, such as swapping hectares for acres, and getting to know a new industry, she said. •

A robotic wrist

From a robot’s perspective, picking a pear proves much harder than picking an apple.

But a team of scientists at Wageningen University and Research in the Netherlands demonstrated that it can be done using a suction cup end effector on a robotic arm with a “wrist” that swings the pear up to gently detach the stem. Performing that motion at the end effector, rather than with the arm itself, makes the action more efficient and reduces the interference with branches, said Peter Frans de Jong, lead researcher on the project.

It’s also harder to train algorithms to identify pears compared to apples: Pears aren’t round or red. At least, the Conference pears used to develop the technology aren’t. The researchers developed a program that understands the shape of pears and the target location for the suction cup to attach for picking, de Jong said.

The system can even identify the pears on USA Pears’ pear-themed Hawaiian-style shirts, he said with a laugh while wearing one.

The tests were performed on Conference planted in a spindle system with a 1-meter canopy depth, he said. Adapting the algorithms to different varieties or cultivars should be easy enough.

The next steps for the research: increase the picking speed and see if the pear end effector can be incorporated into an apple picking prototype that could put the fruit into bins.

“We showed the potential, and the next step is to find the companies to make it commercial,” de Jong said. “We showed the direction to go forward.”

—K. Prengaman

Pear-spectives

Yes, it was a technology-focused tour, but Good Fruit Grower wasn’t going to visit a high-density pear block with a bunch of high-density pear experts without asking for some horticultural perspective.

In a second-leaf block of the new variety HW 624 (marketed as Happi Pear), planted by Blaine Smith at 12-foot by 2-foot spacing and trained with three leaders in a V-trellis, we asked two Dutch crop advisors, Gijsbert Hakkert and Dirk van Hees, for their thoughts.

Both agreed that they like the look of the variety and the multileader approach to control vigor but said they would have liked to crop it more in the second leaf to keep the trees calm. While some apple varieties are known to stall their growth when cropped early, pears don’t have that problem, even on the dwarfing quince rootstocks common in the Netherlands, Hakkert said.

Van Hees said he was surprised to see that Smith’s crew had done some summer pruning. “We would never prune a pear when there are leaves on,” he said.

Instead, they would opt for root pruning, a common approach in the Netherlands, to reduce vigor and slow the upright growth.

But van Hees liked the click-pruning approach Smith used to keep the trees in their space and create the small branches that had set a lot of fruit buds for next season. He also recommends the click-pruning approach for the Netherlands standard of four leaders per meter, two trained to each side of a V-trellis.

“We keep the trees shorter,” Hakkert said, adding that there would be one less wire in a Dutch system, to ensure enough light can reach the lower canopy. “The pears at the top are more expensive to pick,” so it makes sense to sacrifice growth there for the lower production.

In Washington’s higher-light environment, he suspects that’s less of an issue.

—K. Prengaman

Leave A Comment