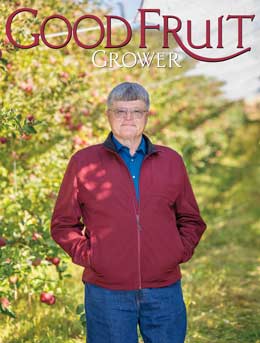

To Mike Robinson, everything in an orchard is connected.

An orchard is a fully formed ecosystem with mutually dependent parts. Adjustments to one mean adjustments to another.

“It all has to go together on horticulture, or you’re not going to win,” said Robinson, the 2021 Good Fruit Grower of the Year.

Robinson has given a lot of tours and presentations. It became one of his main jobs at Auvil Fruit Co., where he spent nearly 10 years working in most facets of fruit production. In recent years, too, he has hosted field days and in-orchard lessons for the International Fruit Tree Association and Washington State University.

Too often, Robinson said, attendees want to take home just a fragment of the lesson, something applicable they can change right away and boost profits. Though he understands the impulse, to his mind, those folks often missed the overall point.

Horticulture requires big-picture thinking.

Take his Aztec Fuji orchard near Othello, Washington, one of the first commercial blocks of the high-color strain in the country. In 2005, he flew to New Zealand for one day to inspect the apple, liked what he saw and flew straight home. He and his partners in BMR Orchards planted it on M.9-337 rootstocks at 5- by 12-foot spacing. So, he started with the right genetics, he said.

Then there’s his netting. He uses a louvered design that allows sunlight in the morning and provides shade in the afternoon. “It makes a big difference,” he said.

Left to their own devices, Fujis easily fall into alternate bearing. Cutting back on nitrogen to increase color makes that worse. The Aztec strain, and the extra sunshine from the louvered nets, afford enough color that the grower can fertilize enough for adequate annual bloom and avoid alternate bearing. Also, the M.9 rootstock boosts return bloom more easily than other choices.

Robinson does not cultivate the 4-foot strip of soil directly under the tree row, instead letting organic debris accumulate from mow and blow and 1–2 tons of compost per acre, much as it would in the forests of Central Asia where apples first evolved, he said. He doesn’t even plan to fertilize the block next year.

As part of his hands-off soil program, he uses a Dyna Trim, a disc-shaped machine that mows weeds under the canopy directly up to the tree trunks. The mowing cuts down on habitat for damaging insects and rodents, without cultivating the soil.

Back to that netting, which is also connected to the soil. Yes, it protects his fruit from sunburn and hail, but it also helps him manage water.

Robinson pointed out charts on a tablet that showed intentionally low soil moisture levels for his Honeycrisp blocks, which need more cooling but less water.

Robinson uses water only to irrigate, not to cool. His trees stay dry, cutting down on his need to spray for mildew. Nutrients don’t get flushed away, helping him avoid bitter pit, while fruit doesn’t develop excess size, he said. He sprays some foliar calcium in the summer.

The result: 18–20 packs per bin from his Honeycrisp blocks.

It all requires attention to detail. During the hot 2021 summer, he or an orchard manager physically checked the Honeycrisp blocks nearly every day. If he saw any sign of flagging, leaves draping in a downward wilt, he irrigated for a few hours.

“If you miss on any one of these things, you could have a problem,” he said. “Each one of them fits together.”

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment