Once an invasive fruit pest arrives in vineyards and orchards, history suggests that most often it’s here to stay. Every once in a while, however, scientists mount a successful eradication effort. Two recent victories are the European grapevine moth, which was first documented in California’s Napa and Sonoma regions in 2009 and eradicated there by 2016, and the oriental fruit fly, which was identified within the agricultural region of Florida’s Miami-Dade County in 2015 and eradicated in just six months.

Since these two efforts worked when so many others have not, invasive-species experts have begun teasing apart what went right to see if the lessons learned can be applied to the next invasive species that arrives on the farm.

Catch it early

For both successes with the European grapevine moth and oriental fruit fly, a key component was early detection of the infestation.

In Florida, local, state and federal entomologists were well aware of the potential threat from oriental fruit fly long before 2015, and they had a response strategy ready if the insect did show up, according to Gary Steck, an entomologist with the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services and lead author of a report on the eradication program. As a result, when oriental fruit flies showed up, they were able to mobilize quickly.

“This addresses the whole issue of why some things can be eradicated and some things not,” Steck said. “In the case of these fruit flies, we have two things going for us. One is an excellent lure called methyl eugenol that is incredibly attractive to the males (even) from a kilometer away, so it is as good as it gets. Second, we have an extensive trapping network.”

The statewide network includes some 55,000 traps for oriental and other fruit flies, and personnel who check them every two to three weeks.

With the European grapevine moth in California, entomologists also had the pest on their watch list before it appeared, but this time, grower reports of damage in grape clusters led to the initial discovery of the pest, said entomologist and cooperative extension specialist Matt Daugherty of the University of California, Riverside.

“We were fortunate in that a lot of European researchers, especially in Italy, had been working on this pest, so there was a pheromone identified and good protocols in place in terms of how to monitor for it,” Daugherty said. “So that helped kick-start the monitoring pretty quickly in California, and certainly faster than you would expect if you were starting from scratch.”

Keep it contained

For both European grapevine moth and oriental fruit fly, monitoring showed the pests had not yet become overly widespread, which made them good candidates for eradication efforts.

The grapevine moth’s low dispersal rate helped: Natural dispersal beyond approximately 200 meters (650 feet) is rare. Although scientists now suspect the moth may have arrived a year or more before it was identified, its inability to move long distances kept it fairly contained.

Oriental fruit fly, on the other hand, is a strong flier and individuals can travel over several kilometers, but because of its swift detection — perhaps as few as two generations before it was identified — it was still relegated to a few small areas.

Initial steps in both eradication programs included stripping fruit from infested and surrounding areas, as well as setting up quarantine zones. Treatment then switched to a combination of targeted insecticides and mating disruption, with the latter being especially effective once the pest population decreased, “because it’s just that much harder for the males and females to find each other,” Daugherty said.

Continued monitoring with pheromone-baited traps ensured the treatment was working and, later, showed that both invasive pests were and have remained eradicated.

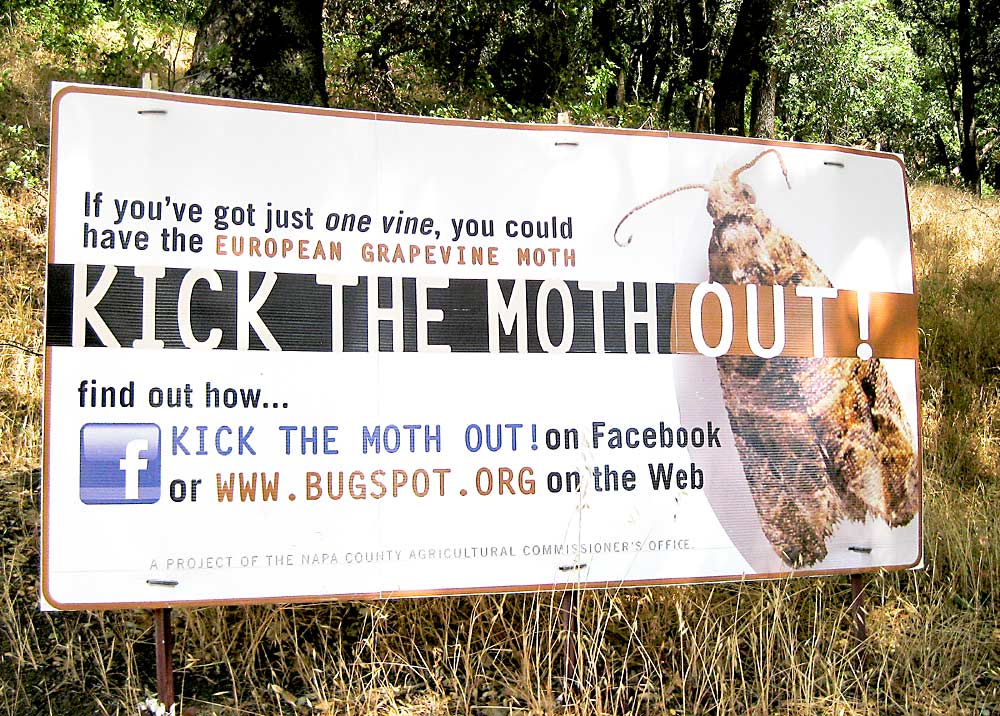

Throughout both programs, communication with growers, community leaders and the public has been key. That job was fairly easy in Napa and Sonoma, where the community is heavily invested in the grape industry and recognizes its importance to the local economy, Daugherty said.

Getting everyone on board was more of a challenge in Florida, which is home to thousands of small farm operators whose livelihoods depend on selling their fruit door-to-door or at fruit markets.

“They don’t want you even on their property to survey, because they know that if we find infested fruit, we’re going to strip it, which may mean the loss of many thousands of dollars for them,” Steck said.

Homeowners also often balk at treating their backyard fruit trees, sometimes even filing lawsuits to block pesticide usage. “That’s why public relations is hugely important, including getting in touch with local officials to be really transparent, giving notice about spraying, providing informative websites and holding public meetings,” he said.

Can it work again?

The European grapevine moth and oriental fruit fly eradication programs succeeded because everything came together: awareness of the potential for invasion, extensive monitoring with good lures, eradication-susceptible infestations and insects, effective treatments and communication to help ensure across-the-board cooperation.

Unfortunately, those criteria do not fit every pest insect introduction. With spotted wing drosophila, SWD, for instance, agricultural experts didn’t recognize it as a problem species when it first showed up in the continental U.S. in 2008, Steck said.

“We all knew about true fruit flies (in the family Tephritidae) — things like oriental fruit fly and Mediterranean fruit fly — but these other drosophila ‘fruit flies’ (family Drosophilidae) simply were not known as pests, and consequently, no one was out there looking for them,” he said. “They just weren’t on anybody’s radar.”

On top of that, SWD is a very fast multiplier, so by the time growers began noticing maggots in their fruit, it was already so widespread that management was the only real option.

SWD and other successful invasive species such as brown marmorated stink bug, BMSB, have the advantage of a wide host range, said entomologist and tree fruit IPM outreach specialist Julianna Wilson of Michigan State University.

“They’re very mobile, so they’re moving between different habitats, including wild hosts in the woodlots that are ubiquitous and dispersed within our agricultural landscape in Michigan,” she said. Large pest populations can survive outside pesticide-treatment zones and continually reinvade crops. That habitat advantage, combined with the current lack of highly specific lures, mating disruption options and natural enemies, has made SWD and BMSB formidable adversaries.

Nonetheless, the recent eradication successes give hope that it can be repeated. One way to make that more likely is to deconstruct successful efforts to figure out what went right. With European grapevine moth, Daugherty and his research team analyzed the effectiveness of the pheromone, evaluated the spread of the insect to see whether it was moving of its own accord or if it was hitchhiking on farm equipment or fruit bins, and investigated trapping density and treatment zones to ascertain the optimal number of pheromone-baited traps per unit area.

“Overall, we evaluated whether the procedures put in place were appropriate,” he said. “And by and large, they were.”

With USDA funding, Daugherty’s lab is continuing this line of study and conducting additional analyses to determine the risks from other moth pests that could potentially arrive in California.

“This is all proactive, prospective work to make sure we’re being smart, we’re learning lessons from the success last time, and if this EGVM gets reintroduced or a related moth gets introduced, we are ready to deal with it,” he said. •

—by Leslie Mertz

Leave A Comment