Many in the tree fruit industry have moved on from the 2014 Listeria monocytogenes illness outbreak associated with caramel apples.

They haven’t forgotten it, certainly, but they’ve turned their focus to other issues.

Even so, the outbreak was the lead session of the Center for Produce Safety’s annual conference this summer in Seattle, as researchers shared lessons learned and information gleaned from the case with food safety professionals from across the world.

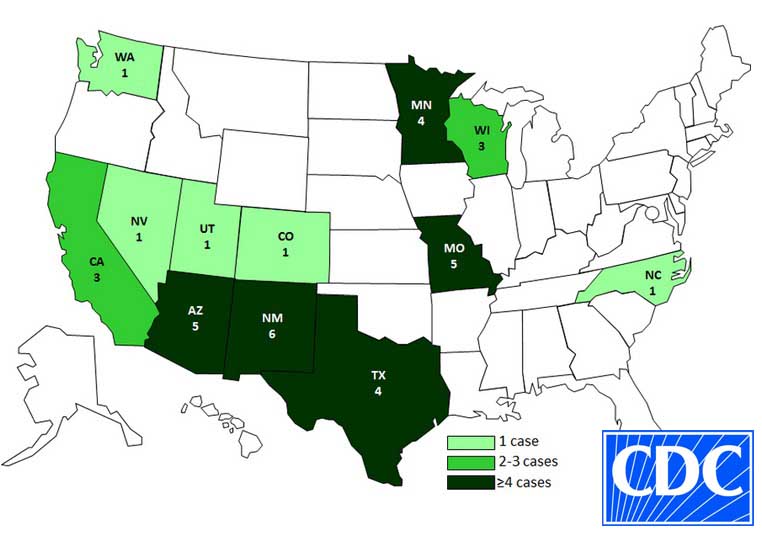

The locations of people who were infected with Listeria monocytogenes as of February 15, 2015, by consuming prepackaged caramel apples made by Bidart Bros. Apples. (Courtesy the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

Seven people died and about 35 were sickened in the outbreak that investigators tied to a specific supplier of Granny Smith and Gala apples in California, marking the first direct tie of fresh whole apples to a serious food safety outbreak.

When such outbreaks occur, the first thought is to the victims, and the second thought is to the products involved, said Bob Whitaker of the Produce Marketing Association, who moderated the session.

“Another tragedy is when we fail to recognize the outbreak for what it is, and what it is basically is a failure in our business operations.”

That breakdown in processes that are designed to deliver healthy products to consumers requires that adjustments be made, he said, to minimize the chance an outbreak will happen again. In the case of the outbreak tied to caramel apples, “there are critical lessons to be learned from this.”

Here’s a rundown of key points:

—Apples weren’t previously considered a likely source for Listeria, and intact, undamaged apples remain an unlikely cause of listeriosis. However, problem spots remain.

Research has shown that the stem end or calyx area is problematic for cleaning and sanitation, as are deep depressions in the fruit that could harbor bacteria, said Kathleen Glass, associate director of the University of Wisconsin-Madison Food Research Institute.

When the stick was inserted into the apple, in this case, it translocated the Listeria from the surface of the apple to the interior flesh.

These points provide an explanation for the Listeria in the caramel apple and highlight the potential for another outbreak “unless we look at other intervention strategies,” she said.

—The industry can only have a better understanding of the prevalence of Listeria in packing houses by adequately monitoring for it. And know that Listeria can hang around longer than you think.

Oct. 31 was the last day of operations at the California packing house where the apples in this case were packed.

That packer, Bidart Brothers, opened its doors to researchers to help determine the cause of the bacteria, and researchers were able to detect Listeria on different surfaces all the way up to the end of March, said Trevor Suslow, extension research specialist for the University of California-Davis.

“Listeria was widely distributed and highly persistent, even under dry conditions weeks later,” he said.

—Packers must consider the end use of their products.

In the case of the caramel apples, storage temperature was also an issue, with the apples stored at room temperature, enabling Listeria growth.

“We need to ask the question: What can happen to our product to convert it into food that now poses a high risk for Listeriosis?” said, Martin Wiedmann, a food safety professor at Cornell University. “You cannot rely on the consumer. You need to understand what the consumer can do with your product. I challenge all of you in the industry to start to think that way, because I think it’s very important.”

—Awareness and training are vital.

Growers and packing houses can’t simply wait for the next outbreak.

They must raise awareness, communicate with employees and offer training workshops now to prevent future outbreaks, said Ines Hanrahan, project manager for the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission.

“You can change human behavior, and if you change that, you have won half the battle,” she said.

These efforts require management buy-in, bigger cleaning crews with a motivated crew leader — all of whom love what they’re doing and recognize it’s not just a job — and more time devoted to cleaning and sanitation with a master schedule, she said.

A reward system, monetary or otherwise, such as pizza parties for work crews, can also boost performance.

“It’s really about trying to understand what it is we’re trying to accomplish, what is personally at stake for them,” she said. “If a worker understands how it relates to his family, how an outbreak could affect his family and their health, it makes a difference. And it makes them feel appreciated and like they’re not forgotten.”

—Communicate. Communicate. Communicate.

The outbreak resulted in lost industry sales of $15 million, canceled promotional events and a sea change in thinking about export risk, said Mark Powers, executive vice president of the Northwest Horticultural Council.

Seven countries took actions related to the outbreak, and two, Indonesia and Sri Lanka, stopped trade altogether.

Many of the actions fell on products that were not a safety concern, largely due to misunderstanding of the facts, Powers said.

Federal regulators, foreign embassy personnel and industry associations need to be on the same page in the event of an outbreak, sharing the same message, he said, to avoid a crisis.

Bidart Brothers shipped its apples months before packers in the Pacific Northwest shipped theirs, Powers said, yet the effects were felt by everyone.

“The product was out of the market. The response was off the charts, out of reality, but it was real, and the concerns were real,” Powers said. •

– by Shannon Dininny

Where did the listeria originate? In the field or in the packing plant? How common is this type of occurrence? It does little good to call for “more time devoted to cleaning and sanitation with a master schedule,” unless one has a good understanding of the exact nature of the problem and why it occurred in this case when this seems to be a clear anomoly.