—by Ross Courtney

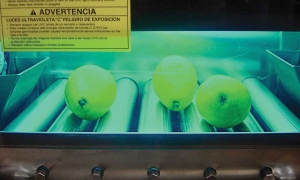

Researchers from Oregon State University and Washington State University are studying the use of ultraviolet light on fruit packing lines.

Two projects are underway to search for the best ways to use short wavelengths of UV light to reduce the incidence of fungal and bacterial pathogens that cause decay or foodborne illnesses in packing facilities.

Research has long established that UV light kills microbes. It’s now a matter of figuring out how to incorporate it efficiently and safely onto packing lines, said Claire Murphy, WSU produce safety extension specialist.

“There’s definitely a need to optimize,” she said.

Qingyang Wang, an OSU food science extension specialist, is spearheading one project aimed at answering several questions: What wavelength works best? How long of an exposure is needed? How would the light interact with sanitizers?

She is aided by Murphy, who is familiar with the practicalities of adding technology to packing facilities. The three-year project is funded by a Specialty Crop Block Grant and the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission.

Meijun Zhu, a WSU food science microbiologist, is leading the other project, which aims to gauge the effectiveness of UV systems in killing foodborne-illness pathogens and decay organisms when used alone and in conjunction with commonly used disinfectants, such as peroxyacetic acid or chlorine. Her team will test the technology on WSU’s pilot-scale packing line in Wenatchee and on two commercial lines.

Zhu’s project is funded by the research commission.

Wavelengths

The projects will tackle questions about the UV light wavelength.

Wang will compare the effectiveness of UVC light, which has a wavelength of 222 nanometers, and traditional 254-nanometer UV light. The shorter wavelengths are potentially safer for workers’ skin and eyes.

Zhu will study only the 222-nanometer UVC light.

UVC light on a packing line may sound familiar.

In 2015, Shyam Sablani, a WSU biological systems engineer, led a project to test the use of UVC light in apples and pears to control Listeria species and E. coli. On apples, he found it reduced E. coli incidence by 99.8 percent and Listeria by 96 percent. Pears had similar results.

He didn’t pursue the research further because the industry was nervous about breakable glass lights around food, he said. Today, LED lights make the idea safer, so food producers have renewed interest. He is currently collaborating on a U.S. Department of Agriculture-funded project using 222-nanometer light to improve food safety in cut lettuce.

Potential use

The research could lead to production companies installing UVC lights along their packing lines, giving the industry another chemical-free food safety tool.

One possibility is to mount a UVC light box right after the spray bar, which emits either clean water or a sanitizer, to let the moisture droplets on the fruit surface refract the UVC light for better coverage. On the other hand, that could reduce transmittance and lower the effectiveness, Wang said.

“We don’t know until we have the data,” she said.

Currently, at least two fruit packing warehouses in Washington use the UVC light on their lines between storage and packing, Murphy said.

Both have reported a slight decrease in decay, she said. In one small trial run of 30 apples, the UVC lights reduced mold, fungi and total coliforms by about one log, or 90 percent, she said. Those results aren’t bad, but when it comes to foodborne-illness pathogens, the produce industry usually shoots for a 99.9 percent reduction, Murphy said.

Wang said she added mold to the project research goals, because less literature exists about UVC light and mold.

And it’s more forgiving, Wang said. Even a reduction in mold could prevent economic waste by reducing decay. Fighting foodborne-illness pathogens, such as Listeria and E. coli, is a zero-tolerance game. UVC light will never completely remove listeria because coverage will always be imperfect.

Murphy also is involved with another packing house food safety Specialty Crop Block Grant. In that project, she will collaborate with the University of Georgia, the Center for Produce Safety and the U.S. Department of Agriculture to find which wavelengths of UVC light work best to sanitize certain colors of rotator brush rollers, one of the most difficult places to clean in a packing facility. It focuses on foodborne-illness pathogens, not mold. •

Leave A Comment