Listeria seems to like polishing brushes, dryer rollers and places under fans or blowers.

Those are among the conclusions from Faith Critzer, a Washington State University food safety extension specialist, after she and her team sampled surfaces in Washington apple packing facilities.

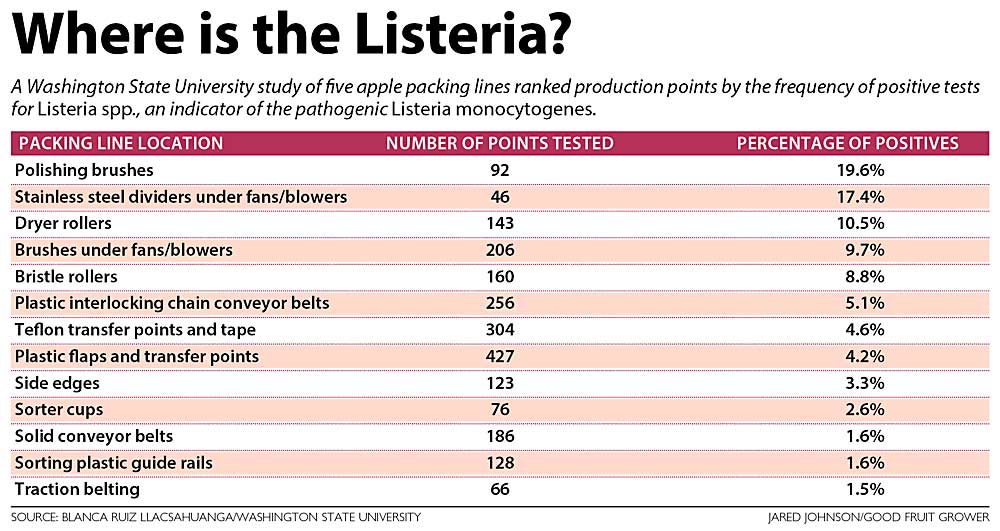

Over the course of two seasons, Critzer’s group took nearly 3,000 swabs over various locations along five packing lines; 4.6 percent of the samples were positive for listeria species, about par for the course in a variety of fresh produce studies, including avocados and tomatoes, Critzer said.

That doesn’t mean all those spots posed a risk of apple-borne illness. To gauge food safety risk, researchers and food safety technicians test surfaces for a broad category of listeria species, only one of which is Listeria monocytogenes, the particular pathogen that can cause serious and fatal foodborne illnesses in people with a weakened immune system.

Still, the results indicate where the fruit industry should concentrate its cleaning, sanitation and prevention efforts, Critzer said.

“You can’t improve unless you know where you’re vulnerable,” she said.

Critzer’s systems-based prevention project to rank the risky spots is a three-year research study funded by the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission for a total of $196,000. The final year, 2021, will focus on methods to clean these hot spots.

Packing house food safety is a heavily studied topic these days. The research commission is also supporting Critzer’s projects related to rapid tests in packing houses and dump tank water, as well as projects by WSU colleagues Girish Ganjyal and Meijun Zhu who are, respectively, studying the use of surfactants and exploring survival of listeria in ozone and controlled-atmosphere storage. Meanwhile, some of those same researchers are collaborating with the Center for Food Safety on a Washington Specialty Crop Block Grant study on dump tanks and flume water.

They all add up to more than $1.2 million in funding.

Critzer’s surface study ranked positive test frequency for 13 points throughout the packing line. Coming in first — or worst — at almost 20 percent was wax polishing brushes. They’re hard to clean. “It’s not due to lack of want,” she said.

Those were followed by stainless steel dividers under fans or blowers, at 17.4 percent; dryer rollers, at 10.5 percent; and brushes under fans or blowers, at 9.7 percent.

The good news was that many of the food contact surfaces she tested — brushes under spray bars, dump tanks and flumes, sorting brushes and cup droppers — had a positive rate of less than 1 percent.

The study also compared listeria prevalence at various times. She saw more listeria in the middle of the packing shifts than right after daily cleaning and sanitation, and she saw more listeria as the season progressed.

No surprise

Not much in the results surprised Jeremy Leavitt, food safety and compliance director for Borton Fruit of Yakima, Washington.

In 2019, the company built a new packing line with an eye toward food safety. To clean the polishing brushes, the company designed a clean-in-place system that uses high pressure water to knock away wax and debris, while an ozone rain bath keeps the bristles disinfected. Line supervisors can turn on the automated system for cleaning, even during 15-minute breaks. The nightly cleaning crews, of course, scrub it with degreasing solutions when the line is down, he said.

Meanwhile, the new drying facility uses heat and humidity control instead of fans or other forms of propelled air, also among the hot spots in Critzer’s study.

The problems pointed out by Critzer’s study are hard to fix without a complete rebuild, Leavitt said.

“If I was going to do this at the old Borton Fruit facility, we would have been tearing out equipment; we would have been down for months,” he said.

Jennifer Pulcipher, director of food safety and compliance for North Bay Produce cooperative in Traverse City, Michigan, also found Critzer’s results predictable.

“These brushes are a challenge because once you have a problem, it’s very hard to get rid of,” Pulcipher said.

When it comes to polishing brushes, for example, she instructs the company’s member packers to make them a priority: advising that they clean and sanitize the brushes daily and also remove them once a month to further rinse away debris and wax buildup — soaking them in both cleaner and sanitizer and then letting them dry completely. Then, to prevent any possible cross contamination, she advises they clean and sanitize the areas around the polishing brushes before reinstalling.

In 2019, North Bay voluntarily recalled more than 2,000 cases and two bins of fresh apples due to potential Listeria monocytogenes contamination at an apple packing facility near Grand Rapids. The company was not aware of any related illnesses. Some of the locations among Critzer’s top hits were among the culprits the packer identified through its own routine testing in that case, though Pulcipher declined to name them.

Leavitt and Pulcipher agreed that Critzer’s research shows how continuous study improves food safety over time. For example, six or seven years ago, all brushes were of equal concern in the industry, but Critzer’s study found zero positives on sorting brushes.

“It’s far less scary to know what your issues are so you can deal with them head-on,” she said. •

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment