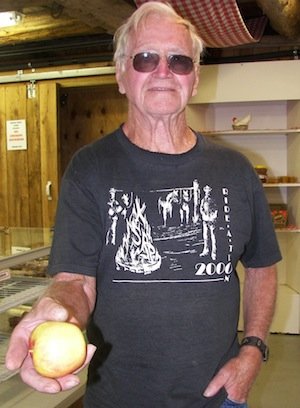

Phil Schwallier’s father-in-law, Carl May, hands out a free Honeycrisp, a trademark that won’t be there at Schwallier’s Country Basket this year.

The freezes that struck fruit crops across the eastern United States last spring threaten some growers more than others. For wholesale growers, no crop means lost income for this year. But for growers who are direct retail marketers at farm or farmers markets, this year could mean a loss of connection with long-time customers.

They were faced with a decision whether to hunt for fruit to replace their own and maintain their markets, or close up shop for the year.

Edwin Dwan, a 74-year-old former fruit grower, now consults with direct farm marketers in southwest Michigan and northern Indiana and Illinois. He flew to Washington early in June looking for apples on their behalf.

He was “trying to come up with a plan,” he said, that will allow them to have apples to sell, so he went to Washington, where growers are looking at the largest crop ever (140 million bushels on the tree and 120 boxes packed).

“Everybody east of the Mississippi is out there, and they know they’ve got a tiger by the tail,” he said. “We’re going out there with nothing and asking for a lot.”

Overall in the United States, the apple crop is smaller than usual, but Washington has apples and knows how to sell them, Dwan said. “Ninety percent of their crop is shipped some place more than a thousand miles away, so nobody’s reinventing the wheel logistically,” he said.

Still, he thinks his long connections with packinghouses in the West are very helpful. “It would be difficult for somebody without connections to just walk into a packinghouse and buy apples,” he said.

The Eastern marketers are used to selling a long line of seasonal varieties. “I asked my clients to make a wish list, and there are 32 varieties on it,” he said. “In the end result, there’ll be oddball varieties we won’t get many of, and we’ll take less or smaller amounts and divvy them up.”

A looming problem could be labor. “I’m suggesting that the western growers try to get the Michigan workers to go there,” he said. “It would be a crime to have an apple drop to the ground this year when there is such a demand for every one of them.”

At 74, Dwan is just old enough to remember the War Years, when he father and grandfather were trying every way possible to find labor to process and pack the apple crop, when labor was just not available. He doesn’t specifically recall 1945, the last time the crop was so severely damaged by a warm March, cold April combination.

“This is an event, once in a hundred years,” he said. “I’m doing this because I want to be involved in it.”

Wind machines

For some years, the Steffens Orchard Market on Fruit Ridge has served a neighborly clientele of you-pick customers near Sparta, Michigan, and it will again this year.

“We’ve got enough apples to run our market, thanks to wind machines,” Rob Steffens said. “But we will have no apples for wholesale.”

Steffens has four wind machines. “I wish I had ten more,” he said. “It costs $15,000-18,000 an acre to plant an acre of apples. That’s a huge investment, and we need to do all we can to protect it.”

The Steffens normally grow some 200,000 bushels of apples on 280 acres. “Our farm market is small; we probably only sell 20 bins of apples each year.”

The orchard’s Web site announced it would delay opening until August 18, since there are no cherries, either, to open the fruit season with. The market sells other products, including you-pick pumpkins, which are doing quite well this year.

It’s going to be a tough year for processors, migrant workers, and fruit growers who didn’t have crop insurance, Steffens said. And the state of Michigan is in for a surprise later this year when the normal revenue from payroll and sales taxes fails to show up, he added.

New York

At Eshleman Fruit Farm in Clyde, Ohio, Richard Eshleman said, “I hope we can source fruit for our farm market customers and those that depend on us for fruit,” he said. “We normally buysome apples from Michigan and New York, and we’re hoping to find enough in New York to fill our needs.”

Eshleman sells more than half of his crop locally, and more than half of that goes to other direct farm marketers who buy his fruit for their markets. They sell about 20 percent of their crop to you-pick customers who come for the experience as much as the fruit The Eshlemans update their customers through Facebook and received a lot of sympathetic feedback from customers. “We have not had such a reduced apple crop since 1977,” they wrote.

Fruit Ridge

Phil Schwallier, the Michigan State University Extension fruit educator who works on the Fruit Ridge area north of Grand Rapids, also operates with his family a farm market called the Country Basket. Their trademark offering these last few years has been Honeycrisp apples.

“We’ll be open,” Schwallier said. “We have only 1 or 2 percent of an apple crop, but we’ll probably buy apples from elsewhere on the Ridge or from the Traverse City area. There are some apples there. We also have pumpkins and baked goods.”

Tim and Cindy Ward at Eastman’s Antique Apples in Wheeler, Michigan, aren’t sure what they’ll do. They normally offer dozens and dozens of unique apples at their retail spot at the Midland Farmers Market. They have some apples, but they may just close shop for the year and use what they have for cider.

end

Leave A Comment