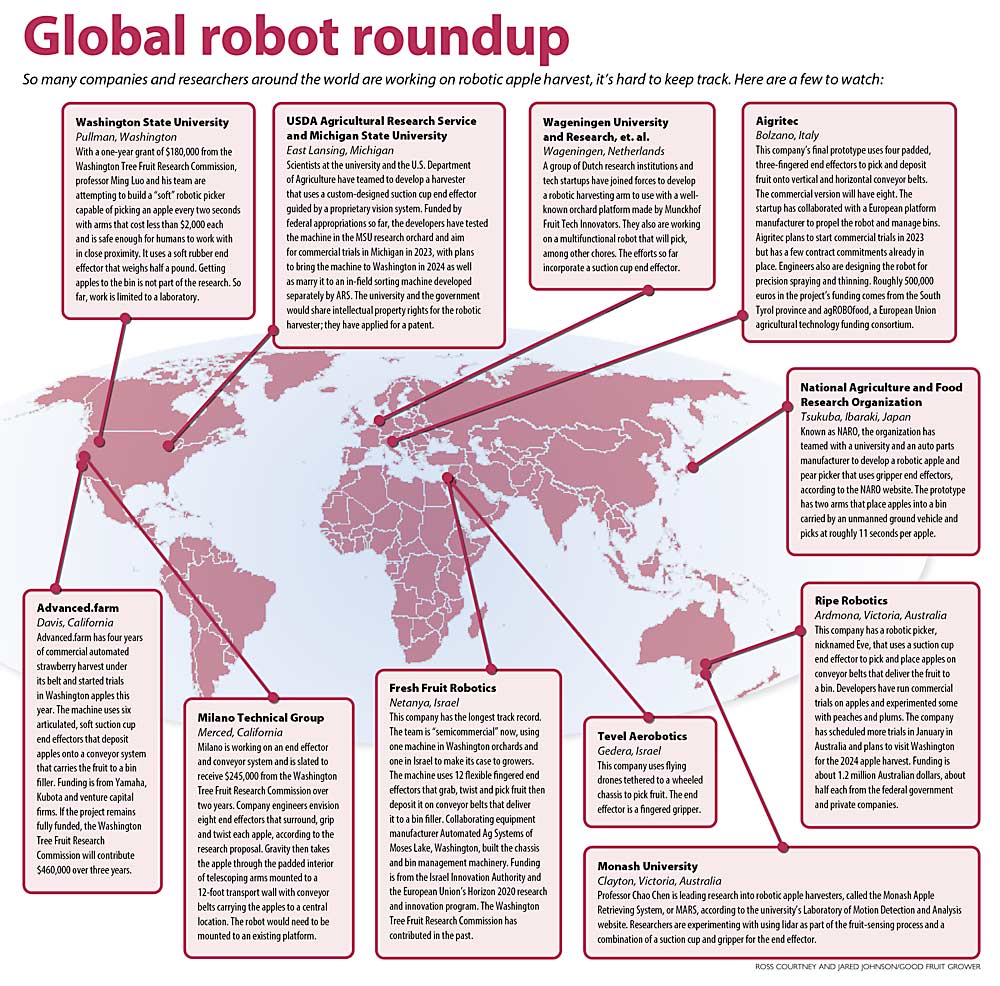

A global cadre of agricultural tech startups are trying to build an apple-picking robot.

Driven by increasing wages, overtime mandates and a scarcity of labor, at least 10 companies or research groups are on the development path somewhere between prototype and commercialization. Some of them are progressing quickly, and all use artificial intelligence and machine learning, which by definition means improvement with every apple picked.

It’s only a matter of time before one or more is ready for industrial-scale use, backers said.

“I think in the next two or three years, maybe five,” said Keith Veselka, a co-owner of NWFM farm management company and member of the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission, which funds some of the efforts. “You know, it’s good having multiple people invested in the problem.”

In Washington, the two current leaders are Fresh Fruit Robotics, which began conducting trials in the state in 2019, and relative apple newcomer advanced.farm.

Advanced.farm of Davis, California, purchased the prototype from now-defunct Abundant Robotics and tinkered with the machine, but in the end the company built its own chassis, arms, end effectors and vision system, said Peter Ferguson, business development director. A few of Abundant’s pieces were donated to one lucky local high school robotics team.

The founders of advanced.farm notched their first commercial victory building robots to clean solar panels in the surging green energy market of California. Switching their attention to farming, they started their new company in 2018 and now have 16 harvest machines leased to five commercial strawberry farms. They train field workers how to operate them with an operations staff hovering nearby for troubleshooting.

They chose apples as their next project because of the industry’s hunger for a robotic solution and growers’ willingness to modify orchard structures, Ferguson said. The research commission has helped fund their development at $460,000, assuming the grant continues over the three-year plan. The company ran commercial trials on several varieties this year in the Columbia Basin and reached peak pick rates of 1,000 apples per hour.

Fresh Fruit Robotics, or FFRobotics, has the longest tenure of the bunch. Founded in 2014, the Israeli company has one machine in Washington, where it has completed commercial trials for the past several years. In 2022, they picked Fuji, WA 38 and Gala on a limited scale in a Columbia Basin orchard under a custom harvest contract for Stemilt Growers.

Each variety requires software tweaks, said Avi Kahani, CEO and co-founder. WA 38, for example, needs extra gentleness to avoid damaging spurs, a problem for hand pickers, too. Gala tolerates more aggressiveness. Honeycrisp bruises easily.

To help solve those problems, FFRobotics has recently added a flexible “wrist” at the end of each of the harvester’s 12 telescoping arms, to give the three-fingered grippers a more centered fit around each apple.

The company claims it can pick eight to 10 times as efficiently as a human.

Eventually, FFRobotics intends to use the same machine, with different end effectors, for thinning, pruning and pollination. Washington State University researchers, who have been working on a robotic pruner, are consulting on those topics, Kahani said.

The landscape

Other robotic harvest efforts come from university teams and companies including Ripe Robotics of Australia, Aigritec of Italy, Milano Technical Group of California and many more. Most are coalescing around robotic arms — though using different gripping approaches — guided by a computer vision system.

The founders vary in their farming and orchard backgrounds. Kahani managed an orchard in the 1980s in Israel and has been working in Washington for several years. Advanced.farm has strawberry experience and spent the 2021 apple harvest watching and asking questions, even testing their grippers from time to time. Hunter Jay, CEO of Ripe Robotics, purposely took up residence in an Australian orchard worker housing facility. The university-based efforts have fruit researchers who know their growers well. Aigritec is located near a horticulture research station in the South Tyrol province of Italy, where about 10 percent of Europe’s apples grow in a compact geographical area.

Websites of the private companies feature flashy promotional videos that would rival a Super Bowl automobile commercial, but most companies eye a service or lease business model — at least at first. Though growers are anxious for robot harvesters, they won’t want or be able to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars on complex, unproven machines.

“At this point of time, until it’s proven, and everybody’s satisfied with the result, it will be a service,” said Kahani of FFRobotics, which up until two years ago had been eyeing individual sales. “It will ease the penetration from one side and reduce the burden of selling a very expensive machine that nobody knows.”

For the most part, end effectors have fallen into two categories: either a vacuum-powered suction cup or prongs that grip apples like fingers. Gone is Abundant’s attempt to suck apples through a tube robotically, though a harvest-assist platform under development by Washington and Michigan partners still uses vacuum hoses.

Tevel Aerobotics, another Israeli company, is an outlier, using drones with gripper arms tethered to a rolling chassis that holds the bin. The company declined interviews with Good Fruit Grower.

“We’re just starting off in the area, and it’s too soon to have media visit us,” said Ittai Marom, general manager.

Tevel held a commercial demonstration for some Washington growers on the research commission this fall near Moxee, though the commission is not funding the company’s work.

Milano Technical is backed by the research commission and has been communicating with commission representatives, though aside from introductory emails, company officials did not reply to Good Fruit Grower’s interview attempts.

The research commission also currently supports advanced.farm and WSU, and it and has funded FFRobotics in the past.

The ashes of Abundant

Current momentum belies the pall cast over the industry’s robotic hopes by the liquidation of Abundant Robotics last year. The Silicon Valley company, heavily backed by venture capital and the research commission, appeared to be the front-runner to full commercialization and had multiple years of industry-level trials in Washington under its belt. Several principals of Northwest fruit companies also had money tied up in the company.

“We kind of all gasped,” said Jeff Cleveringa, head of research and development at Starr Ranch Growers and a member of the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission.

But that failure fertilized the proverbial ground, Cleveringa said. Growers, remaining robotics players and newcomers all learned a lot. For example, the pass-through bin handling system familiar on many orchard platforms seems to work best, while engineering and machine learning has improved. Also, growers have modified horticultural techniques to make apples accessible and visible to computers. Occlusion — fruit partly obscured by limbs and leaves — remains one of the biggest technical hurdles.

“While it was bad for them (Abundant), it really did advance the industry,” Cleveringa said.

Two pennies per pick

Most robotics companies hedged their answers about how fast they can pick and at what cull rate, so far. They were reluctant even to share their efficiency goals. For that matter, the fruit industry itself doesn’t know what to expect.

“We’re trying not to wedge them into, ‘It has to be this fast,’” Cleveringa said.

For a benchmark, the research commission has been using 2 cents per pick, Cleveringa said. Currently, that’s how much it costs to hand pick each Honeycrisp apple, though that will go up over time. All other metrics will depend on the size of the grower, the pace of the machine and how many machines the grower is willing to contract.

Despite their hustle, most developers don’t consider the robotic harvest arena a “race.” There is room for multiple players, the same way farming has room for multiple tractor brands.

If anything, it’s a race against time, not each other, said Veselka of the research commission, to ensure food security for a growing population. Hand labor simply won’t keep up. “There is a clock ticking,” he said.

Researchers like to be first and cutting-edge, said Renfu Lu, the principal investigator of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Research Service and Michigan State University robotic harvest project. But everyone will learn from each other, and the final product may end up splicing together ideas — intellectual property rights allowing, of course. “It’s not as simple as, ‘You win, I lose,’” he said.

The first one to reach full commercialization will reap some rewards, but, geographically, one company would not be able to scale quickly enough to reach the entire world before others commercialize, said Elia Bruni, co-founder and CEO of Aigritec in Italy. Also, companies will have to painstakingly check data, costs and speeds before anyone adopts anything.

Bruni likened the robotics marketplace to a game, more than a race. He’s competitive but still gets excited when other companies make gains.

“It’s fun,” he said. “In the end, I think it must be fun.”

—by Ross Courtney

Editor’s note: This story was updated to correct the spelling of Tevel general manager Ittai Marom’s name. Good Fruit Grower regrets the error.

Leave A Comment