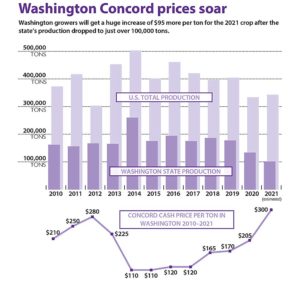

Over the past decade in Washington, Concord growers have been pulling out more grapevines than they’ve been planting. But a strong price rebound, combined with the advantages offered by mechanized management, compared to other fruit crops, could spur some modest, modern planting.

Which raises the question: What does a modern Concord vineyard look like?

Washington State University viticulture professor Markus Keller said he recommends planting today exactly how he planted in his own research block at WSU’s Roza research farm in Prosser nearly 20 years ago as a demonstration of mechanized management.

“It’s worked out pretty well,” he said. “We produce above the industry average with very, very minimal labor.”

Keller recently published one paper and has another in process with conclusions from long-term trials on optimum vine planting density and deficit irrigation strategies. The research was funded by the Washington State Concord Grape Research Council.

“When I started at WSU 20 years ago and met with Concord growers, they said there were three things you could not do: You cannot use drip irrigation, you cannot use mechanical pruning, and you cannot use cover crops,” Keller recalled. “So, I planted a vineyard where we did all of that as a demonstration block for minimal labor inputs, and it’s still going strong. We have to check the irrigation from time to time and inject the nitrogen, but in the vineyard itself, there is no hand labor.”

While mechanized pruning has been widely adopted over the intervening years, Keller’s findings on optimum planting density may become more relevant now if growers are planting. He compared two different row spacings and four in-row spacings, ranging from 400 to 1,800 vines per acre.

“My hypothesis was when you want to build a vineyard of mechanized production, you need to plant it more densely,” he said. “Of course, we found the exact opposite.”

Common wisdom holds that planting grapevines close together forces them to compete for water and nutrients in the soil, creating desired stress in wine grapes for example, but Keller found the Concord vines actually compete for light.

“They sense other plants are around and they start competing by investing all their energy into more leaves and less fruit,” he said.

Vines planted with the tightest in-row spacing, just 3 feet between vines, produced significantly less than the other plantings at spacings of 6, 9 and 12 feet, after the vines were fully established in the fourth year — a 38 percent reduction on average over five years. The wider spacings were all comparable.

“You can easily plant at 9 by 9 and have the same yield as 6 by 8,” Keller said. “It turns out that over time, yield is a linear function of the space available for each plant …. It just takes an extra year to fill the length of the wire if you plant with more than 6-foot spacing.”

With vineyard life expectancy upward of 30 years, growers may find it makes more sense to save nursery costs and plant at lower density.

Another research project looked at optimizing irrigation. As with mechanical pruning, many growers have switched from furrow or sprinkler irrigation to drip since Keller launched his research project. The findings confirm not only that drip performs well, but also that vines can withstand a fair amount of deficit irrigation.

“We can cut water 25 percent and have no yield penalty,” he said. That’s a 25 percent reduction compared to keeping soil moisture content matching the evapotranspiration (ET) rate. “It turns out that juice grapes max out at 75 percent of capacity. We can irrigate from fruit set to harvest at 75 percent and have the same yield year over year for seven years.”

Keller said it’s important that he did this irrigation work in the context of his mechanically pruned vineyard. Mechanically pruned vines tend to produce larger canopies than traditionally pruned vines, so it was reasonable to assume they might need more water. But it’s good to know they don’t, especially as climate change is likely to lead to more short water years in the future.

When it comes to deficits, it’s about timing, Keller said. To maximize cropping potential, Concords need full water early, from bud break through the onset of ripening, but then growers can cut back during the ripening process with no impact on yield. Growers can estimate evapotranspiration and vineyard water needs through AgWeatherNet’s estimates or by installing soil moisture sensors, he said.

Keller also recommends that growers plant a cover crop. In his vineyard, he took what he calls the “lazy approach” and let the weeds grow on the former cornfield site, just spraying herbicide under the vine rows. Or, you could call it site-adapted cover cropping, he said. Over time, the weed population became more diverse, which offers other benefits. For instance, grasses release compounds into the soil to help their own roots consume iron, reducing chlorosis in grapevine roots.

Lastly, he recommends starting with clean plants.

“I would not even plant a juice grape vineyard with noncertified plants,” he said, as virus-infected materials could pose a risk to neighboring wine grapes as well.

Whether juice grape growers will need to turn to rootstocks for future planting, as Washington wine grape growers are in light of widespread phylloxera findings, remains to be seen, Keller added. Concord does have one Vitis vinifera grandparent along with its phylloxera-tolerant Vitis labrusca heritage. While there’s been no indication of phylloxera damage in Washington’s juice grape vineyards, he noted that in New York and Michigan, all the juice grapes are grafted.

His research vineyard is poised to answer rootstock questions as well, should they arise, Keller said. He planted grafted vines some years back but never had a need to evaluate them.

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment