—by Kate Prengaman

Growers face more vineyard disease challenges than just powdery mildew.

That’s why the scientists behind the Fungicide Resistance Assessment, Mitigation and Extension Network, or the FRAME Network, pushed to expand the project’s scope with its second round of grant funding.

“Our first project was all powdery mildew all the time,” said Michelle Moyer, the viticulture extension specialist at Washington State University and project leader of FRAME 1 and 2, both of which are funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Specialty Crop Research Initiative. “We were really hyper-focused on FRAC 11 fungicides so we could get into the weeds on genetic mechanisms of resistance.”

Now, with a second round of funding to stretch into 2028, the scope of the project is both expanding and contracting.

The expansion includes two other critical fungal diseases, downy mildew and botrytis bunch rot, and the primary fungicides growers rely on to control them. The contraction comes in the scope of work, which will be more focused on how growers use resistance information to improve disease control and be better stewards of fungicides, Moyer said.

“We are expanding to other fungicide groups that are important to those three pathogens,” she said.

The research effort that started in 2018 focused on powdery mildew resistance to FRAC 11 fungicides. That was a natural starting point, because one consistent, documented genetic mutation gives rise to resistance, making it easier to study, Moyer said. (The FRAC codes denote different fungicide modes of action, as laid out by the Fungicide Resistance Action Committee.)

“Rapid detection was a really big win with FRAME the first round. You could send us a sample and we could turn it around quick,” she said. That rapid testing allowed growers to make timely management decisions and select other products if they had a FRAC 11-resistant strain of powdery mildew in their vineyards.

But such genetic tests only work when they are built on known markers, and powdery mildew’s resistance to other fungicidal modes of action is not as straightforward.

Through this second project, researchers at WSU, Michigan State University, the USDA Agricultural Research Service in Corvallis, Oregon, Cornell University, the University of California Cooperative Extension-Napa County, and the University of Utah will explore the best tools and techniques for rapid resistance screening and the best approaches for efficient sampling.

An effective tool comes down to speed and cost. Traditional resistance testing done by university scientists can’t help growers make decisions within a given season. Researchers first must cultivate the strain of powdery or downy mildew on grapevine leaves or clusters (it won’t grow on a plate in the lab) and then try to kill it or prevent it from making the next generation by applying various concentrations of each different fungicide.

This takes prohibitive amounts of time and resources to be accessible for growers to make in-season management decisions. Hence the push to develop new screening approaches.

“The ultimate goal for us is to create tools that can be more easily adopted by regional diagnostic labs, such as rapid genetic tests, and to build awareness and demand for those services,” she said.

Think about it this way: The researchers are not trying to solve the problem of fungicide resistance. They aim to solve the problem growers face when they pay for a product, apply it, and still lose the crop to the disease.

“Fungicide resistance in and of itself is not that big of a problem — resistant individuals in a population naturally occur. We only really care about fungicide resistance when it builds up in a population to where it results in a control failure,” she said. “Crop loss is the problem.”

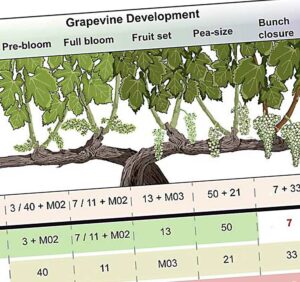

And while there are many, many fungicides on the market, only a handful of key modes of action labeled for vineyards exist, and growers must rotate them while hitting critical management windows.

“It’s a hamster wheel of losing products to resistance,” Moyer said, also noting the subsequent crop loss. “If we can identify resistance early, if we can learn more about how resistant fungal populations build and move and change within a managed vineyard, we can do a better job at avoiding crop loss due to fungicide resistance.” •

Leave A Comment