Erica Bland, a fourth-generation pear grower in Cashmere, Washington, grew up on her family’s orchard and has been working there full time for nine years. She’s the main tractor driver. She supervises work crews, manages payroll and stars in promotional videos produced by her sales team.

However, Bland — and many young growers like her — did not officially count as a farmer until the most recent federal Census of Agriculture results were released last year.

“My-age farmers are kind of in the same boat, where we are not called the owner, but we are kind of sliding in to take over our family’s farms,” Bland, 31, said.

She’s among a new wave of agriculture producers that received recognition in the latest U.S. Department of Agriculture count of all things farming, thanks to a tweak in methodology that collected demographic information from a wider base of decision-makers at each farm, instead of just a single “principal” producer. The change served to broaden the definition of “farmer” for a changing agricultural landscape.

The survey also asked for age, race, years-on-farm and several other details for up to four “producers” on each farm, instead of three. In 2012, Bland’s parents did not list her as one of them; in 2017, they did.

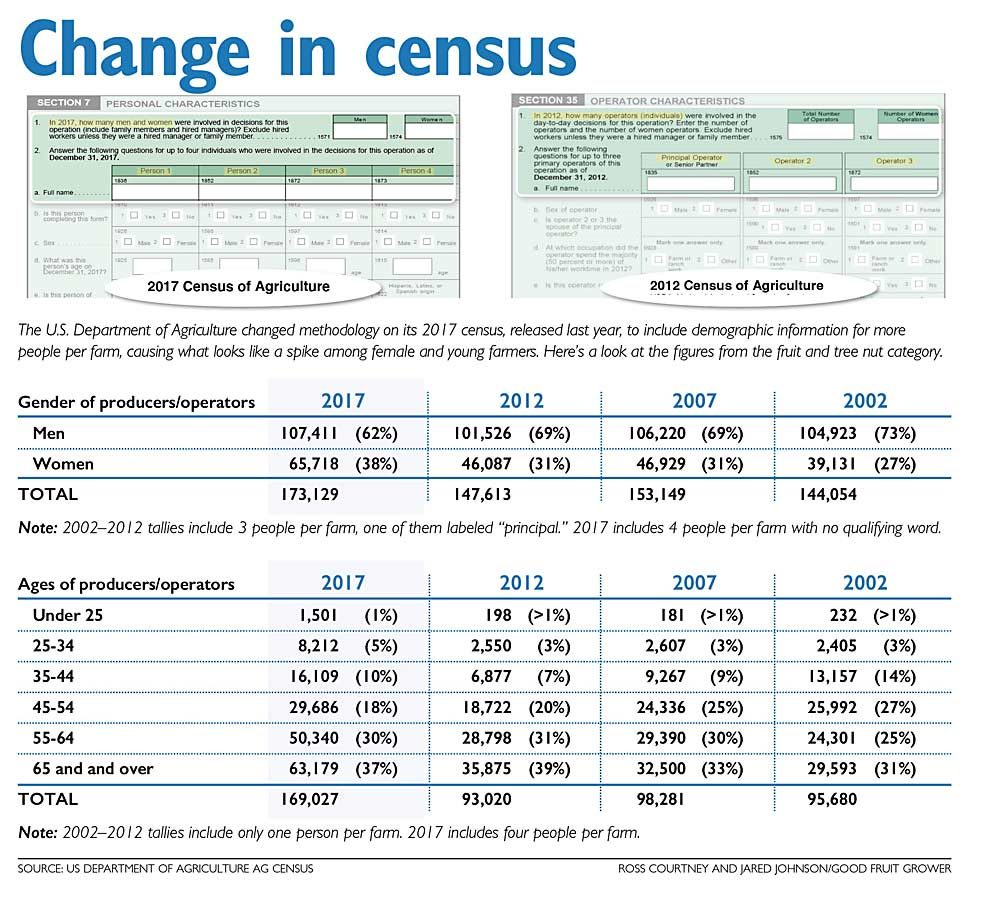

The upshot of the change is a lot more producers overall, and a larger share of young farmers and women.

Chart: Ross Courtney and Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower

Under the new methodology, the tree fruit and nut industry had almost 66,000 female producers in 2017 but only 46,000 in 2012. Nearly 20,000 women did not suddenly take up the business in the past five years, but those women working in the industry are now on the USDA’s radar. Likewise, in 2017, there were 16,100 growers ages 25 to 34 in the industry, about 8,900 more than five years ago.

That was the goal, said Virginia Harris, a statistician for USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service, which tabulates the census.

The agency changed its questionnaire to accommodate requests from industry groups to count a wider array of people involved with farming, not just one principal operator. The old way left agricultural agencies and businesses with an incomplete picture of their customer base.

“Customers are all the people who are making decisions for that farm,” Harris said.

The National Young Farmers Coalition was among the groups that sought the changes.

“The old model was excluding a lot of people who were making decisions,” said Erin Foster West, the western campaigns director for the New York-based organization.

And it’s not just about women or young people, she said. Some farms among their members are operated by two business partners, not a family headed by dear old dad. Farming chores have changed, too, with food safety, pesticide paperwork and payroll becoming full-time jobs in and of themselves.

Sarah Lott Zost also now gets to claim farmer — or producer — status at her family’s Bonnie Brae Fruit Farms in Gardners, Pennsylvania. The 28-year-old was a seasonal worker in 2012 but has since taken on a variety of responsibilities — H-2A management, food safety, camp inspections, production records and payroll. It was even her job to fill out the 2017 census. This spring, after winter meetings and tours, she revised her family farm’s planting plan and supervised it.

She thinks the change makes sense.

“When the definition of who counts as a farmer or producer is limited to the top … people on any operation, you arbitrarily limit who gets counted,” Lott Zost said. Broadening the data collection will help the overall industry, which today includes many groups aimed at supporting young farmers. She is the co-chair of the Young Grower Alliance, an educational network of Penn State Extension.

In Washington, Bland worked most of her life in the pear orchard under the guidance of her father, Vince, and mother, Lesa. Lesa does the accounting, as well as bookkeeping for neighboring orchards, while Vince handles most of the horticultural work. Bland’s fiance also works full time at the farm.

Bland has begun leasing her own small plot, partly to establish her own career but also to qualify as a member of the board of directors for Blue Star Growers, the packing cooperative to which her family brings fruit.

The irony of Bland’s newfound census recognition is that she has been acting as the “face” of her family’s Cozy Cove Orchard for a few years now. It started with short videos for Rainier Fruit, Blue Star’s sales company, showing her driving tractors and working in the office. Rainier also tapped her as a spokeswoman for Pears for Pairs, a charity sock drive with Hanes. The Pear Bureau Northwest used videos of her in marketing. Now, New York-based grocery chain Wegmans Food Markets has been talking with her about their own videos.

All the publicity only cements her role as a farmer in the eyes of buyers and shoppers.

“That’s the new age … we live in, people want to know where their fruit comes from,” Bland said. •

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment