Washington State University’s Decision Aid System, the online portal that helps growers time their orchard practices, has a new leader and new features heading into the 2021 growing season.

Dave Crowder, an entomologist at WSU’s main campus in Pullman, has taken the helm of the Decision Aid System, or DAS, after Vince Jones stepped down in January. Jones, an entomologist at the WSU Tree Fruit Research and Extension Center in Wenatchee, is retiring this spring.

Launched in 2007, DAS runs computer models for pests, diseases, horticultural disorders and other seasonal orchard factors based on weather data and crop protection guides to … well, aid Northwest tree fruit growers making orchard decisions. The system is used by about 300 people on more than 90 percent of Washington tree fruit acreage.

In routine surveys, growers have told DAS administrators they save $75 per acre compared to what they would spend on time and materials without DAS information, which adds up to nearly $20 million per year, Jones said.

The future of DAS depends on marrying its models to advances in data and automation, Crowder said. More growers are installing their own sensors, camera traps and weather equipment, which, if linked, would give DAS the ability to provide even more customized information.

“It’s going to be going more and more to big data,” Crowder said.

A couple of relatively new tools await growers logging on this spring.

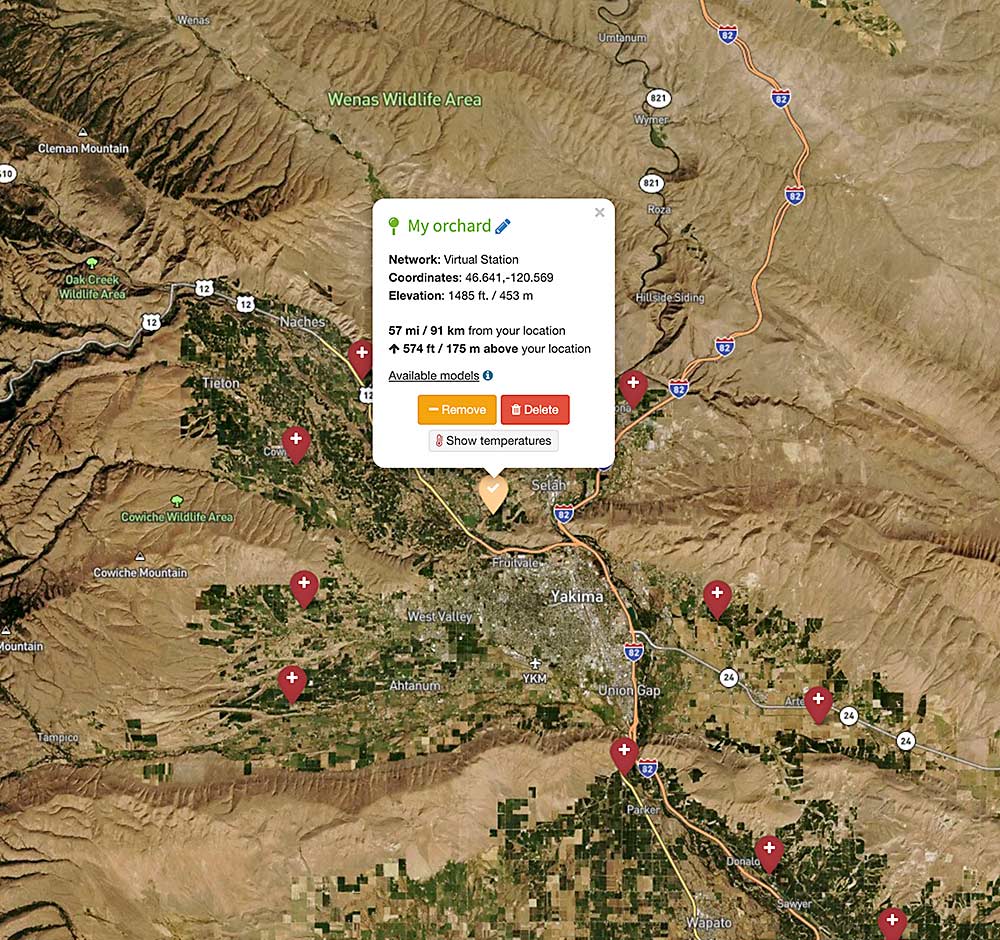

One is virtual weather stations, which give a farmer the ability to drop a pin on a digital map and receive conditions and models for that block, rather than from the nearest AgWeatherNet station 5 or more miles away. To do this, the university subscribes to Weather Source, a climate data platform that interpolates (a method to estimate new data points from the range of known values) information from a variety of stations and satellite data to create a grid that factors elevation and proximity to geographical features, such as rivers.

This year, DAS also has new models for two species of green lacewing, allowing growers to time their applications to minimize harm to the good bugs but maximize effectiveness against the pests, Crowder said. The university will add more predator models over time.

Last year, DAS administrators added models predicting how forecasted wind, rain and temperature will affect codling moth trap catch counts and a spray record evaluator that lets growers estimate effectiveness in hindsight. This year, the evaluator will add a future forecast element, Crowder said.

Wish lists for the future

Dave Gleason, a horticulturist for Kershaw Fruit in Yakima, relies heavily on DAS for a variety of orchard menaces, among them the time sensitive and potentially costly risks from codling moth and fire blight.

He appreciates DAS’ steps toward interpolated weather information and integration with the rest of agriculture’s new data-crunching tools.

“I don’t think it’s ever too much,” he said.

His wish list for the future includes more insect models, both for pests and beneficials.

“Ultimately, that helps you spray less,” Gleason said.

Teah Smith, an entomologist and agricultural consultant for Zirkle Fruit, uses DAS models weekly, sometimes daily, to prepare herself and her team for scouting, choosing pesticides and other management decisions. She also is a big fan of the pesticide spray record evaluator.

Smith wants DAS to remain the top tool for predictive analytics, even as private technologies for precision agriculture advance. The industry already trusts DAS, she said. She sees an era of DAS amalgamating information from AgWeatherNet stations, interpolated data and grower-owned equipment — if trustworthy — to provide ever-more accurate and hyperlocal information.

She also hopes DAS integrates more with AgWeatherNet in the future.

“The tree fruit industry has been asking the two to collaborate for years, as it would be in the best interest of the industry and the networks,” said Smith, a beta user and member of an industry advisory board for DAS.

AgWeatherNet also has seen some change in recent years. Soil scientist David Brown became the new director in late 2018 and has been working to upgrade network stations and connect new grower-owned stations into the network. Such privately owned stations do not run DAS models at this time.

The founder reflects

Jones, the entomologist who founded DAS, likes the idea of integrating, though he cautioned that simply knowing a temperature in an orchard block doesn’t by itself translate to more precise control. Insects move around and temperatures on the reflective surface of tree bark are way hotter than ambient air temperature, for example. Models are designed to give estimates.

“The absolute temperature in my orchard isn’t as important as people think,” he said.

Jones believes Crowder’s background in spatial ecology lends itself well to the interconnected future of DAS. Crowder’s techniques could add geographical and abundance information to the phenological models that have been DAS’ mainstay for more than 10 years, helping growers predict where and when outbreaks might occur and how much damage they might do.

For example, oriental fruit moth, a pest in the southern part of the state, is a growing concern that is currently not modeled on DAS. Spatial analysis could help create a map that predicts the moth’s spread year-to-year over the rest of the state. It could do the same for pathogens, such as X phytoplasma or little cherry virus.

“I really think that Dave is going to bring some cool tools,” Jones said.

Jones retires with a lot of pride in DAS, which helps growers anticipate problems during their busy season instead of just reacting to them, he said. It integrates with management tips and insecticide recommendations and includes 43 models related to tree fruit. (DAS also is expanding into the potato industry this year.)

“It is the best system in the world, by far,” Jones said. •

by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment