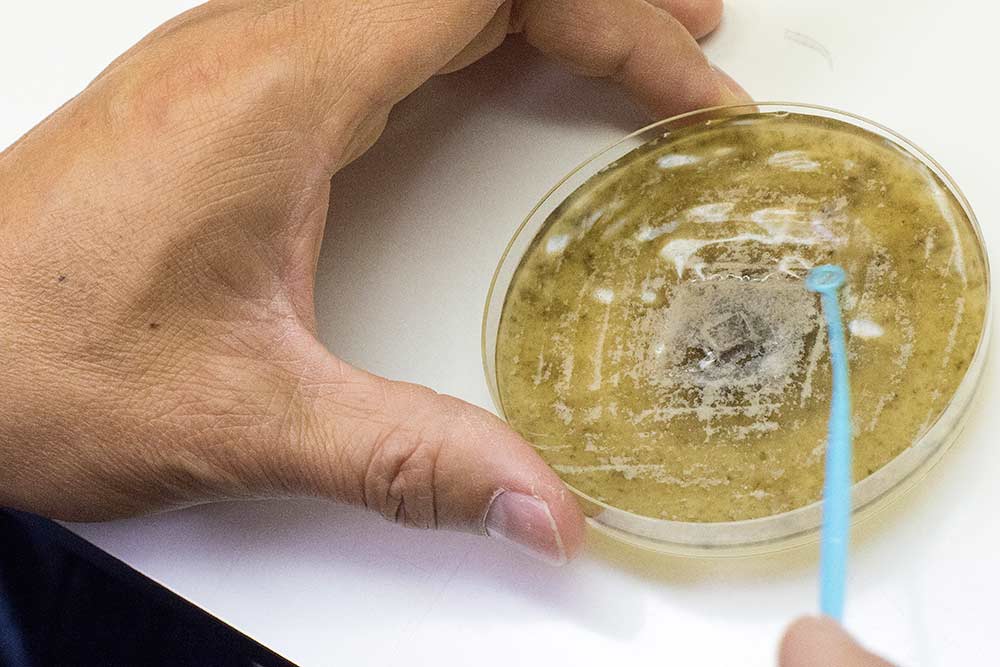

Hannah Webb inoculates Bing cherries with Botrytis cinerea fungus spores along with Jae Kwak, left, and Richard Kim, right, during natamycin trials in mid-June, 2016. Over four years ago, Kim and colleagues began conducting trials that found the fungicide helps prevent postharvest fungi in pome, stone, cherries and citrus fruits. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

For decades, food companies have used natamycin as a preservative in meats, cheeses and baked goods. Though the compound gets its share of controversy, it’s been relatively safe and effective.

Now, a Dutch chemical giant and Pace International of Wapato, Washington, are teaming up to use the same substance in the fruit industry as a postharvest fungicide with virtually zero propensity for resistance.

It may even qualify for organic certification on apples, pears, cherries, stone fruit and citrus, though one researcher cautioned that researchers still have a lot to learn about the product.

So, Good Fruit Grower asked the obvious question: Why did no one think of this before?

Turns out, they did.

The Dutch company Royal DSM that makes the natamycin tried the compound, often called pimaricin, on fruits and vegetables in the 1970s and 1980s.

It worked in the lab, but the company tabled the idea because costs were too high and demand was low for nontoxic alternatives to the synthetic chemicals that were commonly used at the time.

Fast-forward 30 to 40 years and the world now craves such softer approaches to disease control, including fungi.

“There has been a growing interest in using natural fungal biocontrol agents supported by consumers. Fruit packers are much more willing and accepting natural alternatives to synthetic fungicides,” said Richard Kim, director of plant pathology for Pace International.

The tree fruit industry currently uses synthetic chemicals pyrimethanil, fludioxonil, thiabendazole and difenoconazole for various rot diseases by drenching in a dump tank, fogging in cold storage, waxing on the packing line or spraying on the packing line, said Mike Willett, manager of the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission.

Resistance development is a concern for all of them.

That’s why biorational, or nontoxic, substances such as natamycin may provide another valuable option for disease control. “That’s good to have more tools in the mix,” Willett said.

No resistance

Rows of slightly overripe Bing cherries dry on a rack before Richard Kim inoculates them. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

Natamycin may lead to no resistance at all, ever, Kim said.

In a 2009 report, the European Food Safety Authority concluded “there was no concern for the induction of antimicrobial resistance.” The organization provides scientific advice to European nations.

Natamycin has a different mode of action than the synthetic chemicals currently used to control blue mold and gray mold in pome fruits; brown rot, gray rot and Rhizopus rot in stone fruits; and green mold and sour rot in citrus fruits. It interrupts the formation of cell membranes, a fundamental part of any organism’s reproduction.

Fungi can’t circumvent that. In contrast, synthetic chemicals block certain growth pathways and the fungi usually find a way around it to grow and survive over time.

Kim’s tests at the Pace laboratory showed natamycin to be just as effective as fludioxonil on gray mold and blue mold on apples, he said at the Pace postharvest conference in May in Cle Elum, Washington.

What’s more, natamycin seemed to be the only thing that offers any control for Mucor rot, which affects both apples and citrus.

In cherry trials during the summer by Kim and Jim Adaskaveg, a plant pathologist from the University of California-Riverside, natamycin proved as efficacious as fludioxonil in controlling gray mold, brown rot and Rhizopus rot.

The chemical also worked in mixtures with synthetic chemicals, he said. To reduce resistance problems, growers often are advised to rotate and mix the chemicals they use for diseases and pests.

Expanding uses

Soft Bing cherries inoculated with Botrytis cinerea fungus spores. The cherries are one week beyond commercial grade maturity and are part of a natamycin trial of cherries during several different stages of maturity. Botrytis cinerea begins to show signs two to three days after infection. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

DSM thought of natamycin as a postharvest fruit fungal control about five years ago and requested screens of their biorational compound by Adaskaveg and then Kim.

It’s derived from the bacterium Streptomyces natalensis, first isolated in 1955 in soil samples in Natal, South Africa.

The food industry has used it as a preservative for decades and has never encountered problems with resistance.

“It’s proven very safe, very effective,” Kim said.

Meanwhile, Dutch chemical and nutrition company Royal DSM started exploring the use of natamycin on mushrooms and pineapples.

Pace began working with DSM, the largest producer of natamycin, to make the compound for fruit. Pace has commercialized the product under the trade name Biospectra 100 SC.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency granted registration in August this year for postharvest use of natamycin on citrus fruit, pome fruits, stone fruits, cherries, avocados, kiwis, mangos and pomegranates.

Richard Kim creates a suspension of Botrytis cinerea fungus from an in-house sample of the fungus stored at Pace International’s lab. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

The company also has applied for organic certification and expects to be on the April 2017 National Organics Standards Board discussion agenda.

Natamycin has already been registered for use on organic mushrooms in Canada.

One hurdle, however, is that natamycin may not be compatible with certain sanitizers required by the new Federal Food Safety Modernization Act, Kim said. Pace is still testing.

Pace is a chemical development company that makes a wide array of treatments for the fruit and vegetable industries. The company is a subsidiary of Valent BioSciences Corporation, a Japan-based Sumitomo Chemical Company.

Natamycin worked on a variety of fungal diseases for cherries and citrus fruit and never led to resistance in his bioassay tests, Adaskaveg said. He then helped DSM and Pace develop a formulation he thought would work on the market.

The product is exempt from the EPA’s maximum residue level restrictions.

He cautioned that researchers still have a lot of questions about the product. For example, it is effective on a broader spectrum of fungal decays on cherries and citrus than it is on apples and pears, on which tests yielded inconsistent results for managing Penicillium decays.

“There’s kind of a quagmire of questions that we have,” he said.

However, he believes the compound will help out the fruit industry in a safe way.

“It is a remarkable fungicide, so I don’t want to downplay it,” he said. •

Richard Kim inoculates Bing cherries at Pace International’s labs in Wapato, Washington. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment