—story and photos by Matt Milkovich

It was a topic both spoken and unspoken at the International Fruit Tree Association’s 68th annual conference and tours in Rochester, New York, in February: How are apple growers surviving the current era of low profits and high input costs?

Western New York growers are seeking efficiencies by maximizing fruit color, quality and yields, which requires a lot of forethought and horticultural labor. IFTA visitors saw some of their strategies in action while touring orchards west of Rochester, where the land is flat and dotted with corn fields and woodlots. Most of the orchards are within a few miles of Lake Ontario’s southern shore. The big lake offers the orchards some protection from temperature extremes (even though temperatures dipped pretty low during the tour, as you can see from the photos).

Orchard Dale Fruit

At Orchard Dale Fruit Co., grower Robert Brown III showed IFTA rows of Honeycrisp trees on B.9 (about 1,980 trees per acre) planted in 2018, and rows of G.11 trees grafted from Smitten to Honeycrisp in 2021 (about 1,600 trees per acre). The trees were topped by bundled, single-row shade nets that are unfurled during the growing season to protect against sun and hail. The G.11s are “finally calming down,” he said, and he’s hoping for a “spectacular” crop in 2025. His target yield is 80 to 100 apples per tree, or about 75 (800-pound) bins per acre.

Brown frequently collaborates with Cornell Cooperative Extension researchers, one of the reasons IFTA recognized him as its 2025 Outstanding Grower during the conference. An ongoing trial is studying variable-rate sprayers for pesticide and thinning applications. He also uses variable-rate fertilizer spreaders to make up for the region’s uneven soil fertility.

Brown starts his Honeycrisp crop load management with blossom thinning in spring, when he’s “spraying pretty much nonstop for 48 hours,” he said. The pollen tube growth model helps him time his chemical bloom thinning applications, he said.

Brown uses labor software to keep track of worker activities, but other than that, he doesn’t rely very much on technology.

“It’s about the basics,” Brown said. “Good science and good math go a long way.”

Zingler Farms

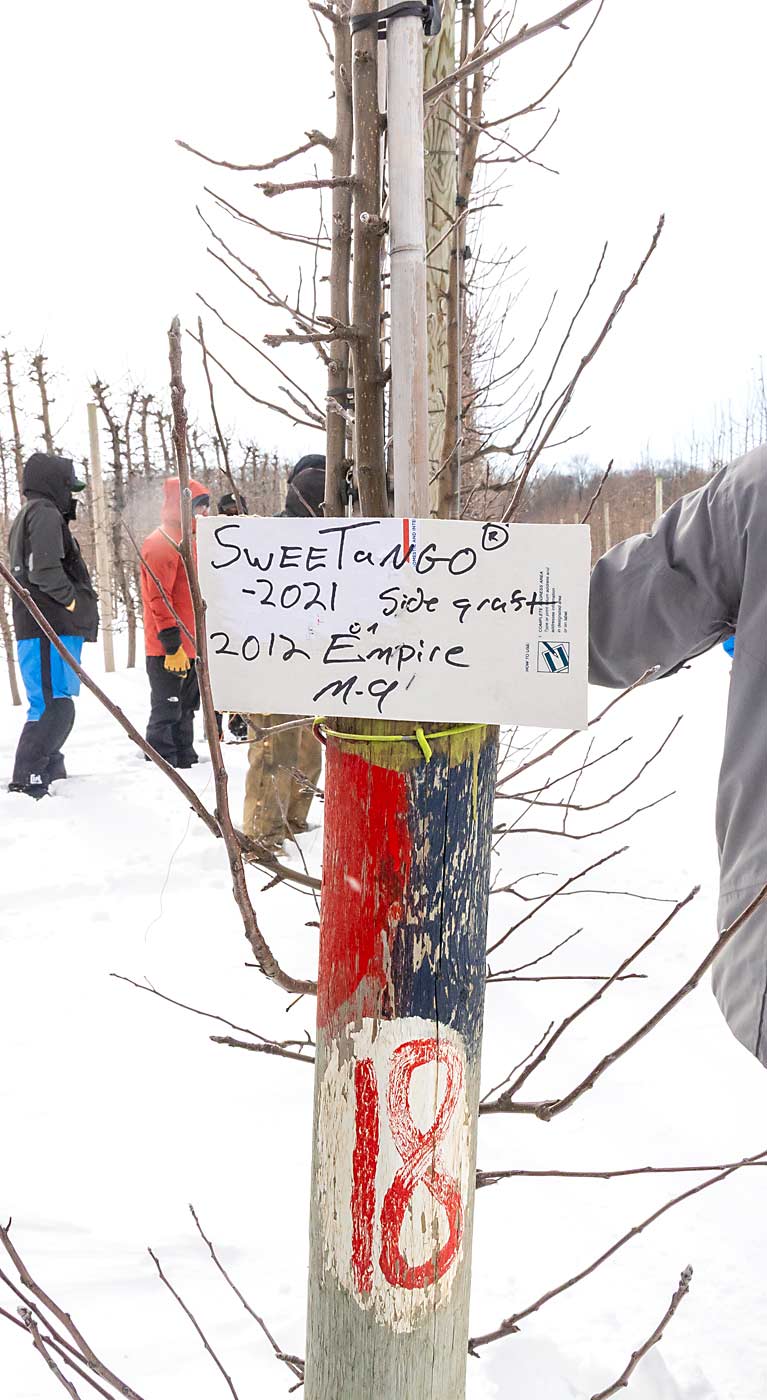

Mike Zingler and his son, Jimmy, showed IFTA a 2D Minneiska (marketed as SweeTango) planting on M.9-337 and G.41, spaced 2.66 by 9 feet. The rootstocks’ vigor is basically the same, but M.9 is a little more susceptible to fire blight, Mike said.

The narrow 2D system is “capital intensive,” with a lot of upfront costs, Mike said. It requires a lot of limb tying and structural training. Once the trees are tall enough and the canopies fill in, however, the system is relatively easy to manage. It’s reduced their Minneiska picks from three to five to just two. And the system’s uniformity allows for simple instructions for their employees.

“You can explain to your crew exactly what to do, and every tree will look the same when it’s all done,” Mike said.

Minneiska is a “nice apple to grow,” but requires “aggressive leaf pruning,” he said. Leaf defoliation machines give thin-skinned Minneiska microabrasions that show up later, so they use scissors to prune leaves that shade the fruit. For that labor-intensive task, they need a well-trained crew that won’t puncture the apples, he said.

They have lofty goals for the Minneiska planting — packouts above 93 percent and yields pushing 2,000 bushels per acre (or about 100 bins per acre) — but haven’t yet hit those numbers, Mike said.

Jimmy said they want four to five apples on each limb, or 80 to 100 apples per tree. They prefer simple instructions, such as “prune to the length of your hand,” to encourage orchard uniformity through the first five years, he said.

But that simple approach is not sufficient once the trees reach full production and fruiting site locations and bud counts become more significant, Jimmy said.

“We don’t want vertical dards coming off the arms,” he said. “We want horizontal fruiting units that carry our goal bud counts.”

Two of Clubs

At Two of Clubs Orchard, if a variety isn’t selling the way they’d hoped, growers Jill MacKenzie and Mark Russell don’t “sit around and go ‘boo-hoo,’” Russell told the IFTA visitors. They remove it.

McIntosh, Empire, Cortland, Red Delicious, Jonagold and Crispin? “Gone, gone, gone, gone, gone, gone,” Russell said. They’ve spent the past two decades cutting down freestanding trees and replacing them with tall-spindle Gala, Honeycrisp and Fuji, as well as managed varieties Minneiska, MN55 (marketed as Rave), NY 1 (marketed as SnapDragon), Cripps Pink (marketed as Pink Lady) and Regal 10-45 (marketed as WildTwist).

If a promising new variety doesn’t work out, they’ll remove that one, too. They showed the tour fourth-leaf Ambrosia trees they planned to graft over this year (“variety to be determined, but something fun,” Russell said).

He described their orchard as an “M.9-style” operation. About half their trees are on M.9 or its clones, about a quarter on Budagovsky 9, the rest on various Geneva rootstocks, all selected for consistent size. Early high-density plantings were 3 by 12 feet, but that turned out to be too wide for the “picker-friendly” system they’ve developed, he said.

MacKenzie said they followed the “New York tall-spindle recipe” for their early high-density plantings: tie branches down to induce fruitfulness and reduce vigor; remove two or three large branches every year and tidy up the rest. Once the trees started fruiting in years three and four, however, it became clear that recipe wasn’t quite right for their farm. The resulting trees were “kind of Christmas-tree shaped,” with long branches bending down and shading the branches below, she said.

“We were growing well-colored, good quality fruit on the last 18 inches of the branch, but we also had a real shade factory,” she said.

They now spend a lot of effort training, pruning, hedging and trimming their trees to create space.

“We talk about a fruiting wall,” MacKenzie said as her husband held up a piece of picket fence as a visual aid. “I don’t want a wall. I want a fence. You really need space between the trees.”

Despite advice to the contrary, she likes heading cuts. The stiff branches leave plenty of space for sunlight and air.

“Your best fungicide is air,” she said.

The fresh market demands that growers continually refine fruit count, quality and color if they want to sell apples. That’s why, at Two of Clubs, they manipulate their trees to make the apples as red as possible. There’s no money for them in the processing market, where apples don’t need to look quite as good, MacKenzie said.

“If you can get your apples redder, get them redder,” she told the IFTA visitors. “We have no use for undercolored fruit. Zero. None.” •

Leave A Comment