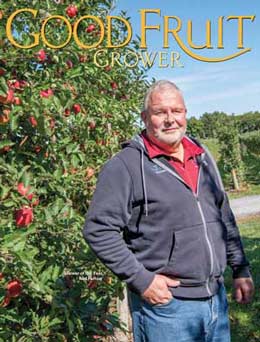

In an industry dominated by multigeneration family farms, Rod Farrow charted his own path — twice — as he bought into ownership of Lamont Fruit Farm and, later, when he engineered his retirement. He credits extensive planning and the model set by his mentor, George Lamont, with making those transitions successful, and he hopes it can serve as a model for other growers without a clear successor.

His ownership started with a disaster: the Labor Day storm in 1998 that blew the apples off the trees in every Lamont Fruit Farm orchard.

“We’d been suffering through the ’90s, like all growers had been, and the farm was put in a really bad place,” Farrow recalled. Financing for operations was uncertain unless Farrow, who had accumulated some profit sharing, took the risk to buy in at 33 percent ownership with brothers George and Roger Lamont. The Lamonts, who didn’t have children interested in taking over their fifth-generation family farm, promised him majority ownership in a few years.

George Lamont first saw the potential in Farrow when the younger man came to New York from his home in England, at 20, to live with Lamont and learn about fruit production. Several years later, in 1986, Farrow made the move to New York to work for Lamont full time.

“Most apple growers will hire people but never expect to bring them into the business. George saw this potential in Rod and offered to make him a partner,” said Terence Robinson of Cornell University, reflecting on Lamont’s unusual approach and how it paid off.

After years of running the 500-acre farm, Farrow took full ownership in 2009. And only a year later, he began planning his own exit.

“George always told me: ‘You need to know who your successor is by the time you are 50,’” Farrow said. “It’s always been important to me that the business outlives us. You have to hire the best people available because there’s 150 or 200 people whose families depend on this business.”

Farrow’s children, Rebekah and Sebastian, weren’t interested, but he already knew, in part, who he wanted to take over the farm. He credits Jose Iniguez, then general manager, with empowering the staff and leading the farm into precision-driven profitability.

Iniguez, an immigrant from Mexico, first came to work for Lamont Fruit Farm when he was 19. Farrow saw his talent with people and attention to detail, and he quickly moved him up the ranks. At first, Iniguez recalls being hesitant about the promotions: “I didn’t have any school, but Rod said, ‘Neither did I.’” A few years later, Farrow promoted him again to general manager.

“Jose just kept rising to the top. His ability managing people was better than anyone else I ever had,” Farrow said.

But he also knew that Iniguez needed a partner to be successful, someone who could run the business side the way Farrow did. So, when Jason Woodworth, a local grower who, like Farrow, focused on precision horticulture, was looking for his next opportunity, Farrow felt like he’d found the perfect team. He was 51.

Within a year of Woodworth coming on board, the three men spent much of the winter planning out how to share the responsibilities of farm operations and how the new partners would eventually buy Farrow out.

“It was very easy to have these conversations about our strengths and weaknesses because we are not family,” Woodworth said. “That was pretty dynamic to me to be sitting there in 2010 plotting our future. I don’t think 90 percent of family farms do that, because with family, it gets too personal.”

Just three years later, Iniguez and Woodworth were co-owners and Farrow started making a dedicated effort to get out of their way.

“You have to give them the job as fast as they can take it,” he said. “If I hadn’t seen it from George, I’m not sure I would have known quite how to do it. Someone else getting out of the way is really important.”

Like Lamont did years before, working with the New York State Horticultural Society and Premier Apple Cooperative in his retirement, Farrow took on new projects to keep himself busy off the farm.

“The only thing left for me to do (on the farm) was slap people on the back and tell them they are doing a great job,” he said. So, he took a leadership role with the International Fruit Tree Association and traveled the apple-growing world to make connections and discover new varieties. “I thought, the best thing I can do with the farm is get involved with every new variety that’s coming.”

For other growers thinking about succession, Farrow cautions that it takes more time than many expect.

“You have to find someone you want to work with, and they have to be able to succeed and pay you off at a fair market value,” he said. “I had to put things in place so that Jose and Jason could share in the profits from the operating company.”

The partners each bought 12.5 percent to start, Farrow said, taking out loans with the understanding that the farm would pay them enough in bonuses to cover it. Two more purchases later, and Farrow officially retired from the farm earlier this year.

Woodworth and Iniguez, now both in their later 40s, continue to work closely with Farrow in their orchard development partnership, Fish Creek Orchards. Woodworth said Farrow continues discussions about how things are going at Lamont, but he stays out of decision making. “With a mind like his, he’ll always have observations,” Woodworth said.

Iniguez said he’s now trying to follow Farrow’s example to make space for the farm’s next generation of managers and give himself more space to consider the farm’s future.

“I think I’m the first Mexican-born farmer at this level in New York, so I’m trying to be an example,” he said. “I’ve been doing this for 25 years, so it’s hard to stay away and let them do their jobs. It’s a learning process that has to happen. You cannot empower people without letting go.”

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment