Lamont Fruit Farm in Waterport, New York, installed drip line irrigation in some new plantings as a drought precaution as seen in June last year. Irrigation is becoming more of a necessity in the Northeastern United States, a fruit growing area that once relied solely on rainfall. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

Orchardists scrambled to find equipment. Growers used tanks and hoses to water trees by hand. And if you believe all the stories, desperate farmers tapped fire hydrants.

Those in New York who were still on the fence about the need for irrigation before the 2016 drought probably are convinced now.

“Always takes a slap in the face to make you move forward a little quicker,” said Todd Furber, owner of Cherry Lawn Fruit Farms, with 325 acres of tree fruit near the shores of Lake Ontario midway between Rochester and Syracuse.

The record-breaking 2016 drought drew headlines for its severity.

Growers who lacked irrigation improvised moveable systems using municipal water, while others watered by tank and hose, wrote Mario Miranda Sazo, a Cornell Cooperative Extension educator in Newark, and Lailiang Cheng, a Cornell University horticulturalist in Ithaca, in a “lessons learned” document. The federal government declared 24 upstate counties as natural disaster areas.

Fruit tree growers across New York without irrigation reported an average 46-percent crop loss in a January farm survey by Cornell, while even growers with irrigation saw 6 percent losses.

Unusual, but not unheard of

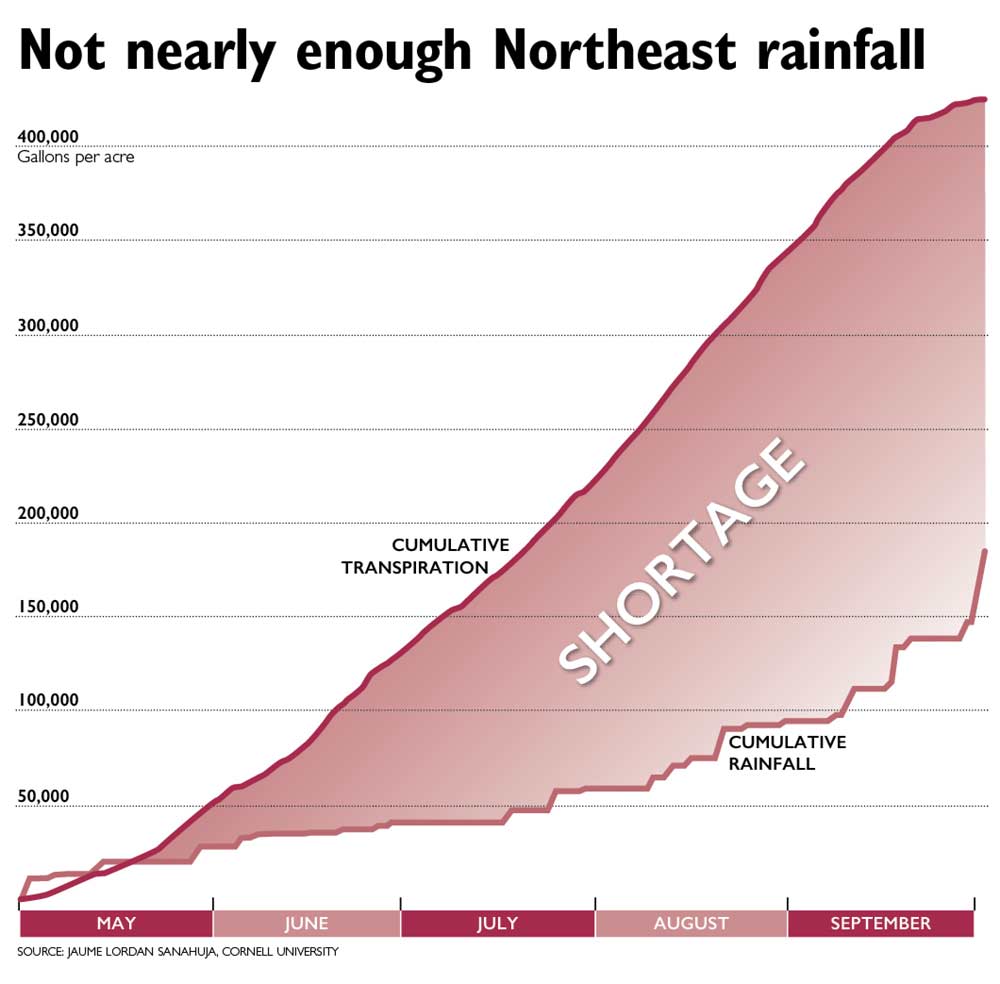

This graph tracks transpiration, the amount of water a tree used, compared to rainfall, the amount of water fruit trees received without irrigation, during the 2016 growing season. Obviously, rain was not enough, prompting growers to turn to irrigation in an area once believed to not need it. (Source: Jaume Lordan Sanahuja, Cornell University)

However, last summer was not the first water shortage in New York. Similar, if less severe, situations occurred in 2011 and 2012, while the two researchers estimated in their document that three of every 10 summers will see a water shortage.

Even in a normal year, they said, “rainfall is usually less than required for optimal tree performance during critical periods of tree establishment and growth.”

Growers always expect a few dry weeks each summer. Thus, upstate New York farmers have been steadily, if slowly, marching toward irrigation for several years. Waiting and hoping for rain is becoming an outdated model for growers, both in New York and in Pennsylvania, Michigan and other fruit producing areas.

“Our practice is to put in irrigation when we plant a new orchard,” said Tom De Marree of De Marree Fruit Farm, another Lake Ontario orchard between Rochester and Syracuse. Young trees are the most susceptible to drought stress.

De Marree estimates about 80 percent of his orchards have irrigation now, probably well ahead of the curve compared to his neighbors in the area. Others put their progress toward irrigation at about 30 percent but follow a similar routine, adding drip irrigation when they put in new trees. Few try to absorb the cost all at once.

De Marree became convinced more than 10 years ago when he ran an unofficial trial, leaving part of one apple block unirrigated due to inconvenience. The fruit there turned out small. “You could physically see the fruit size difference in the bin,” he said. The following spring, those same trees had less bloom and a reduced crop.

Irrigation picking up pace

Recent summers have sped up the rate of irrigation in the Northeast, said Liz Madison, manager of Belle Terre Irrigation and Packaging, a farm service supply business near Syracuse and Rochester with customers throughout the Northeast states.

“Due to the weather, over the last five years we have definitely seen an increase in the amount of new systems being put in,” Madison said. “Many large and growing farmers have decided to build irrigation costs right into the cost of putting in an acre of fruit.”

Of their 2,343 customers, 59 percent purchased irrigation between 2009 and 2013. From 2014 to 2017, that jumped to 65 percent.

Trends are similar in Michigan, Pennsylvania and Virginia. The importance of irrigation in Eastern states comes up frequently at conferences and workshops, but extension educators have to twist few arms anymore.

“It’s increasingly becoming less of an argument to convince growers of irrigation,” said Jim Schupp, professor of pomology at the Pennsylvania State University Fruit Research and Extension Center in Biglerville.

In the 1970s, when apple trees in the Mid-Atlantic had deep roots, long branches and more of their fruit destined for processing, a researcher determined that man-made supplemental irrigation paid off only once every 10 years, Schupp said. Today, with the increased emphasis on large, fresh fruit and high-density planting, “it’s become an essential matter.”

For the most part, growers believed that lesson before the 2016 drought, which was just as cruel to the apple growers of south-central Pennsylvania as it was to those of upstate New York. The region, centered around historic Gettysburg, had one “meaningful” rainfall between mid-June and mid-September, Schupp said. Grapes and peaches fared well, but “anybody that didn’t have irrigation on apples had their head handed to them.”

Syracuse receives an average of 43 inches of rain per year; Grand Rapids, Michigan, gets 37 inches; Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, 43 inches. Yakima, Washington, where no one dreams of growing fruit without irrigation, gets 8 inches.

Farmers come around

Not surprisingly, capital costs are the main cause of reluctance.

Costs vary, but in general, Northeast growers pay up to $760 per acre to install drip irrigation with a municipal water source, said Madison of Belle Terre. That goes up to $1,200 per acre if they need to install a well and electric pump.

Meanwhile, water itself is expensive in New York. Not all wells work out, growers said, so many tap into municipal county water systems, paying the same rates as residential users. In Wayne County, that’s at least $3.25 per 1,000 gallons and could go up this year, Miranda Sazo said.

After 2016, David Coene of Windmill Farms is starting to think that’s worth it. He has some drip irrigation, but has not systematically added it with new blocks, when higher densities and new varieties push the cost of a new orchard above $10,000 or even $20,000, he said.

“That trickle cost doesn’t look as daunting as it used to,” said Coene, who grows about 300 acres of fruit straddling the border of Wayne and Monroe counties.

Most growers have built drip irrigation systems that merely supplement rainfall and had trouble keeping up with last year’s drought. Coene laughed at the irony; the area is sometimes mocked for its lack of sunshine, and he can see the vast expanse of Lake Ontario from his house.

Mark Hermenet of Hermenet Fruit Farms, also in Williamson, estimates he spent about $900 per acre on plant growth regulators, trying to eke enough size out of his fruit in last year’s dent. Again, that made the cost of irrigation not seem so high, he said.

“Typically, we don’t need a whole lot of irrigation here,” he said.

Research

If the 2016 experience was not enough to convince growers of the need for irrigation, Cornell faculty made sure to tell them at the Empire State Producers conference in January in Syracuse, New York.

During his presentation, horticulturist Jaume Lordan Sanahuja displayed a graph that showed transpiration — how much water fruit trees used — in 2016 versus rainfall in Geneva, New York. The lines weren’t even close; transpiration was way, way above rainfall.

“So, when transpiration was far above rainfall, unless we irrigate, we will be in trouble, since trees will need more water than available,” Lordan Sanahuja said.

Lordan Sanahuja, relatively new to Cornell, was surprised to see so little irrigation in the area.

“When I first started working at Cornell, in 2015, I was surprised while setting irrigation trials that some growers were more afraid to irrigate too much rather than to not irrigate,” he said.

In the results of those trials, Lordan Sanahuja reported higher yields in irrigated compared to nonirrigated apple orchards in the Hudson Valley.

What’s more, he used apple prices to estimate that an irrigated orchard with 4,900 trees per hectare would bring in an extra $6,800 in revenue compared to the same density on a non-irrigated orchard. And that was in 2015, an ample water year.

In his Syracuse talk, he steered growers to a Cornell evapotranspiration model that helps them calculate how much water their trees need based on soil, rainfall and other factors.

“We’ve lived a very privileged life here with water,” said Coene of Windmill Farms. That life may be ending. •

What to do?

Here are a few tips about irrigation for growers in the Northeast from a Cornell University report in the wake of the 2016 drought.

—If at all economically possible, add irrigation to all new orchards to water young trees right away.

—In dry years, start using drip irrigation in early or mid-May. In wetter years, delay until early June.

—Fertigate for the first three years with small amounts of water and nutrients applied twice weekly. Use 5 gallons per tree per week in year one and 10 gallons per tree per week in year two.

—Improve soil structure with the addition of organic matter, such as compost or crop residues.

—Get to know your soil by taking samples at least every two to three years, more for sandy soils. Fall is the most reliable measurement time. Shoot for soil pH between 6 and 6.5.

—Use the evapotranspiration model to help you calculate how much water your trees need. To find it, visit newa.cornell.edu, then find and open Apple Irrigation under the Crop Management heading.

-by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment