Tired of hearing about little cherry disease?

Don’t worry. Ashley Thompson knows plenty of other diseases are out there trying to kill your trees, reduce your yield and ruin your day.

The Oregon State University tree fruit extension horticulturalist reports finding four viruses — tomato ringspot, cherry mottle leaf, Prunus necrotic ringspot and prune dwarf — in her region near The Dalles, though other Northwest growing areas probably have them, too, she said. All four of the viruses will reduce yields, but some also damage the fruit and end up fatal to trees.

Thompson arrived just a few years ago, so she and the growers she works with are not sure if the virus problems are surging or if growers are just more on the lookout for trouble now with the awareness of little cherry disease and X disease.

“The more they look at their trees, the more things they’re finding,” she said.

Either way, Thompson has been identifying and flagging infected trees, taking samples and sending them to a lab for genetic confirmation. In late May, she held a small tour for local growers, one of her first in-person gatherings in more than a year since the pandemic began.

All four of the viruses Thompson mentions have been around for decades, though tomato ringspot seems to be surging in the past few years, said Jay Pscheidt, an Oregon State University plant pathologist in Corvallis with 30 years of experience.

“The ebb and flow is on a decades scale,” he said.

However, new ones occasionally show up. For example, cherry leaf roll virus has a documented history in Washington but appeared to miss Oregon until about four years ago when a grower alerted the university to some unusual symptoms in a mature tree near a road. Pscheidt and colleagues used Google Street View archives to date the disease, or at least the symptoms. The orchard has since been removed and, so far, they haven’t found the virus again.

This doesn’t mean growers in The Dalles can forget about the headline-grabbing little cherry disease, an umbrella term used to describe the small fruit resulting from two distinct pathogens: little cherry viruses and the X phytoplasma. Combined, the Northwest Cherry Growers association estimated the disease will decrease production by up to 30,000 tons throughout the five states it represents. As far as Thompson and her colleagues can tell, the Columbia Gorge region along the border of Washington and Oregon does not have little cherry virus, but X disease is prevalent.

Whether it’s X disease or Thompson’s “other” viruses, area growers are removing trees or entire blocks, chalking it all up to the cost of doing cherry business.

“I don’t like it. I remove the tree,” said John Byers of Byers Orchards.

They even joke that all cherry trees just have a habit of dying from the day they go in the ground.

They also tease Thompson for giving them more to worry about, calling her a new doctor in town talking about a previously unknown shoulder problem.

“Suddenly, everybody’s arm is in a sling,” said Gary Wade, who also owns an orchard well-flagged by Thompson.

Tree removal is usually the recommended course, but Thompson is encouraging growers to contact her for scouting visits and genetic testing to diagnose the viruses. Not all of them require the same management program. For example, fumigation is not necessary for pollen-borne viruses such as Prunus necrotic ringspot but it will help weed out those that infect roots, such as tomato ringspot.

“That’s why you need to identify pathogens,” she said. She sends samples to the OSU Plant Clinic in Corvallis to confirm her findings.

Some growers replant the next year, right in the same hole from which they just removed a tree, because they can’t afford to wait for production to come back. Others spray broadleaf weeds that may provide a habitat for vectors — a practice that’s recommended by Washington State University entomologists for the leafhoppers that vector X disease. Another nearby grower plans to fallow a removed block with Sudan grass, a fast-growing forage known for replenishing organic matter in tapped-out soils and warding off nematodes. Wade has used a backhoe to rip out roots, grind up the cuttings and use them as mulch where he couldn’t fumigate.

“It’s so critical to get all the roots out,” Wade said.

Wade, who owns an orchard with his wife, Marlis Rufener, recently removed 84 trees from one 10-acre block because of X disease. In a block of Chelans, he will continue to remove individual trees and, most likely, will eventually take out the rest of the block due to tomato ringspot and some of the other soilborne viruses Thompson has been noticing.

In mid-June, Thompson, Wade, his son, Devin, and Alan Reitz, a field representative for Mount Adams Fruit, walked through the block. The cherries themselves looked good, but many trees had large sections of blind wood with rosetting leaves growing small and in tightly packed clusters, a sign of tomato ringspot. The branches also had dead, dried up, small leaves amid the clusters. They also found enations: darkened, scaly growths along the midrib of leaves. They indicate several of the culprit viruses and help differentiate from bacterial canker.

Reitz, who has 22 years of cherry field work under his belt, calls the viruses a background problem. He’s unsure if they are increasing or just getting more attention.

“I just know that it’s out there and people have lived with it,” Reitz said.

—by Ross Courtney

On the lookout

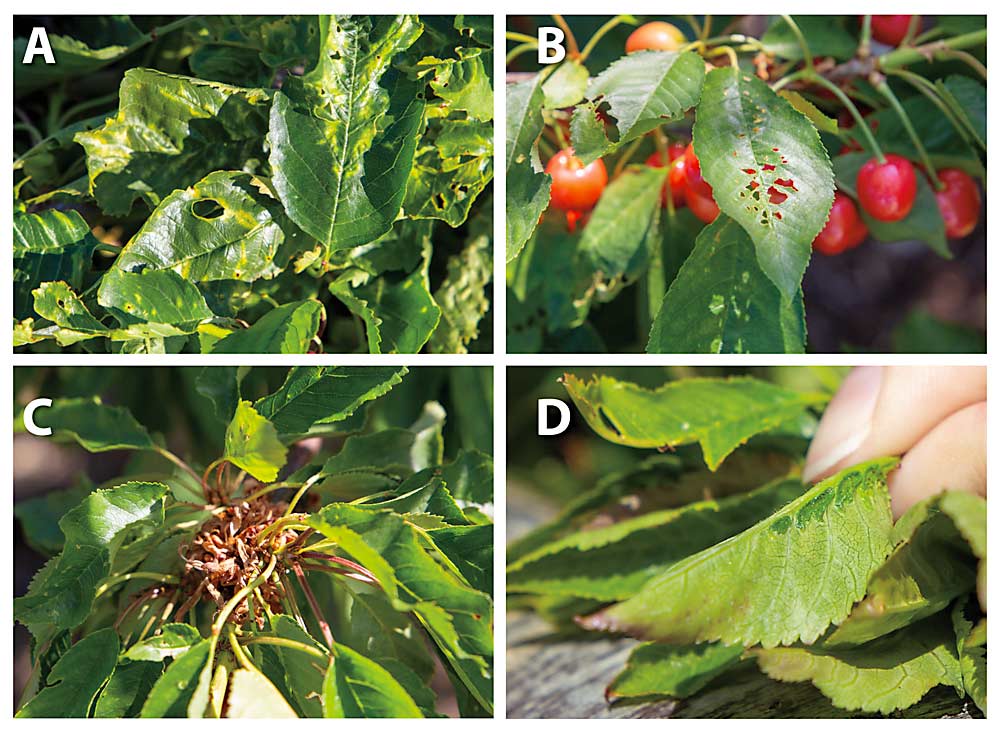

Ashley Thompson, Oregon State University tree fruit extension horticulturist, has been spotting signs of a variety of cherry pathogens. Besides X disease, these are four of the most common in her area near The Dalles in the Columbia Gorge, with their symptoms taken from Thompson, the Pacific Northwest Pest Management Handbooks, available online at pnwhandbooks.org, and the University of California’s IPM guide, online at ipm.ucanr.edu.

—Tomato ringspot virus causes sections of blind wood, low yield and poor fruit set. Look for enations on leaves near the trunk. Enations are dark, scaly growths along the midrib and leaf veins on the back of leaves. Root-feeding nematodes are the vector. Mazzard rootstocks are susceptible. It’s not typically fatal to trees.

—Cherry mottle leaf virus causes mottled patterns on leaves, often with yellow hues, that sometimes develop into shot holes. It also causes rosetting, small leaves growing in tight clusters. Transmitted by mites, it’s sometimes mistaken for herbicide damage. It reduces fruit size and flavor and can cause fruit to ripen later, but it is generally not fatal to trees.

—Prune dwarf virus causes yellow patterns on leaves, blind wood, narrow and long leaves and reduced yields. It is pollen-borne, so soil fumigation won’t do any good. Certain strains of the virus can be fatal to trees planted on Krymsk rootstocks.

—Prunus necrotic ringspot virus causes yellow rings that sometimes develop into shot holes, can reduce yields up to 15 percent and delay ripening. It is also pollen-borne; soil fumigation won’t help. Certain strains of the virus can be fatal to trees planted on Krymsk rootstocks.

Thompson is asking growers who spot suspected symptoms of the four viruses to contact her for sampling and genetic testing. Email her at ashley.thompson@oregonstate.edu.

—R. Courtney

Leave A Comment