In early January, a 26,000-square-foot warehouse at Willow Drive Nursery stood vacant. The only things it held were unused racks and pallets, moved inside to protect them from the weather.

“Normally this would be stuffed,” said Jim Adams, co-owner of Willow Drive, a nursery and rootstock company near Ephrata, Washington.

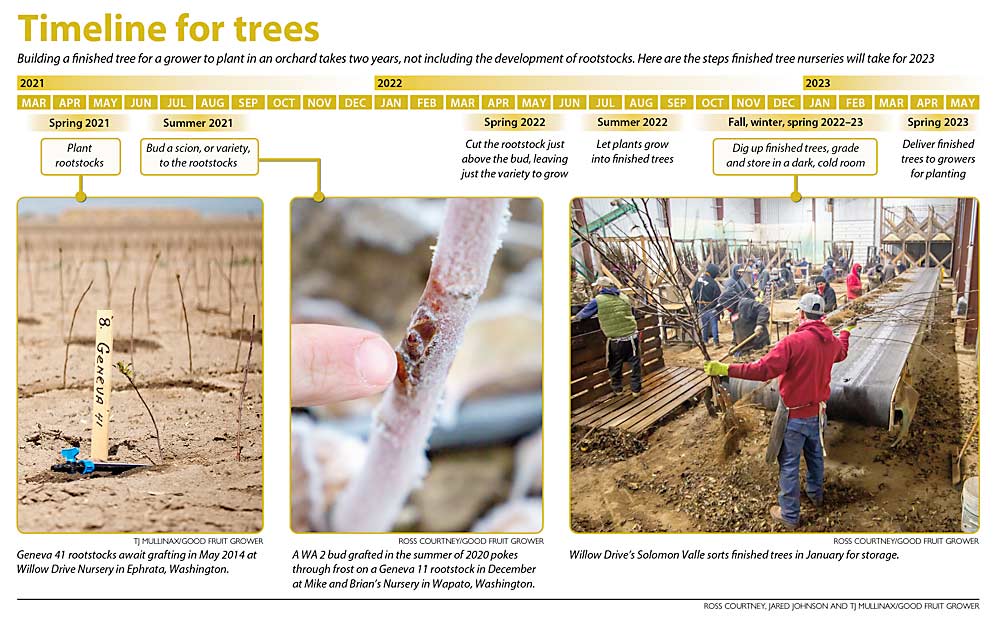

Like many of the apple growers it supplies, Willow Drive just hasn’t been planting as many trees. This year, the company is planting roughly half the rootstocks it did just two years ago.

As the U.S. apple industry slowed planting in the face of declining prices, nurseries have felt the pinch. They have responded with a contraction in supply, which makes it even more important for growers who want to buy trees to plan ahead and seek contracts, nursery owners say.

Until the past year or two, the contract market for nurseries was booming, as consolidation of production companies, sometimes with a rush of investment money, led to bigger orders and more concrete long-term plans. Waiting lists for new Geneva rootstocks pushed the horizon out ever further. Some nursery managers have orders for 2025 on their desks.

Then the lull happened and flipped the script. This spring, nurseries are planting a larger share of their 2023 inventory on speculation, trying to guess what growers will want after the two-year tree-making process.

Supply and demand

Nurseries have always planted some trees on spec and sometimes end up with more trees than they can sell. It’s a calculated risk.

Ramiro Avilez, a sales agent and field representative for Van Well Nursery in East Wenatchee, Washington, estimates Van Well’s apple trees are roughly half contract, half spec.“We try to have trees for growers who make a decision last-minute,” he said.

Cameron Nursery in Eltopia, Washington, started 2021 with extra finished EverCrisp trees, hoping for a last-minute spot-market buyer — or they’re destined for the burn pile.

“It’s not like a hardware store where we can keep shovels until it snows,” said owner Todd Cameron.

The managed, open variety had been selling hot until the coronavirus prompted stores to stick with more tried-and-true varieties. That shift in demand has already worked its way back to the nurseries.

This year, Cameron and his family plan to cut back their acreage by roughly one-third compared to the average of the previous three years. A few years ago, they grew virtually all their trees for contract because growers knew what they wanted. Now, about 90 percent of the new trees will be destined for the 2023 spec market, he said. They’re just guessing at what growers will want by then.

“We don’t go to Vegas to gamble,” said Allison Schrader, business manager for Cameron Nursery and Todd Cameron’s daughter.

Won’t last long

Nurseries don’t expect this moment of uncertainty to last long. When the apple industry finds its footing and growers pick up the pace of planting again, nursery executives warn that growers won’t necessarily get the varieties they want without prior planning.

“We’re not a drive-through Wendy’s,” said Gary Snyder of C&O Nursery in Wenatchee.

In 1991, when Snyder first came back to his family’s nursery business, only about 20 percent of the industry worked on contract. Each winter, growers could pretty much count on being able to buy whatever they wanted. Many made their down payments at the winter horticultural shows.

The ratio has flipped since then, Snyder said. At least 80 percent of his nursery business is contracted two, three or even five years ahead.

Many nurseries are hesitant to start the two-year tree-building process unless they know they have a buyer. Widening rootstock selection and proprietary varieties compound the squeeze.

“Quite frankly, I’ve never felt like my crystal ball has been more cracked,” said Dale Goldy of Gold Crown Nursery in Quincy, Washington.

Goldy said he received several calls over the winter from legacy growers not involved with a proprietary variety. They ask for tens of thousands of trees based on available inventory, not on a long-range planting formula. WA 38 is a common choice, but they ask for other varieties, too. They also mix and match rootstocks.

Many of them simply don’t know what they want to plant, he said.

Eastern U.S. and rootstocks

This crunch has not hit Adams County Nursery as hard, said Phil Baugher, president and co-owner.

The Aspers, Pennsylvania, nursery supplies some commercial producers on contract, but the company mostly serves small-acreage, direct-market growers from Maine to Georgia with a product line of 80 varieties of apples, not to mention 100 different peaches. Average commercial orders are around 1,000 trees with multiple varieties, compared to orders in the hundreds of thousands for a single cultivar, common in the Northwest.

Still, the company began noticing the contraction in apple contracts, starting about June last year, as commercial growers ordered fewer trees for delivery in 2022. This year, Baugher and his family will have fewer employees and fewer trees in the ground for the first time in roughly a decade.

“We were riding the crest for eight to 10 years,” Baugher said. “Basically, whatever we could grow, we could sell.”

Baugher, a fourth-generation nursery owner, has seen apple industry cycles come and go. He figures this one will last two or three years, like the others, but he hopes it all turns around before rootstock nurseries need to cut back on their stool beds, which can take four or five years to re-establish.

It’s a valid concern, said Brent Smith, vice president of Treco, a Woodburn, Oregon, rootstock and tree nursery. Even large growers still occasionally try to change their minds overnight from 500,000 M.9 roots to 500,000 G.41 roots, for example, and get frustrated when the answer is no.

“Theydon’t understand the process,” Smith said. Rootstocks take a few years to develop, and producers can’t pivot quickly.

The current economic lull doesn’t change that. True, after years of waiting lists, companies such as Treco actually have rootstock inventory available for spot purchase this year. Unlike finished trees, stool beds produce the same number of plants whether they are sold or not.

But the rootstock nurseries won’t do that forever, Smith said. If the economy doesn’t turn around and start using up the inventory, they’ll have to dig up some of the beds. “It won’t be there when things swing back around,” he said.

Nursery industry leaders who spoke to Good Fruit Grower remain optimistic about the long-term outlook.

Willow Drive of Ephrata, which produces finished trees and rootstocks, has already revamped rootstock stool beds, replacing 1.5 million Budagovsky 9 and Malling 9 clones with Geneva roots over the past five years.

The company just built a new rootstock building, quadrupling its rootstock capacity. The pandemic has pushed interest rates so low, and the company needed the upgrade, so the Adams family pulled the trigger now.

Adams sees it as critical for the company’s next 50 years in business.

“With the things we got in the works, we’ll be going for a long time,” he said. •

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment