History and geography have dealt Washington’s northernmost growing area some unlucky cards in today’s apple game.

Consolidation has left few packing choices in the Okanogan River Valley, rocky soils make breaking ground arduous, and mountainous terrain pinches growers who want to expand. Grower Dave Taber, considered a large grower for that area, farms 300 acres scattered among 14 different locations.

“It’s nuts,” Taber said.

However, independent growers in the region have a few aces up their sleeves. The microclimate is conducive for club varieties with Honeycrisp parentage, while relationships to larger companies have provided access to those varieties and, in several ways, buoyed the region.

“We think we have, maybe for the first time in our life, a real geographic advantage,” said Allen Godwin, who manages a family farm with his brother, Sam Godwin, in Tonasket.

The region’s hills temper afternoon highs, giving nighttime cooling a head start and fewer days of extreme heat. Cherries, pears and apples, especially sun-sensitive Honeycrisp spinoffs, thrive in those conditions.

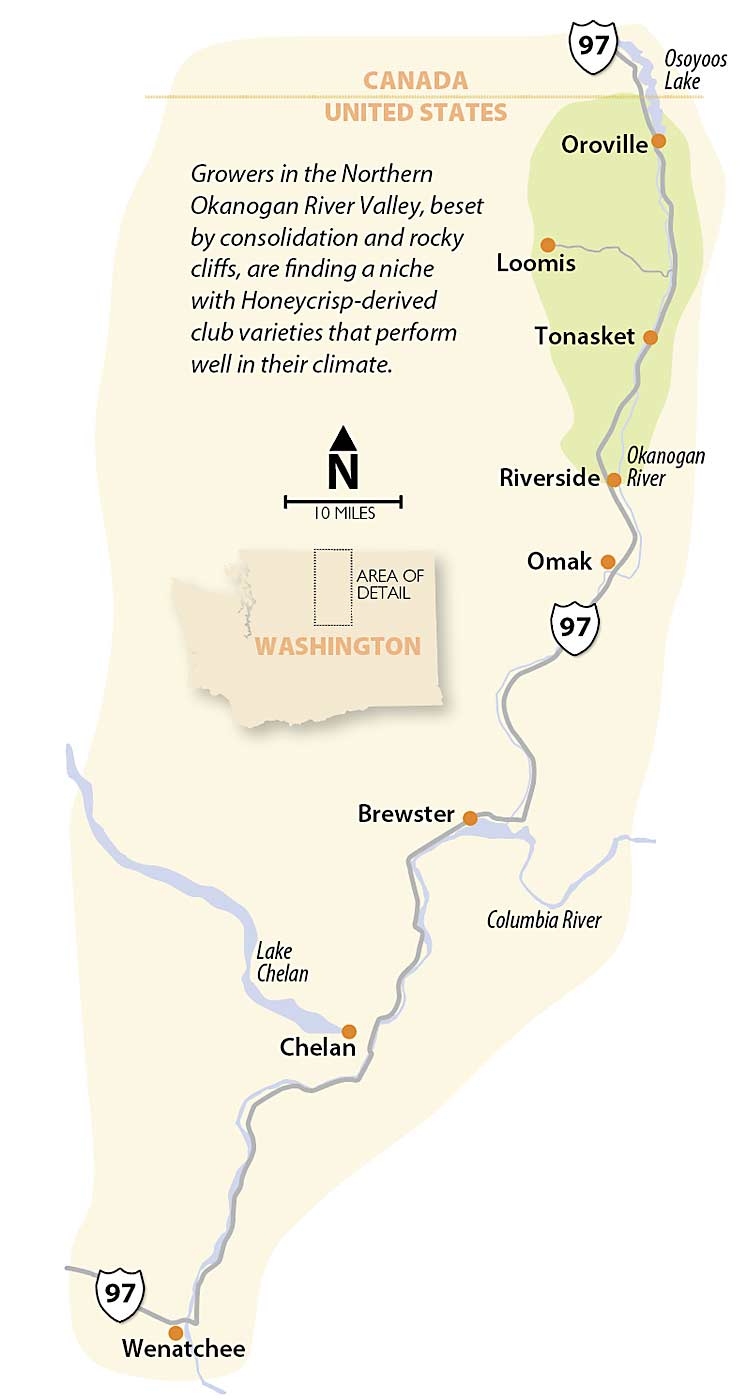

Not that it’s exactly cold in the narrow northern reaches of the Okanogan River Valley, which stretches 38 miles south from the Canadian border to the community of Riverside, just north of Omak, where the valley begins to widen. Daytime highs in July and August over the past 10 years in Oroville, just a few miles south of the U.S.-Canada border, averaged 88.4 degrees and 87.4 degrees, respectively — within 2 or 3 degrees of Mattawa, Wenatchee, Pasco and other locales hundreds of miles to the south, according to historical data on Washington State University’s AgWeatherNet.

However, extreme heat is lower, according to the network. The Oroville station recorded 43 days of 100 degrees or hotter in the past 10 years, much fewer than those other communities. The region’s longest stretch of consecutive days over 90 degrees was 13 days, a relatively short stretch compared to the southern growing regions of the state.

SugarBee and others

Those temperature dynamics make the area ideal for SugarBee, a blush Honeycrisp offspring gaining commercial momentum, said Harold Schell, variety development director for Chelan Fruit, one of three packing companies who work with growers in the Okanogan River Valley.

SugarBee, a Regal Fruit International product from an open-pollinated Honeycrisp in Minnesota, grows throughout Washington in latitudes both north and south, but southern growers require more overhead cooling or shade cloth, Schell said.

Chelan Fruit, a cooperative in Chelan, and Gebbers Farms, a large private company based in Brewster, share the rights. The two collectively packed about 8,000 bins in 2019 and 27,000 in 2020, Schell said. This year, they will reach roughly 50,000.

The companies see SugarBee as a trade-up for Red Delicious; they have similar harvest timings. Top grades of the club apple go for $65 per box, said Schell.

To keep those prices high, each of the two license holders has capped plantings at 1,500 acres, Schell said. Growers began planting in Washington in 2014 and will reach those caps within a year or two, he said.

The two companies also have North American rights to Dazzle, a New Zealand apple, while Chelan Fresh, a marketing partnership between Gebbers and Chelan Fruit, is experimenting with Lucy Rose and Lucy Glo, two red-fleshed dessert apples. Honeybear Growers, a Brewster company that works with 35 growers in northern Washington, has Pazazz. And, of course, some growers are banking on the WA 38, marketed as Cosmic Crisp, a managed variety open to all Washington growers.

All of those varieties have Honeycrisp in their lineage, where cooler weather helps with quality.

“My perspective is, we have a slight advantage because we are a bit cooler,” said Jim Divis, general manager of Honeybear.

New varieties are a risky gamble in the crowded fruit market, Divis said. Pazazz, first planted at commercial scale five years ago, makes up about 10 percent of the company’s manifest, while Honeycrisp proper is roughly 60 percent, Divis said, compared to the 11 percent in the state overall.

The microclimate is good for cherries, too, said Cass Gebbers, CEO of Gebbers Farms. The region, which Gebbers calls “the North District,” grows Lapins, Skeena and other varieties developed at the research station in Summerland, British Columbia, about 50 miles north in Canada’s Okanagan Valley, part of the same geological formation with similar growing conditions but a different spelling.

Elevated and ridge-lined growing sites, such as those in the North District, accentuate differences between daytime highs and nighttime lows, helping fruit develop acid and robust cellular structure that holds up better in storage and shipping, Gebbers said. Also, the mountains protect fruit trees from damaging wind, he said.

History and future

If the gamble on Honeycrisp-derived varieties pays off, few regions need the good luck more than the Okanogan River Valley. Consolidation has hit hard in the area, once home to dozens of independent fruit packing warehouses. In 1974, cooperatives Omak Fruit Growers and Brewster Mutual Growers Association merged to become Mutual Apple Growers Inc., or MAGI. MAGI merged with more companies throughout the 1980s and 1990s, then combined with Trout-Blue Chelan in 2004 to form Chelan Fruit, based more than two hours south of Oroville.

The last local North Central Washington facility closed in 2016, when Oroville’s Gold Digger Apples, a cooperative named for the area’s mining roots, went bankrupt. Chelan Fruit, already well positioned in the north from previous mergers, absorbed most of Gold Digger’s 40 or so growers and purchased one of the company’s Oroville buildings to use as a receiving warehouse.

Gebbers bought the remainder of the facilities, including Oroville apple and cherry packing lines, which they use for their own fruit, preserving hundreds of local jobs. The company has also replanted most of the orchards purchased from Gold Digger’s bankruptcy sale to new, proprietary varieties with modern tree structures. Local growers have been diligent about doing the same, Gebbers said.

“The apple deal has been a tough row to hoe for several years, and there has been some shakeout,” Gebbers said. “However, the result is, the very best growing sites are still here and producing.”

Gebbers, one of the largest production companies in the state, brings corporate scale to the area, but the makeup of the region is mostly smaller family farms, such as the Tabers’, the Godwins’ and the farm of Richard and Jill Werner.

Jill, who has an agricultural economics degree from Washington State University, grew up with five or six packing houses in Oroville alone and recalls the days of her father and his friends sitting on the hoods of their trucks waiting for their turn to unload. But she wastes no time on nostalgia. The small companies of yesteryear had to merge to gain any leverage in the global marketplace.

“I’m enough of a realist, I don’t spend a lot of time pining for it,” she said.

Even Richard, known for conservative horticultural decisions, agrees the club varieties are the way forward.

“I know I said I don’t support club varieties, but I have had to reinvent myself,” he said with a laugh.

The card game has simply changed in the area, and the players continue to adjust.

“A lot has changed and there’s more change to come,” said Taber, a Chelan Fruit board member.

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment