Ron Moorse, a foreman with the Bureau of Reclamation, shuts the Roza Irrigation District down the morning of May 11, 2015, in Yakima, Washington. The canal returned to service growers on June 1. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

Research associate with Washington State University, Prosser.

The Roza Irrigation District, which delivers water to cropland in Yakima and Benton counties, shut down its water for nearly three weeks in May and plans to end the irrigation season on September 30.

The decision to reduce water flow to junior water rights users resulted from the lack of snowpack in the Cascade Mountains and low water levels in reservoirs. Snow melt goes into the Yakima River, and water is then routed to multiple irrigation districts in eastern Washington.

The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation forecast for Roza water users is only 44 percent of the usual water delivery for the 2015 season. Sunnyside Valley Irrigation District, which serves primarily senior water rights users along with other junior users in the same region, is also rationing water by reducing flow rate down to 5.7 gallons per minute per acre. Other irrigation districts in the Yakima River Basin are also restricting water delivery for this season.

Effect on crops

Dr. Troy Peters, Washington State University’s Extension irrigation specialist based at the Prosser Irrigated Agriculture Research and Extension Center, explains that while plants need water throughout the growing season, they can recover more easily from the stress of lack of water when they are in a vegetative stage or at least in early season. In the past drought years (1994, 2001, 2005) when the Roza District restricted water flow, it shut the water off in April or May.

Many crops, including grapes, are typically pre-bloom by the end of May. However, fruit trees are producing fruit and some varieties of cherries are close to harvest by then. Moreover, harvest of many cherry orchards is occurring earlier this year because of warmer than average springtime temperatures. Yields of some cherry blocks in the Roza District may be impacted by the lack of irrigation just before harvest.

In a recent presentation to growers, Peters explained how a crop responds to soil water deficits through yield response and stated that crops could withstand a 20 to 30 percent loss of water delivery with only moderate reductions in yield, but water shortages greater than 40 to 50 percent would likely result in more extreme yield losses.

During this season, growers can apply for permits to use emergency well water from the Washington State Department of Ecology. Depending on the irrigation district, growers may also lease or buy irrigation rights from landowners not using the land.

Most climate-change models predict minimal future changes in precipitation amounts for the Pacific Northwest. However, the predicted increased temperatures will lead to earlier spring runoff and greater summer crop water demands, creating a greater gap between water supply and demand during the hottest part of the summer.

Hence, these models predict that additional water storage in reservoirs or in the groundwater will be required in the future to maintain current levels of crop production.

Irrigation Scheduler

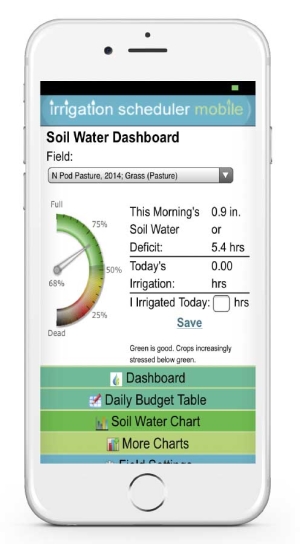

Figure 1. Mobile view of the Irrigation Scheduler site. (Courtesy AgWeatherNet)

Peters, who is also an engineer, has worked with Gerrit Hoogenboom, Sean Hill, and Cynthia Tiwana of WSU’s AgWeatherNet program to develop a simplified Irrigation Scheduler for all growers in Washington State.

This Web-based program, which works on desktop computers and mobile devices, is based on a soil water budget model that considers water uptake by plants, existing water in soil, irrigation and rain inputs, and loss of water from plants to the atmosphere (evapotranspiration).

Peters summarizes this model as “tracking water in and water out.” In addition, Peters said that applying more water than the soil can hold results in water loss via deep percolation. He says that the more obvious water loss from surface runoff is typically small compared with water losses to deep percolation.

Users of Irrigation Scheduler may log in through the AgWeatherNet site (weather.wsu.edu/ism/) and start using the system by entering information about their orchard or vineyard block. A grower chooses name of field, crop, closest weather station, and soil texture (silt, loam, sand, etc.).

The dashboard view shows an easy-to-read soil water gauge with a needle that goes from “Full” (100 percent) to “Dead” (0 percent) (see Figure 1). Growers may also interact with the program and change data or estimated numbers used in the model to figures more appropriate to their operations.

Information returned includes the amount of irrigation needed to replenish the soil profile on a given date as well as the irrigation history of that particular block. A seven-day advance forecast of water needed is available too. Growers may opt to receive “push” notifications on irrigation needs through email or text messaging.

Since this Irrigation Scheduler was released in 2013, hundreds of growers have been using it. The program is available in ten western states and Alberta, Canada; it can access data from nine agricultural weather networks. Peters plans to expand to Midwestern states this year. Contact Troy Peters at troy_peters@wsu.edu for more information.

Leave A Comment