Growers in Washington, or anyone looking to develop property that was once an orchard, should not be surprised if they face questions about farming methods abandoned generations ago.

State environmental officials, developers and municipal planners have begun drafting methods to consistently manage the challenges of building on property that may be contaminated with legacy soil pollutants from orchard practices dating back more than a century. The state Department of Ecology created a working group of developers and planners who want to streamline and standardize the way they screen property throughout Central Washington for legacy lead and arsenic contamination.

The outreach by the department is mostly for property owners and developers. But growers, especially those with historic orchard property, should be aware of the effort, too.

“It’s good for the growers to be knowledgeable about what Ecology wants to do,” said Valerie Bound, section manager of the toxics cleanup program at the department’s central regional office in Yakima.

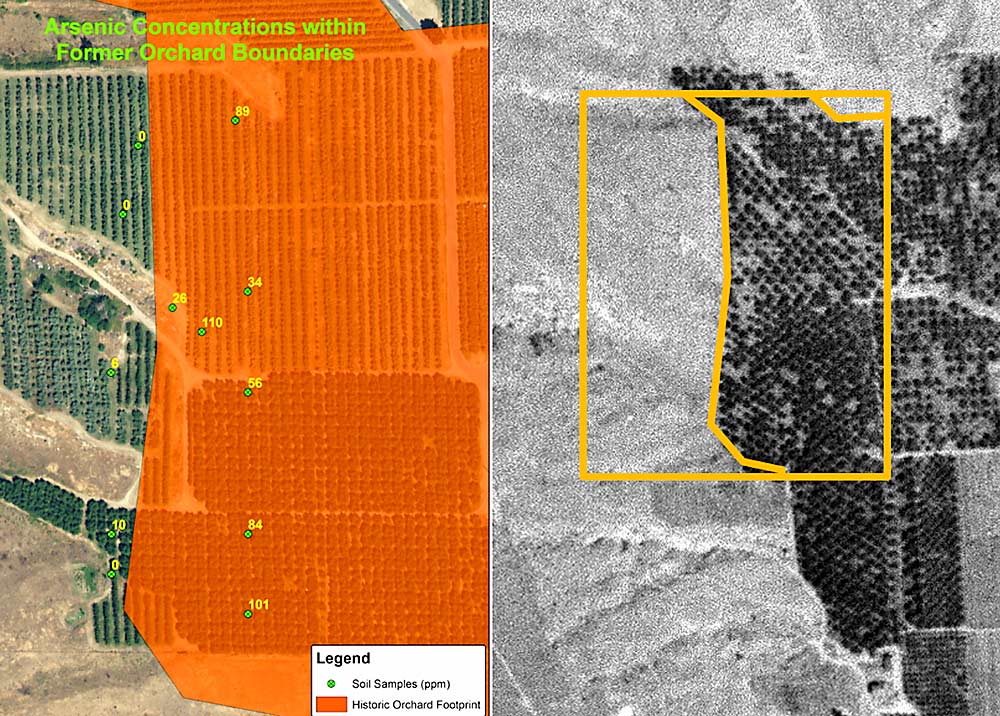

Those considering selling, subdividing or developing in Central Washington should not be surprised if developers ask about lead and arsenic contamination, request soil samples and break out maps more than 50 years old.

Department officials stress they have nothing against orchards, especially the way they are managed today. Lead arsenate, the chemical product that led to the contamination, has been off the table for generations. It was used in orchards all over the nation to control codling moth from 1905 to 1947, after which alternatives such as DDT were discovered. The federal government officially banned lead arsenate in 1988.

But arsenic and lead do not wash away. The toxins remain in soils virtually forever. Starting in the early 2000s, officials at Ecology first targeted schools and parks for cleanup, funding projects at 26 sites throughout Central Washington, home to most of the state’s fruit-growing history.

And it wasn’t just orchards. The chemicals were also used in smelting, leading to extensive cleanup projects in Everett, Tacoma and Northport. The Northport project, in the northeast corner of the state, is managed by the Environmental Protection Agency as a Superfund cleanup.

Other states have launched their own cleanups and have historic pesticide contamination task forces.

Why now?

These days, as housing developments push further into rural areas once covered with orchards, developers and the public have been asking for ways to make sure those properties are safe.

The state has laws that mandate cleanup of soils above certain thresholds. Department of Ecology officials want to uphold those laws without “turning every development into a cleanup site,” said Jim Pendowski, the department’s toxics cleanup program manager, in a blog post about cleanup efforts.

In local environmental reviews, Department of Ecology staff typically made standards recommendations for sampling and buyer notifications. However, they began getting complaints about inconsistent enforcement, Bound said. In September, when they tried to require the sampling under state cleanup laws, they got pushback from property owners and developers.

To create consistency, the agency has formed a legacy pesticide working group to develop a process by which all properties can be sampled for lead and arsenic contamination, efficiently and fairly, Bound said.

Jon DeVaney, president of the Washington State Tree Fruit Association, is a member of the group.

“Ecology has been very clear that this can be managed and mitigated without much difficulty, and is not a cause for alarm,” DeVaney said in an emailed statement to Good Fruit Grower. “It is, however, a potential source of frustration for landowners and developers who thought they understood the standard guidance and find projects or transactions may be delayed.”

Wenatchee fruit grower Laura Mrachek understands the health and environmental concerns but does not want state officials to insist on cleaning up orchards, which have a nonspecific areawide contamination, the same way as a point-source cleanup near an old industrial plant, for example. If they do, they risk creating uncertainty in determining property values for former orchard families trying to sell their land for retirement.

“They don’t have a savings account, their land is it,” said Mrachek, also president of Eurofins-Cascade Analytical, an agricultural laboratory in Wenatchee and Yakima. She’s not a member of the current working group but has been involved with earlier groups dealing with this topic.

Mrachek would rather leave some element of buyer-beware in practice. People who buy houses on former orchard land can then test before they plant a garden or build their kids a playground, or take measures to keep soils at a neutral pH to reduce metal solubility.

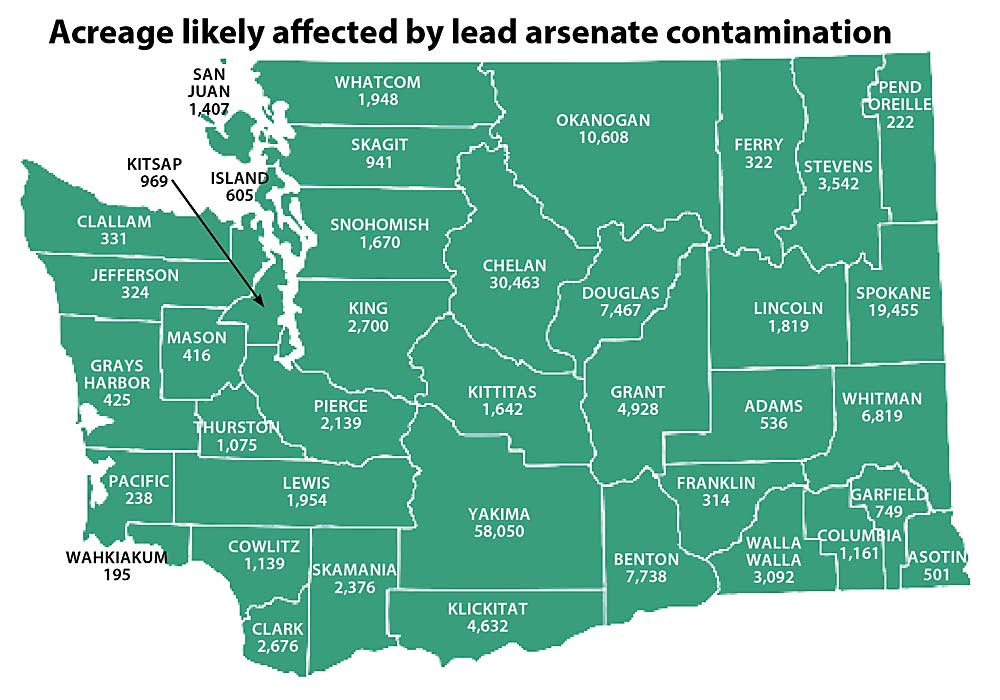

But the state is headed in the other direction: The Department of Ecology has digitized maps of more than 115,000 acres of historic orchards in Central Washington regarded as potentially contaminated. Staff plans to create a webpage by the end of the year, on which anyone in Central Washington can enter an address to find out its lead and arsenic history: Was it an orchard? Was it sampled? Was it cleaned up?

The department also offers free sampling for property owners who want the information for themselves before building. The department would require sampling anyway when development plans are filed.

“We don’t want to stand in the way of (development). We just want to make our expectations known,” Bound said.

—by Ross Courtney

Related:

—Get the lead, and arsenic, out

The question I have is…. how much of this soil does a human have to consume to make them sick?

Fair question. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency says there is no safe level for lead and has set a limit of 0.01 parts per million for arsenic in drinking water. The federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration has set a permissible exposure limit of 10 micrograms of arsenic per cubic meter of workplace air for eight-hour shifts and 40-hour work weeks. Hope that helps some.