Oregon cherry growers will continue to recover from a 2014 freeze by pruning to encourage healthy lower-branch structure in their orchards while balancing their need for fruit development.

“Now it’s just back to managing those canopies,” said Dr. Todd Einhorn, research horticulturist at Oregon State University in Hood River.

Einhorn and Gipp Redman, assistant orchard manager for Gilbert Orchards in Yakima, Washington, led a winter cherry pruning field tour through three cherry orchards near The Dalles, Oregon, in December.

The annual event focused on growers’ continued recovery from a November 2014 cold snap, when temperatures plummeted to as low as 12 degrees below zero, knocking some trees back to the trunks. Steven Renquist, a Douglas County extension scientist with OSU, assisted.

In the wake of the freeze, cherry growers in the areas around The Dalles and Hood River, home to roughly 12,300 of the state’s 15,500 acres of sweet cherries, often had to prune trees back to the snow line to completely restart their trees.

Some farmers harvested more than half their crops even after noticing severe browning on their spurs due to winter damage, Einhorn said.

In spur samples, Einhorn found new xylem and phloem cells at bloom, which helped connect spurs to the rest of the tree, allowing those spurs to support fruit.

Even when half the flowers on a tree die, a grower can still produce a full crop with good fruit set.

Growers may have lost a production year, but with good branch renewal they didn’t have to rip all the trees out and re-establish the block, Einhorn said.

Redman also was pleasantly surprised by the recovery.

“I was once again struck by Mother Nature’s ability to overcome almost total devastation and repair itself,” he later told the Washington State Fruit Commission at its Dec. 16 meeting in Yakima.

Renewal

Today, as growers plan their winter and spring pruning, they find themselves seeking a delicate balance between encouraging fruit this year and promoting overall tree growth for the future in areas where damage was substantial.

Such weather events are unusual for the region, so growers had little history to guide them, and new varieties clouded the picture even more. Thus, a wide array of ideas and suggestions found their way to the table.

“I don’t think there’s a wrong or right answer,” Redman told the group of 60 or 70 growers huddled around Bing, Skeena and Sweetheart trees in varying stages of recovery on the Dec. 15 tour.

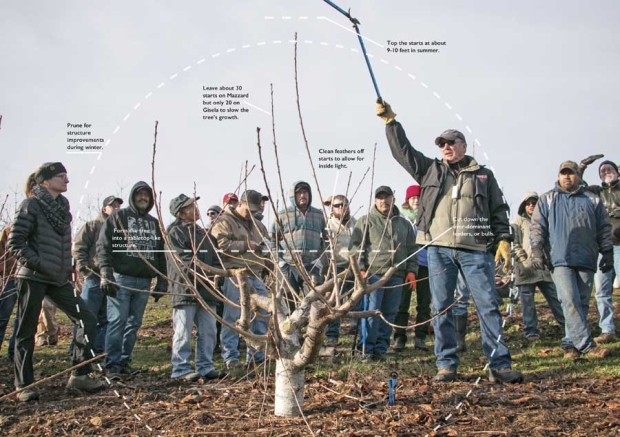

Overall, Redman and Einhorn advised growers to manage excessive vigor in the tops to encourage lower branches to rebuild structure, forcing the tree into a Christmas tree shape to encourage even light penetration throughout the orchard.

Thinning cuts and summer pruning the tops to calm growth are critical to developing the lower canopy for future fruit production.

“We’re trying to grow a tree; we’re not trying to grow fruit,” Redman said.

He suggested growers prune sometime before bloom and in the summer, and train lower laterals horizontally, encouraging earlier fruit production.

A few growers balked at the labor-intensive suggestion of training, including Marcus Morgan, who owns a nearby orchard. “Too much money,” he said.

Einhorn recommended cutting branches in the tops all the way to the leader to avoid leaving stubs that will generate many new shoots and affect canopy light.

Touring orchards

Jorge Cruz of Anderson Fruit cuts the tops out of Bing cherry trees on December 15, 2015, that were damaged by the November 2014 freeze that hit The Dalles, Oregon. The trees were cut down to three leaders following the damage, with plans to prune again this winter and summer to slow the tree’s growth. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

The tour started at Anderson Fruit, one of the more extreme examples of cold damage. The freeze completely killed 5 to 10 percent of Bill Anderson’s trees in his low-lying blocks, while taking the rest out of production for two years.

“At 12 below, nothing stood a chance,” Anderson said.

In response, he pruned aggressively, all the way down to his three leaders, but the trees are regrowing.

Anderson said he planned to prune in the winter and in the summer to slow down growth.

“It’s going to be pretty costly, but you got to do it,” Anderson said.

He plans to harvest 4 to 5 tons per acre of Skeenas in 2017, ramping up to his normal 10 tons per acre in the years following.

Things were not as bad at the next tour stop, a nearby hillside Omeg Family Orchard block where most freeze damage happened below an invisible line slicing across the slope, below which cool air pooled.

Trees above the line lost some spurs but ended up producing fruit at the tops of limbs, Redman said. Below that line trees produced no fruit, prompting the orchard managers to cut all the way to the stubs to restructure.

Redman demonstrated pruning Sweetheart trees, planted in a KGB system, that stood up to his chest.

He cut back a tree to resemble a bush, leaving roughly 20 to 30 similarly sized upward shoots. He also removed some of the thickest, strongest branches, attempting to slow down tall growth and encourage a healthy, fruitful structure lower in the tree.

He recommended 30 growing points on Mazzard rootstock, 20 growing points on Gisela rootstock.

He also demonstrated how to train one of the Sweethearts, previously trained to a KGB canopy, into a steep leader system, something the Omegs were considering in the wake of the damage.

“If you’re going to make a change, this is the perfect time to make a change,” he said.

Sometimes, steep leaders in Sweethearts give growers more control than KGB, Redman said.

Redman also warned that the winter damage might lead to an increase in tree borers, a category of insects that seek out stressed and weakened fruit trees. He had been hearing more reports of borers, so he encouraged farmers to discuss control methods with field representatives early. •

– by Ross Courtney

With pruning a cherry tree for the KGB system, “you raise poles, you don’t raise the branches inside,” says Gipp Redman. “To control the rate of vigor you have to have enough upright leaders. The problem with KGB is we get greedy and don’t make the cuts. You’ve gotta make these cuts to slow the tree down and get the tree thinking about producing fruit.” (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower photo illustration) Click to enlarge.

Leave A Comment