Chad Vargas bought a drone just as an experiment, but he’s using it for all sorts of chores on his Newberg, Oregon, vineyard.

He uses the DJI Phantom 4 quadcopter to measure slopes, scare off birds, monitor bin logistics and string marking ribbon across rows, saving himself the hike.

“I carry it in the truck all the time,” said the viticulturist and vineyard manager for Adelsheim Vineyard.

As for making spray, irrigation and harvest decisions based on aerial imagery — the reason he obtained the unmanned aerial vehicle and a Sequoia multispectral camera in the first place — he’s not so sure.

“I’m skeptical of that myself,” said Vargas, who manages Adelsheim’s 230 acres of estate vineyards in northwest Oregon’s Willamette Valley.

The company is best known for Pinot Noir, Chardonnay and Pinot Gris, but also grows Auxerrois, Pinot Blanc, Arneis and Syrah on a vertical shoot positioning system trellis with 5-foot spacing and 7 feet between rows.

Most of the estate is laid out in small vineyards of about 20 acres each, lending themselves to experimentation with small drones.

The winery bottles 40,000 cases of wine each year, purchasing grapes from off-site. However, Vargas manages only the Adelsheim acreage.

Vargas is known in Oregon for testing and tinkering with new technology. He was one of the first in the area to experiment with thermal, or hot air, treatments on grapes.

Chad Vargas holds his DJI Phantom 4 drone above a color and light registration book to help calibrate the multispectral camera before flying and recording Pinot Noir grapes in Newberg, Oregon. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

He grew up on an Environmental Protection Agency research farm where his father worked and first studied civil engineering before returning to agriculture.

He purchased the drone for himself, but Seattle sensor and analytics company MicaSense issued him the camera to test whether he could use it to guide his decisions about where to pick and when, as well as troubleshoot problems related to fertilizers, irrigation and pests.

His ultimate goal is to use the images taken from the air to measure chlorophyll development, note when it begins to drop off, connect that to a corresponding slowdown in sugar development, determine if his fruit is mature and send pickers out to harvest in specific spots.

Connecting all those dots is a big question mark, he said. “Whether we can get it so good that winemakers will trust this.”

Even large growers have reservations.

Chad Vargas demonstrates his modified DJI Phantom 4 drone that he uses to capture several types of image data of vineyards around Newberg, Oregon. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

“I think that the technology just isn’t there yet,” said Jenn Smithyman, precision agriculture specialist for Ste. Michelle Wine Estates in Prosser, Washington.

So much of drone technology, though exciting and developing rapidly, still is yet to come for tree fruit and wine grapes due to limitations of imagery indexed from multispectral cameras, such as the Sequoia camera and most others currently mounted on drones. Vargas views his drone work as paving the way for that future.

“What I feel like I’m doing is prepping for the next generation of sensors,” he said.

Some in the drone imagery field suggested mixing drone imagery with ground-based methods, such as mounting a camera to a Gator and taking pictures as it drives down the rows.

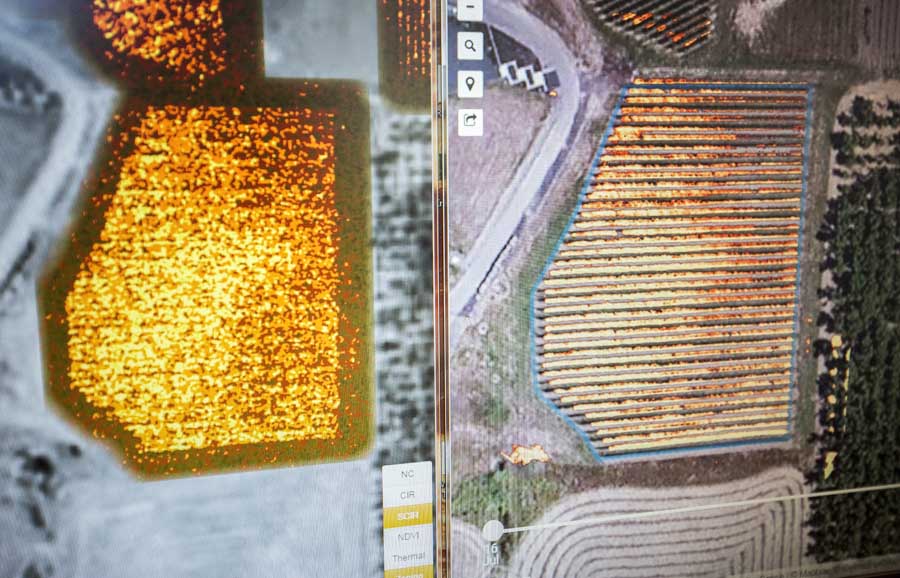

Chad Vargas shows the differences between images captured from a fixed wing aircraft, left, and from his DJI Phantom drone using the MicaSense camera, at right. These images were captured at the same location at the same time period, showing foliage density in the vineyard. Because the drone image data is much higher resolution than a fixed wing aircraft, Vargas says it helps him better manage his vineyards. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

Others suspect more advanced hyperspectral sensors will provide the next step to make drones more useful.

“We need a different sensor,” said Young Kim, CEO of Digital Harvest, a Virginia precision agriculture company, at an August conference in Pendleton, Oregon. “The multispectrum sensor is just too crude.”

Vargas also is testing out the drone to delineate the price points of wine by vine vigor from the air, something he does from fixed-wing aircraft now.

Lower vigor vines tend to produce better fruit, so he uses the aerial imagery from manned planes to find those areas and tell his pickers where to prioritize.

However, the resolution is low. Drone imagery resolution, on the other hand, might allow more specific instructions.

The Phantom runs about $1,500, and the camera about $3,500, he said.

“It pays for itself very quickly when you can go from a $30 bottle to a $65 bottle,” he said. •

– by Ross Courtney, photos by TJ Mullinax

Leave A Comment