Organic apples just might be the sales niche of the future for ambitious Michigan growers. Prices are high, demand is consistent, and a handful of growers are proving that the difficulties of organic orcharding in the region can be overcome. The next step: offering a consistent supply.

Third Leaf Farm and Riveridge Produce Marketing are working on that. Third Leaf, an organic operation near Greenville, Michigan, and Riveridge, the largest apple packer and marketer in the state, recently started pooling their supplies of organic apples to meet demand, Riveridge account manager RJ Simons told visitors from the International Fruit Tree Association earlier this year.

“Spot fills and orders here and there just don’t work,” Simons told IFTA. “We need to build a program.”

Farther east in Flushing, Michigan, longtime organic grower Jim Koan sells organic apples through his on-farm market and to independent retailers. Some years, he sells to processors. Organic apples also supply his farm’s sweet and hard cider or are turned into dried apples.

Koan called the organic market “wide open.” Local consumers want organic apples, and big food companies are taking notice.

“I believe this is the future,” he said.

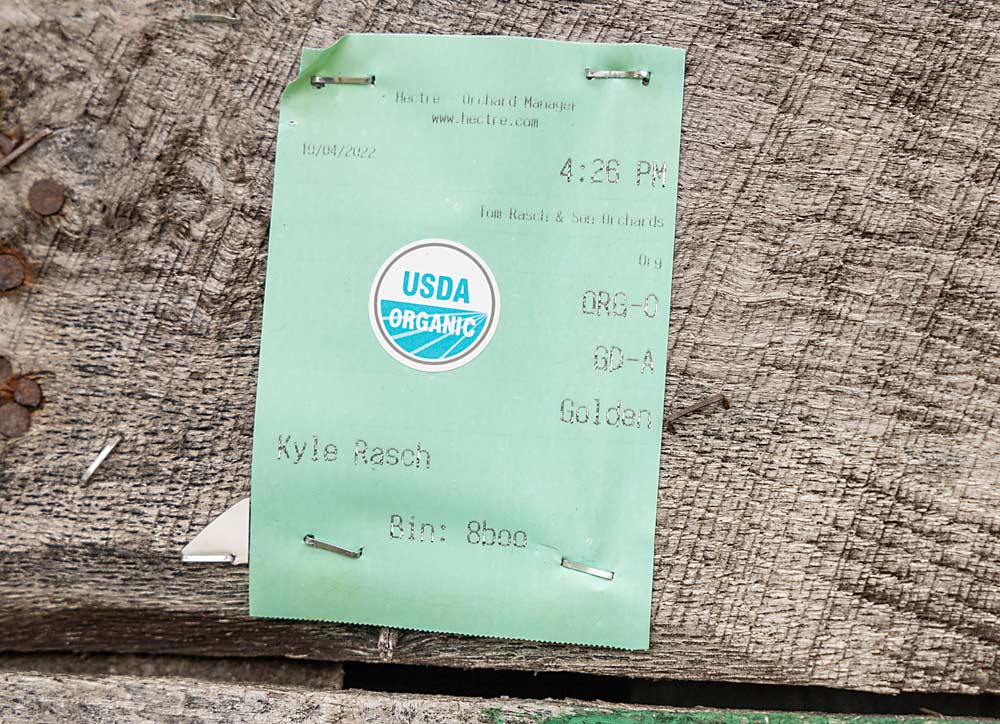

Kyle Rasch sees the same future and is leading his family farm’s transition from conventional to organic — and from Tom Rasch and Son Orchards to Third Leaf Farm. The conversion has been gradual, 10 acres or so a year. Of the farm’s 130 acres of apples, about 30 are certified organic now, with 15 in transition, he said.

Kyle, 31, spent his 20s exploring apple regions in Italy, New Zealand, Australia and India. He would often tag along on an IFTA tour, then stick around for a month or two to study the region’s organic farms. He returned from his travels convinced that he could profitably grow organic apples in Michigan.

Convincing his father and grandfather wasn’t as easy. Kyle was ready to convert the entire farm at once, but they told him to take it one step at a time.

“I’m glad they encouraged me to do that, because we had a lot of failures in the beginning,” Kyle said. “Gradually, we learned that we have to do quite a bit of manipulation and take a more proactive approach.”

Kyle’s dad, Tom Rasch Jr., said he was skeptical at first. He knew growers who tried organic and had given up after a year or two. But if he wanted the family farm to continue, he knew he had to support his son’s passion. By the time their first block was certified, Tom had fully embraced Kyle’s vision. The higher returns on organic apples added to his optimism.

“It’s a completely different way of farming, but I think it’s more enjoyable,” Tom said. “Conventional, to me, is just clockwork because I’ve been doing it so much. I like a new challenge.”

Kyle’s first impulse was to plant new blocks of high-density organic apples, but voles did major damage to the young trees — and there are no organic rodenticides. They now focus on transitioning conventional blocks. If they want to plant new organic blocks in the future, they’ll have to figure out the vole problem. One option is to manage new blocks conventionally for the first year or two, then convert them to organic, Kyle said.

They mound wood chips around young trees to suppress weeds and deter mice and voles, but the amount of chips required is “unimaginable,” he said. They use chicken manure and fish emulsion as fertilizer.

“There’s all sorts of fun organic products we’re still learning about,” Kyle said.

As for disease management, they planted trials of scab-resistant apple varieties. They mostly rely on lime sulfur to manage fire blight, but they haven’t yet had a strike in their organic blocks. They apply many of their organic and integrated pest management practices to their conventional apples, too.

“We’ve almost completely eliminated herbicides across the whole farm,” Kyle said.

Koan, who transitioned his conventional orchard to organic in the 1990s, said it’s best to start as a conventional grower. Mastering the complexities of growing apples should come first, because there isn’t a lot of wiggle room once orchards become certified organic.

With two of his children as partners, Koan now grows about 100 acres of certified organic apples.

One of his reasons for converting was economic. Market pressures were pushing small growers like him out of the apple business.

“The writing was on the wall,” Koan said. “I had to go where there was less competition.”

Another reason was his growing wariness of conventional pesticides. He was already using softer chemistries and “strong IPM” practices by the time he decided to take the organic plunge, he said.

Kyle Rasch said fruit quality and production aren’t quite as high in organic systems, but that can be made up for in price, “where the sky’s the limit.”

The organic processing market appears to be where the money is, at least for now. Last year, organic processing apples fetched five to 10 times the price of conventional processing apples. And organic processing apples don’t have to meet the same quality standards as fresh. Kyle estimated that 10 percent of the Michigan industry could convert to organic and be successful.

“On the processing side, I think organic makes a lot of sense,” he said. “The fresh side really depends on how the markets develop. I would ease into that.”

—by Matt Milkovich

Leave A Comment