If good fences make good neighbors, then workers at Matson Fruit should get along well with their adjacent co-workers.

As apples rolled down the line through May, employees at the Selah, Washington, company sorted and packed while segregated from each other by barriers made of vinyl cold room curtains and shrink-wrap.

They weren’t alone. All over the country, fruit packing houses adjusted to life under the coronavirus by upping cleaning and sanitation practices, taking employee temperatures, erecting outdoor tents for more break room space and other methods as they continued the essential work of shipping apples, pears and cherries.

The adjustments were not easy.

Workers at seven Yakima, Washington-area packing houses walked out over conditions and pay. Shipments of cleaning supplies and masks lingered on back order for weeks. Regulations and guidelines changed so frequently that operators found themselves cross-referencing the bullet points of multiple documents.

Throughout May and into June, Yakima County routinely had the highest coronavirus case rate on the West Coast. More than half of the employees in the agriculture-reliant county were dubbed essential.

Nursing homes, large agricultural employers and community transmission all played their parts, health officials said. And in spite of the response efforts, several packing houses experienced outbreaks, some prompting temporary plant closures.

However, the measures taken by packing houses worked over time, said Lilián Bravo, director of public health partnerships for the Yakima Health District. “For the most part, we’ve definitely seen improvements and they are definitely part of the solution and not a part of the problem,” Bravo said.

As spring progressed, agriculture’s share of cases decreased while the share of community transmissions went up as people relaxed socially over Mother’s Day and Memorial Day, she said.

For the most part, facilities did the best they could both before and after the controversies, sometimes at a high financial cost, said Ray Keller, one of the owners of Apple King, also near Yakima. “A lot of the companies have really stepped up.”

Among the changes at Apple King, supervisors began supervising and timing employees — and visitors — as they washed hands before work and after breaks. “It takes a little longer to get people back to work, but that’s just part of what you got to do,” Keller said.

Due to the sensitivity, many packing firms declined to discuss their changes with the Good Fruit Grower. Five from Washington did — Matson Fruit, Apple King in Naches, Stemilt Growers in Wenatchee, Mount Adams Fruit in Bingen and Columbia Reach Pack in Yakima.

Here’s a list of some of the common upgrades they have made since the pandemic began in early March. Many of them have since become required by state regulators.

—Slowing down lines to reduce employee density.

—Staggering shifts to reduce congestion and allow for extra sanitation.

—Distributing and mandating masks as they became available.

—Temperature checks and symptom inquiries at clock-in.

—Drafting outbreak response plans.

—Reconfiguring indoor traffic flow with designated entry and exit doors and directional floor paint.

—Restricting visitors.

—Inviting inspections from health and safety agencies.

Cleaning and health inspections

Not surprisingly, cleaning practices topped the list of changes. Food safety regulations already require intense sanitation of packing houses, and the coronavirus upped the ante even more.

At Matson, a rotating cadre of employees spend their entire day disinfecting surfaces.

“We have, I don’t know how many people just going around wiping things,” said Jordan Matson of Matson Fruit. Computer keyboards, railings, clipboards and pens all made that list. He even rotated the chores among workers, just in case an obscure surface routinely escaped one employee’s attention.

At Columbia Reach, managers doubled the size of the sanitation crews, rescheduled workdays to allow thorough cleaning between shifts, and lengthened lunch — at company expense — to send in cleaning crews then, too, said Kerri Lovelass, human resources manager. It also gave employees more time to eat, with the facility’s cafeteria closed.

Lovelass had one major piece of advice for other packers: “Develop a relationship and work very closely with the health department.”

With the help of the Washington State Tree Fruit Association, about 20 packers invited staff from the Yakima Health District and, sometimes, the state Department of Labor and Industries to tour the facilities, evaluate measures and make recommendations. Almost all of those companies received follow-up letters telling them they appeared to be complying with guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control.

However, the letters all recommended additional measures the packers could take, such as cleaning in view of employees, offering incentives to follow social distancing and erecting barriers at outdoor picnic tables.

The visits were ongoing in early June.

Columbia Reach went further still, organizing a testing day at the facility with the health district, Lovelass said. Bravo of the Yakima Health District said that option was open to other employers, too.

Makeshift walls and computer software

Temporary barriers between workstations almost took on an art form, as managers channeled their inner MacGyvers to construct ways to prevent employees from sneezing or coughing on each other. Some texted photos of their creations to each other every morning.

Some used plexiglass, but that wasn’t always available. Others hung vinyl cold room curtain from overhead cables or stretched plastic tarps and shrink-wrap across frames erected from PVC pipe for light, easy-to-move walls. After a few days, cleaning crews just threw away the shrink-wrap and replaced it. Still others fashioned partial walls from wood, painted white to make them easier to clean, and hung them between workers on the line or around pear repacking tubs.

Managers also embraced technology.

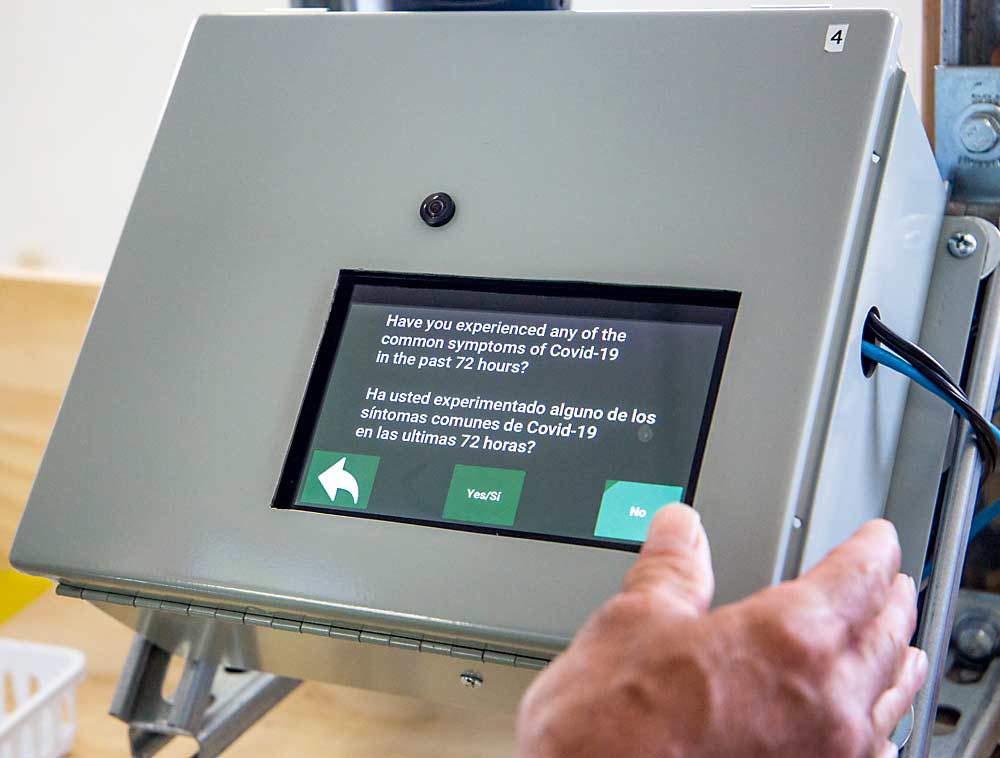

At Matson Fruit, the information technology team wrote programs for the company’s clock-in computer that immediately asked workers about symptoms related to COVID-19, the illness caused by the coronavirus. If the worker answered yes, supervisors, managers and owners automatically received an email.

Exchanging ideas

When it came to drafting response plans, Mount Adams Fruit in Klickitat County, south of Yakima, turned to administrative officer Adam Yoest. Yoest, also a first sergeant with the Washington Army National Guard, took the helm of a company COVID-19 response team charged with adjusting to the rapidly shifting landscape of the health crisis. Drawing from his military background, Yoest drafted decision-tree charts for five different scenarios, a work triage plan and symptom checklists for managers.

The idea, both in the National Guard and at the packing facility, is to remove the pressure of decision-making from the heat of the moment, Yoest said. He also walked supervisors through drills based on those scenarios, such as a worker reporting flu-like symptoms, to avoid allowing complacency, another lesson learned from his National Guard experience.

He calls it all “war-gaming,” and the exercises give comfort to the managers and the workers, he said. “We haven’t had a case yet, but maintaining that level of vigilance … is the most important thing in my mind.”

Many warehouses sought ideas from each other. In early March, Mount Adams officials called friends in Italy.

The company recently built a new packing facility with state-of-the-art food safety and sorting equipment. Officials purchased much of their equipment from Italy, a country hit hard and early by the coronavirus, and they kept in contact with some of their overseas colleagues.

“When they first started hitting their peak, we reached out to see how they were doing, and they told us how they operated,” said Doug Gibson, company vice president. Masks and workstation barriers, commonplace in America now, were among the new ideas at the time.

In the East

When coronavirus-related shutdowns and stay-home orders began in March, some apple packing houses in Michigan and New York state had already stopped packing fruit for the season, and the rest were starting to wind down. Packers set some precautions, such as restricting visitors and taking employee temperatures, but facilities planned to spend the spring and summer developing more detailed safety practices for the 2020 harvest.

New York Apple Sales, which markets apples for nine packing houses throughout the state, planned to spend the summer developing best practices, said Matt Wells, director of field services. Wells and others planned to study changes in the rest of the industry, consulting with facilities and industry groups outside New York state. They are considering requiring masks, surveying employees for symptoms and taking temperatures daily, among other measures, he said.

In Michigan, packing houses developed “contactless” methods to transact business with truck drivers, such as leaving paperwork in the back of the trailer before the truck pulls away, instead of handing it directly to the driver, said Jamie Kober, enhancement director for Riveridge Produce Marketing, which markets apples for nine packing facilities in the state.

When the facilities reopen, they’ll probably institute safety measures such as installing more physical barriers between employees, staggering work shifts and altering the layouts of common areas, he said.

“We’re planning for the worst and hoping for the best,” Kober said. •

—by Ross Courtney and Matt Milkovich

Related:

—Worker worries prompt walkouts

Leave A Comment