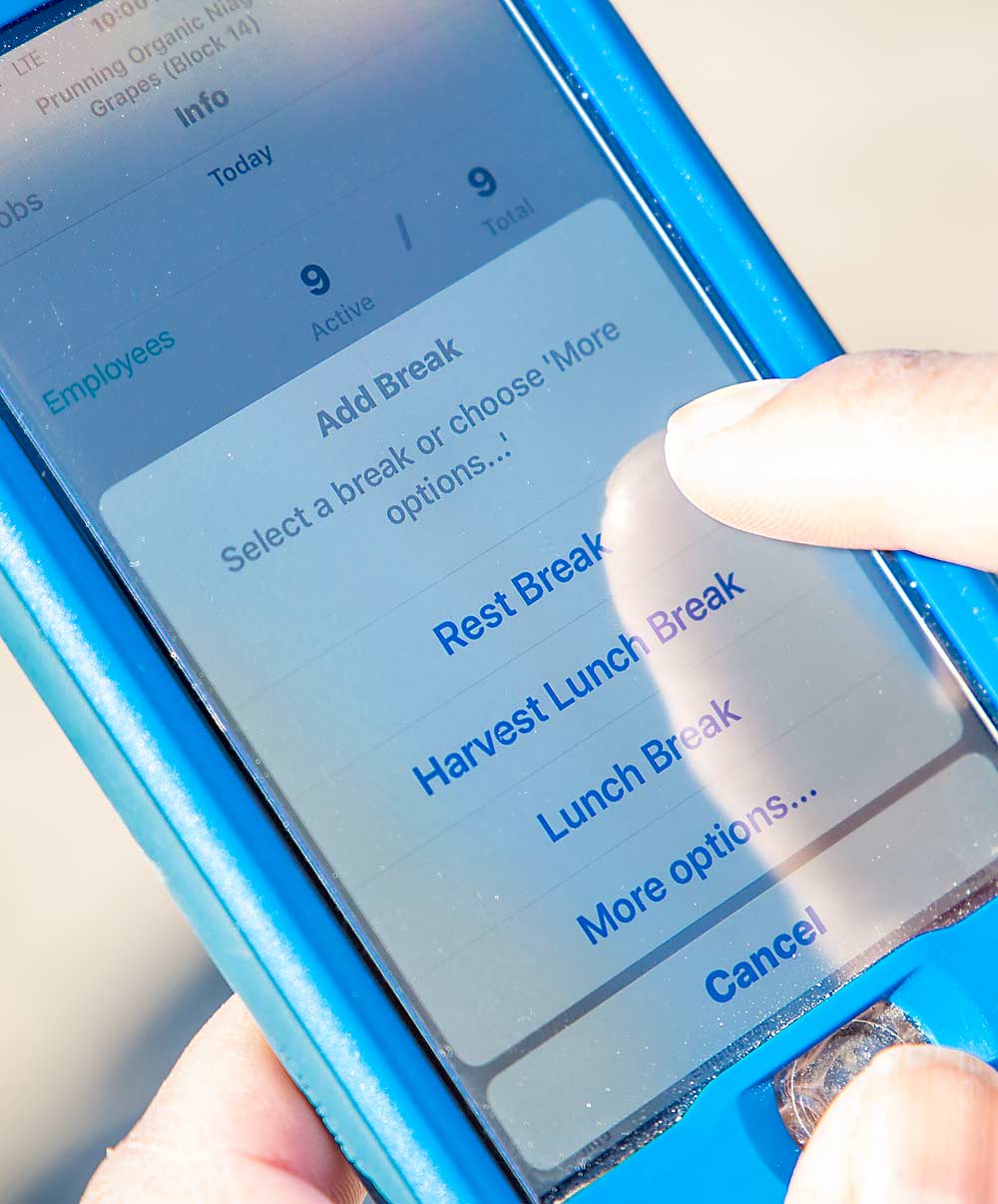

While he checked out new equipment in March, Esteban Ortega’s piece-rate pruners were ready for their rest break in a Concord vineyard a half-mile away. He called up the job on a phone app and punched “Rest Break” at exactly 10 a.m. Immediately, the program began calculating hourly rest break wages.

No more walking around with notebooks. No more double- and triple-checking Excel spreadsheets late in the evening.

“Right here, it’s so easy,” said Ortega, a longtime manager at Lighthouse Farms, a tree fruit and Concord grape producer in Sunnyside, Washington.

Everyone in the fruit industry knows labor costs are rising, and with mandated medical leave, downtime pay and rest break wages, the labor of labor management is turning into its own complex task. Lighthouse Farms and numerous others have switched to cloud-based labor tracking apps to help.

FieldClock of Wenatchee, Washington, PickTrace of Glendale, California, and AgCode of Glenwood, Minnesota, are just a few examples of companies offering such tools, which the industry collectively calls “real-time” labor management.

Here, a few Washington growers weigh in on their experiences.

Introducing new technology

Shelly Durfey worked for a Bellevue, Washington, technology firm before returning to her family’s farm in 2017. On the farm, she found calculating mandated rest break wages for piece-rate employees frustrating. She and her family spent hours at the end of each pay period poring over six different Excel spreadsheets to calculate pay for 160 to 200 employees during peak harvest time.

The company began tinkering with the FieldClock app on a limited basis in February 2018. That spring, Washington also began mandating hourly wages for piece-rate workers’ downtime, in the wake of a state Supreme Court decision.

They started with the hourly employees and added piece-rate workers in time for cherry harvest, Durfey said, when workers replaced their punch cards with QR scans each time they delivered a bucket. As long as the checkers’ phones had cell reception, the information synced to the computer in Durfey’s office, where she could tell within an hour if something was wrong, such as a picker moving too slowly.

The pickers began trusting the system more as time went on, Ortega said. By the end of the season, they often paused and looked up inquisitively if they didn’t hear the “beep” from the QR scan when delivering a bucket.

The entire business hooked up in 2019. The farm’s managers and most of the workers carry the app on their phones, which they use with a QR code on their badges.

For example, in the shop, a worker who just finished repairing a tractor’s flat tire and wants to shift to changing the oil on a truck would scan the QR code. The system would automatically track the time spent on each job, accurately logging the cost of the work for Durfey and her family when they draft budgets. Meanwhile, roaming workers can stay on the clock if they stop on the way home for auto parts or office supplies, logging out remotely when they complete the errand.

Durfey also uses the program to track costs per acre within each block. The company introduced a similar app for fuel management, and she is shopping for one that will track equipment, products and spray records.

Other growers

Joe Britton, operations manager of Teeny Farms in Chelan, Washington, previously managed an automotive repair facility before joining his wife’s family’s orchard, which, at the time, was filling out time sheets by hand, tracking harvest with bin tickets and punch cards and merging the information into spreadsheets.

“It was pretty cumbersome,” he said. “There was not a lot of accountability and there were a lot of errors, which would require a lot of re-entry and extra work.”

The company switched to FieldClock “cold turkey” in 2018. The owners were easy to convince, but workers pushed back, as they sometimes forgot to log in or out and didn’t trust their hourly reports. To ease their concerns, Britton set up a wage dispute system and thoroughly listened to every complaint, sometimes agreeing with the workers and paying the difference. Over time, the workers bought in.

“It took a lot of persistence,” he said.

By the time the next harvest rolled around, employees were used to it. Some new applicants showed up with their own badges from previous workplaces. The badges don’t work that way, but it proved word had been getting around.

Britton thinks small growers with later sites still have time this year to set it up for cherry harvest.

Gilbert Orchards switched its labor management to PickTrace early in 2019 and used it for cherry, pear and apple harvests. The program also relies on phones to scan bar codes on employee badges and bins.

Previously, the Yakima company used paper timecards, which took more time for foremen to fill out and afforded less detail when tracking costs block by block, said Dan Keller, orchard manager.

Keller would not recommend growers of any substantial size try to make the change in time for cherry harvest this year. The technology required a lot of setup and a learning curve.

However, his crews adjusted more quickly than he suspected, especially his veteran employees. That gives him encouragement for adopting new technologies in the future.

“I was concerned those guys would get frustrated and give up on it, but that just hasn’t been the case,” he said.

—by Ross Courtney

Related:

—Working day to data in the orchard

Leave A Comment