Kate Evans shows one of the program’s new seedlings and a page from the cross breeding “cull” sheets she and her staff use when moving plant material through the Washington State University pome fruit breeding system in Wenatchee, Washington, on Monday, April 23, 2018. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

Breeding fruit poses a monumental logistical challenge.

The plant material, traits and data points of 600 crosses and 300,000 seeds must be counted, labeled, indexed and not only stored accurately, but in a way that’s easy to find.

“One of the biggest challenges in a breeding program is just keeping track of your material,” said Kate Evans, the Washington State University apple breeder who oversees the program that released the much-hyped Cosmic Crisp.

Just take a look at her greenhouse. Tiny green seedlings stretch on tables the length of a basketball court, and that’s just from one year. More grow elsewhere at the university’s research stations and commercial trial blocks throughout the state, either making their way through a breeding journey that lasts 20 years, or waiting on standby to be used as parents.

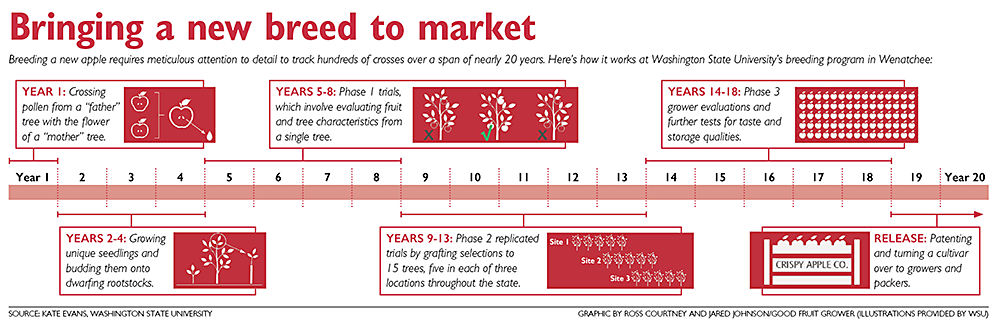

The breeding process all starts with the spring cross, gathering flowers in Ziploc bags from “father” trees, collecting their pollen and applying it with the eraser of a pencil to the stigma of “mother” trees — over and over again, row by row, tree by tree.

The hunt for new varieties continues, as research technician Bonnie Schonberg uses a pencil eraser to apply pollen to the stamens of an unnamed variety at the university’s Sunrise research orchard near Wenatchee. Schonberg previously stripped and emasculated the blooms to isolate the cross pollination. (Ross Courtney/Good Fruit Grower)

The seeds sprout in tiny pots made of irrigation pipe segments and spend the first year in the greenhouse slotted in racks of 96 because that’s how many the university’s DNA laboratory analyzes at a time. A staff member’s friend constructed them of plastic mesh especially for the breeding program.

Evans compresses the reams of data into a simple map with green or red for each rack — green for keep, red for cull. The culls are either thrown away or donated as bug food for an entomology project. Their DNA simply did not have the genetic markers of the traits the breeding program seeks.

In spite of technology, it’s all a rough guess. Evans cannot know for sure if she discards an absolute gem, the apple that would redefine apples.

“There’s never really a wow moment,” Evans said. It’s just a huge process of elimination, she said, though she prefers the term “selection.”

The seedlings that make the cut are nurtured at Willow Drive Nursery in nearby Ephrata, then grafted onto Malling 9 rootstocks in an orchard, usually Columbia View, a plot overlooking the Columbia River about 15 miles north of Wenatchee to mature for about three or four years.

Only then do they enter phase one selection based on their growth habits and fruit production. That lasts for about another three or four years. The favorable samples advance to phase two, replicated to 15 trees at three trial sites. Over the winter, Evans predicted 10 new selections would be planted for phase two this year.

Phase three gets serious, with grower evaluations, taste surveys, focus groups and storage tests. The grower-funded Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission, which funds some of the breeding program’s work, has partnered with the university to manage those phase three trials.

The whole process takes as long as 20 years. (See graphic.)

Meanwhile, Evans keeps many of those crosses passed over in earlier phases, using them as parents for new crosses, meaning her program will continually grow. Her goal is to keep the 20-year pipeline full, so new varieties are always on the way. She does not believe any single apple, even a good one, will prop up Washington’s apple industry by itself.

So far, the university has two cultivars, known as L and M, in phase three. They are crosses of Cripps Pink and Honeycrisp, planted in commercial trials in Quincy. Evans and her team still use variety numbers internally but began publicly identifying their samples with letters to protect patent and trademark odds down the road. They predate Evans, who started in 2008.

Both varieties are tart, crisp and juicy and typically generate excitement when the university passes the apples out with survey forms at trade shows and conferences. Still, their future is far from certain. “There’s no guarantee that either of them will make it,” Evans said.

But if she has her way, there will be more new apples right behind them. •

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment