Oregon State University agricultural economist Clark Seavert, pictured in a high-density pear trial block at Hood River, Oregon, says most growers are playing not to lose, rather than playing to win. (Geraldine Warner/Good Fruit Grower)

The three key aspects for successful orchard renewal are still price, yield, and cost, but the winning strategy is to focus on increasing revenue, rather than minimizing costs, says Oregon State University agricultural economist Clark Seavert.

Innovation is one way growers can remain competitive, Seavert said during the Washington State Horticultural Association’s annual meeting. “How you incorporate innovation into your business and business strategies will determine how profitable you will be in the future.”

Three strategies

Seavert identified three business strategies:

Play to win: People who play to win are the innovators and early adopters of innovation. This is a high-risk strategy that can also generate high rewards. These people choose a segment of their supply chain in their business where innovation can provide them with a competitive advantage. This may be profitability, increased efficiencies, or reduced inputs.

Play not to lose: The majority of growers fit into this category. They take opportunities or adopt new technology when available. It’s not always possible to play-to-win because it’s too risky. These growers might also be concentrating on a play-to-win strategy with a particular segment of their business that requires too much management time or financial resources. Therefore, they may concentrate on other aspects of their business after certain play-to-win strategies succeed.

Simply not playing: These growers are slow to innovate and follow a long way behind.

Focus on returns

To demonstrate the importance of focusing on increasing returns rather than reducing costs, Seavert cited a study on the costs of producing Gala apples compiled by Washington State University agricultural economists.

In the hypothetical 40-acre mature Gala block studied, 70 percent of the fruit packed out Washington Extra Fancy Premium, with 10 percent Washington Extra Fancy, 8 percent Washington Extra Fancy No. 2, and 12 percent culls. Fruit peaked on sizes 80 and 88.

The total cash costs to produce a crop of 50 bins per acre of Gala apples in Washington State are $6,377 per acre.

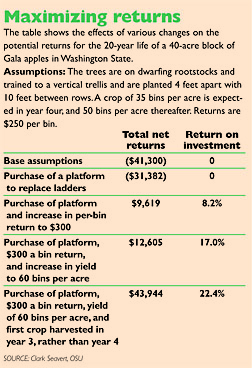

The study assumed that workers used ladders and the block would come into production in year four with a crop of 35 bins per acre and then would produce 50 bins per acre annually. The return was assumed to be $250 per bin. Based on the assumptions in the study, accumulated losses over the life of the orchard amounted to $41,300 per acre, assuming a 3 percent annual inflation rate.

Seavert looked at the impact of minimizing costs. Decreasing fertilizer costs by 10 percent reduced costs by only $13 per acre. Reducing labor for pruning by 10 percent cut costs by $78 per acre. Decreasing cullage from 12 to 10.2 percent reduced costs by $207.

Maximizing revenues had much greater impact. Increasing the percentage of top grade apples by 10 percent generated an additional $295, while shifting 10 percent more fruit into the size 88 and larger categories generated additional returns of $692 per acre.

Platform

Seavert then looked at the financial impact of innovations in the same hypothetical Gala block for a 20-year period starting at planting. Purchasing a $35,000 platform in order to reduce pruning and thinning labor costs by 30 percent resulted in accumulated losses of $31,382 per acre over the life of the orchard, versus $41,300 in losses when ladders were used.

Purchasing the platform and growing target fruit with a return of $300 a bin resulted in total net returns of $9,619 per acre, an 8.2 percent return on investment.

Purchasing the platform, growing target fruit, and increasing yields from 50 to 60 bins per acre resulted in total net returns of $36,654 per acre, a 17 percent return on investment.

The study assumed that the trees would produce their first crop in year four. Shifting the first crop one year earlier resulted in total net returns of $43,944 per acre, for a 22.4 percent return on investment.

Seavert said free software is available to help growers analyze the economic impacts of adopting innovations or making changes at the orchard.

AgProfit can answer the questions, “Can I make money doing this?” and “Can I afford it based on a block analysis?” The program shows the cash flow and inflates costs and revenues over the 20-year life of the orchard.

AgLease can be used to establish equitable crop-share and cash-rent leases.

AgFinance, which is still being developed, will help answer such questions as, “If I plant a new orchard or implement the new technology, can I afford to do it on a whole-farm basis?” It will allow growers to look at returns and prices over time and see how different blocks are performing. This software should be available within the next few months, Seavert said.

I numan is Özver agricultural engineer turkey niğde: pear seedling root zone made in the image on a web page that you have mulch material (nylon) What are the benefits of irrigation and materials from the other direction. I want to learn.