Despite growing recognition that the wild bees buzzing around their orchards provide pollination services, many Northeastern apple growers continue renting honeybee hives as an insurance policy.

But with increased cost and shrinking availability as beekeepers struggle, forgoing honeybees looks increasingly appealing and more and more growers have decided to go without.

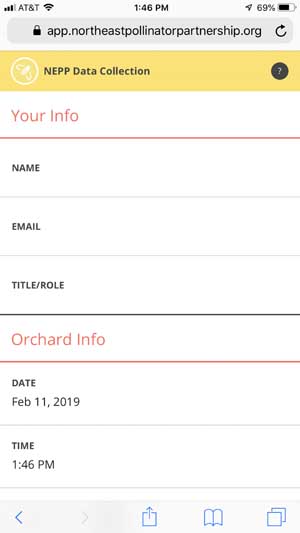

To help growers make good risk management decisions when it comes to pollination, researchers at Cornell University designed an app to help New York growers assess the abundance of native bees in their orchards.

Known as the Northeast Pollinator Partnership, the program helps growers learn to spot native bees and, by counting bee abundance during bloom for just five minutes, three times, predicts if wild pollinator populations are sufficient.

“We have growers calling every year that they can’t find anyone to rent hives from,” said Maria van Dyke, outreach coordinator for the Northeast Pollinator Partnership.

“The app was created so that the grower can take the information to say, ‘I don’t have that many wild bees, so I depend heavily on honeybees. So, I know I need to keep these relationships with my beekeepers really strong,’” she said. “Or, if you find out that you have a lot of wild bees, you are getting most of your pollination from them, then you don’t have to rely on hives.”

The app is the result of years of research showing that many solitary wild bees are more effective pollinators than honeybees and that there’s a direct relationship between bee abundance and seed set, a fruit quality factor researchers use to assess sufficient pollination, van Dyke said.

Ten years of research demonstrates that more natural habit around orchards means more wild bees, and more wild bees mean more pollination.

The app sounds like a good idea, but growers using it should be mindful of the important “edge effect” when it comes to native pollinators, said Pennsylvania State University entomologist David Biddinger, who has been studying the benefits of wild bees for years.

“There’s a definite edge effect. Honeybees will go far and wide but wild bees don’t nest in the orchard, due to pesticides, so they fly in from the edges,” he said. “You can get a pollination deficit in the middle of a 20-acre block.”

For small orchards surrounded by woods in hilly Adams County, Pennsylvania, that’s rarely a problem, but one which growers with larger blocks should be mindful of. Biddinger recommended growers with large blocks stock a few honeybee hives in the center, rather than on the edges, as is common practice.

[/fusion_builder_column]

A recent review of apple growers in New York and Pennsylvania found that only about half now rent honeybees for pollination, and the likelihood of renting hives is directly related to farm size.

Wild bees are better adapted to local weather, fly during cooler temperatures than do honeybees, move more quickly around orchards and have more body hair that delivers pollen from flower to flower, Biddinger said. “I like to call wild bees pollen bees, because that’s really what they are after.”

Better pest management strategies that protect bees from insecticides and protect the natural habitat around orchards where they live have made it easier for native bees to return to work in modern orchards as well.

The app is free, and it’s been available to New York growers for a few years now.

While dozens of growers are using it, it hasn’t yet been embraced as broadly as the researchers hoped, van Dyke said. They are hoping to expand outreach and testing of the app in other locations, with additional funding in the future.

“The biggest thing is just getting what we know out there to the grower public,” she said. “Having the app is a way to get us out to talk about the issue with people and give them some ideas.”

Using the app only requires an understanding of the difference between honeybees and other bees; growers don’t actually have to identify the wild bees. Counting at least seven wild bees visiting a flower in a 1 meter-square area of observation means there is sufficient native pollinator activity, van Dyke said.

“In these days when all these things are affecting honeybees, it’s nice for these growers to know that they can fall back on these wild bees,” she said. •

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment